London Art Fair

1883 magazineReview

2014

A review of the annual art fair, for 1883 magazine

I find it slightly confusing that “art” can still be so separated from “photography”, that galleries can advertise themselves as showing “fine art and photography” as if their Venn circles didn’t cross. In an age where everyone carries with them a powerful camera in their pocket, and when our very identity is formed from the socially mediated visual presentation of ourselves we project into the outside world it’s slightly odd to consider “photography” as a thing apart from regular art practice.

This is in part due to historic categories and the distance between industrial mechanisms from those of traditional fine art, but also to some extent because of the photographic world protects itself from becoming subsumed within the artworld and losing its own identity and visual language it has forged over the last century and a half.

But it’s also futile. Just as the democratisation and affordability of photographic processes has effected the social landscape it has also hugely informed art practices from all disciplines. Artists are as likely to use a photographic image or video in their practice as any other more traditional medium, but more importantly graduates of photographic courses frequently put down the camera to explore other methodologies or to augment and work with photographic imagery more akin to an “artist” than a “photographer”.

And so I came to London Art Fair with a curious interest in relationship between it and Photo 50 which is both a part of it but also tucked away two floors from the main action. Just as galleries that say they show “fine art and photography” seem to cling to an outdated understanding of both forms it seems odd and slightly patronising to pretend the two exist in distinct arenas.

Photo 50 is a guest-curated exhibition of contemporary photography and this year’s exhibition was titled Feminine masculine for which the curator, Federica Chioccetti, inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s 1966 film Masculin Féminin, lookedto “explore the challenge of representing the mysterious, at times ineffable and immaterial, dynamics that occur or do not occur between a woman and a man”.

What was curated was a mixed bag with moments of interest but a general feeling of a mediocre graduate show which ticked all the boxes of presentational methods but nothing which surprised or had enough grit to wow in an artistic sense.

“Happy Together No.1”, 2010, by Francesca Catastini

Natasha Caruana’s works from the series “The Married Men” and “The Other Woman” started interestingly. A man’s arms resting on a table alongside a receipt and cash to record – the artist had used disposable cameras to record non-identifiable details from men she had met, for the purposes of the project, on websites for extra-marital affairs. She also recorded them talking about their reasons and desires and this image was crying out to be accompanied by captions or sound from that conversation. But, instead, alongside were two photographs from a parallel project where cheated-upon women posed in their homes, concealed within domestic settings. Too predictable and safe in comparison to the first piece which had more roughage and intrigue.

The rest of Photo 50 carried on in much the same vein, with an overriding feeling of traditional, white and heterosexual perceptions of relationships largely concentrating on physicality rather than anything profoundly emotional or tangential. Elinor Carucci’s series of ‘intimate’ photos of her with her husband felt too staged to offer insight into any other personal condition than ego and Martin Crawl’s “Puritan Porn” reproduced images from a 1930s book entitled “Handbook of Physical Culture for the Marriage” disappointed because of unfulfilled potential - as an exercise in facsimile it was superbly executed, as an artistic act it left me frustrated.

“Egg Shell pink set” from the series Empty Porn Sets, 2010, by Jo Broughton

Jo Broughton’s “Empty Porn Sets” presented the visual language of a sex industry created largely for the male gaze, but empty and without the performers. So we see a pink boudoir, schoolroom and hospital, but framed to indicate the artifice and construct of both the physical space as well as the psychosexual one within the minds of any distanced viewer. The strongest work in Photo 50 it still felt a bit like it was desperately clinging onto an idea of art-photo-journalism rather than engage artistically.

So I set off downstairs to the main exhibition space of London Art Fair in search of works which satisfied more in exploring that contested territory between photography and artwork.

“IMPERMANENCE_UNTITLED_DAVIDHYUN”, 2013, by Seung-Hwan Oh

Seung-Huan Oh presented two large portraits produced from a decayed negative. The artist had allowed an organic process to eat away at the neg before capturing the image at a desired point – a reminder of natural processes at play in life, memory, representation and photographic processes. The end results are portraits literally eaten into by an oil-slick like breaking down of the perfect image is alluring.

“A Fall of Ordinariness and Light”, 2014, by Jessie Brennan

Jessie Brennan’s immaculate drawings also beautifully played with photography. A series of works representing Robin Hood Gardens - the Smithson’s social housing masterpiece currently on death row and awaiting execution – during various stages of collapse. But the decline was purely within the renderings – her immaculate drawings recording stages of crumpling the source deadpan architectural portraits. There are many layers within: the flatness of the drawing capturing the depth of screwed up photographs, which are themselves flat representations of the physical entity which, in turn, is considered more as an icon for an architectural style than as home to many hundreds of individuals.

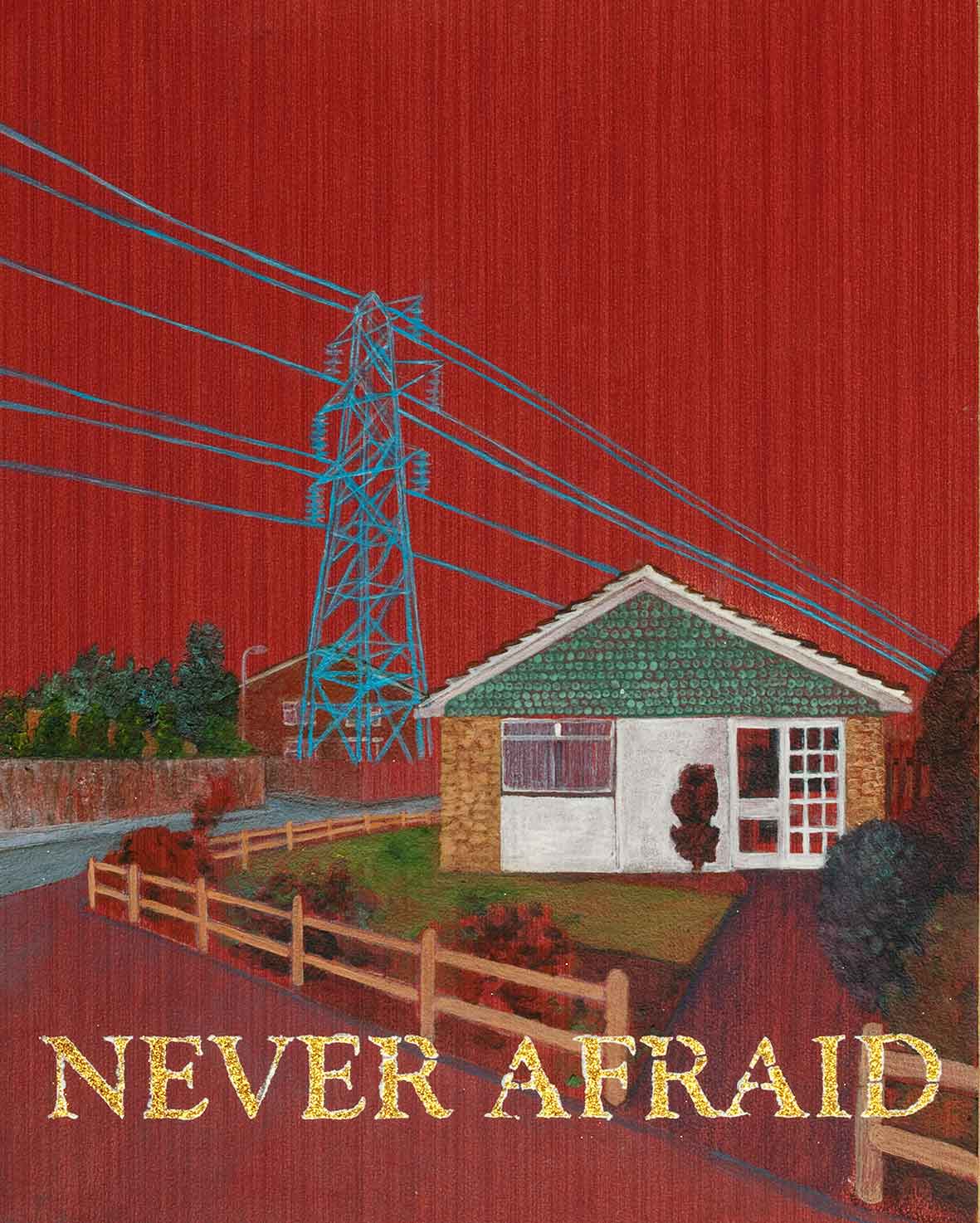

“Roman Way”, 2010, by Sarah Sparkes

That sense of home, and re-representation of the photographic capturing of it, is also considered in Sarah Sparkes’ series. Revisiting houses from her childhood to photograph the suburban experience she then recreated those photographs, drawing in block colour onto wallpaper she had taken from each house as a girl - as if knowing one day she’d want to use it as the to consider those slightly ‘other’ landscapes of suburbia and childhood.

“Restore to Factory Settings”, 2014, by Felicity Hammond

Remembered landscapes also fed into Felicity Hammond’s “Restore to Factory Settings”, a digital montage of 20th century industrial landscapes, including former worksites of family members. A blue tinge spread across the whole image, at once reminding of the digital blue screen of death as much as a cyanotype aesthetic of the medium’s past. A sense of melancholy across it all, the image at once aesthetically composed but its totality as decay, mess and detritus.

“Sangenes Sang”, 2015, by Katsutoshi Yuasa

Katsutoshi Yuasa presented a panoramic pastoral, romantic lakeside setting where trees were both the subject and, being a woodcut, the constructive element of the image. What results is a work which only comes into focus when standing a couple of metres away, the closer you get the more fragmented and illegible the image becomes. But that an image so delicate could be reinterpreted from an everyday camera’s ‘snapshot’ is a fascinating transformation.

There were other works dotted around the fair which either used the camera as a tool or more intelligently considered what photography is within a widened notion of the art-world where it’s OK to exchange media and ideas between different processes. Sure, there were too many drawing over/stitching into archive portraits and there meaningless largeformat-but-digital images of third world empty urban landscapes (clickbait for the mid-level artbuying market) but other works stood out, notably Maria Rivais’ collages which, while not packed with new artistic ideas, were humourous and reflective upon the physical and psychological landscapes represented.

“Untitled”, 2015, by Marcus Harvey

But the most interesting work in this quest for a photographic/art hybrid came from Marcus Harvey. Harvey is an established painter who not only has a developed and widely exhibited practice, but also runs a magazine, art school and gallery. His work is predominantly rooted in painting, but for a new seriesInselaffe, which will be exhibited in an exhibition at Jerwood Gallery in Hastings this summer, he paints directly onto collaged fragments of seascapes and skyscapes. In an artist talk he described “using photographs like found objects in sculpture”, and the way in which the deeply worked paint of the monochromatic iceberg-like islands float on both the photographic backdrop as much as the sea they sit on leaves a great impression.

Reminiscent of Hashima Island, a derelict dystopia inhabited more by film crews like that of James Bond than it ever is by people, the floating island fragments (Inselaffeis a German word meaning “Island Monkeys”) could equally be extracted fragments of the White Cliffs of Dover set adrift like icebergs, left to slowly melt their identity and structure into a subsuming sea which both supports and removes. A politically charged series (accompanied by brass sculptures, including one called “Maggie Island”, using elements of British identity from Thomas the Tank Engine, Hitler, cabbages and fragmented doric columns) it is more observational than dictatorial, but through that message all the more powerful.

And the fact that it sits upon a photographic canvas, so the painterly element sits proud of the flatness behind, that there is together a symbiosis between digital and analogue, printed image and that constructed with paint, only makes it richer and more apposite for the age Britain finds itself. It is also a far healthier positioning of the role of photography in the artworld than that of sectioning itself off in a visual protectionist language, upstairs in a different room and away from the larger conversation.