Jean-Michel Jarman: The Last of Docklands

Repeater BooksChapter

2018

An essay on Jean Michel Jarre’s 1988 spectacle concert in the London Docklands, written as a chapter to Regeneration Songs: Sounds of Investment and Loss from East London, on Repeater Books, information HERE.

Distinct edited versions of this text appeared in The Quietus, HERE, and also on the Repeater Books blog, HERE.

Distinct edited versions of this text appeared in The Quietus, HERE, and also on the Repeater Books blog, HERE.

Millennium Mills, 2018. ©The author, 2018.

Silvertown is a new piece of city in

London’s Royal Docks for people to make, show and share. Silvertown

is an effect. Buildings reinvented. Spaces activated. And openness,

wellness, curiosity, collision and collaboration are the order of the

day.

– Silvertown developers, 20171

– Silvertown developers, 20171

A great hulk of industry stands proud in the Royal Docks, a solid white monolith which seems to relish looking across at the flimsily engineered frame of ExCel Arena across the water. This is old Docklands staring at the new, an apparent solidity and sheer mass of industry looking down upon the young interloper’s service and entertainments economy.

Millennium Mills, 2013. ©Bradley Garrett,

The

1930s Millennium Mills have hung on, surviving the closure of the

Royal Docks in 1981 and grand renovation plans including an early

2000s scheme to fill the building with luxury apartments, with an

aquarium and extreme sports centre next-door for what Ken Livingstone

said would become “an international visitor attraction worthy of

Europe’s world class city”.2 The

2008 financial crisis killed the plans, with Millennium Mills

remaining empty for urban explorers and ruin-lustful photographers.3

To coincide with the 2012 Olympics, empty tracts at its base were transformed into the London Pleasure Gardens, a popup modern-day interpretation of the Vauxhall Gardens. One week in, it hosted a star-studded music festival, Bloc 2012, for musicians including Steve Reich, Snoop Dogg, and Orbital. Snoop never got on stage; the festival cancelled in chaos and overcrowding before his slot.4

The site was planned to become a temporary “meanwhile space” for arts, entertainment, and activity, putting the site on the cultural map whilst developers got their plans and finances lined up. The rear of Millennium Mills would be a backdrop for video mapping projectors; a ten-storey-high Shepard Fairey mural was already painted over a façade. It had even received a loan of £3 million from Newham Council to transform the rubbish-hewn site, but debris and dust remained throughout, concerning locals aware of historic asbestos.5 Vauxhall Gardens lasted two centuries until swallowed by industrial expansion in 1859; the Pleasure Gardens closed five weeks into an intended two years, going into administration, workers and bills unpaid.

To coincide with the 2012 Olympics, empty tracts at its base were transformed into the London Pleasure Gardens, a popup modern-day interpretation of the Vauxhall Gardens. One week in, it hosted a star-studded music festival, Bloc 2012, for musicians including Steve Reich, Snoop Dogg, and Orbital. Snoop never got on stage; the festival cancelled in chaos and overcrowding before his slot.4

The site was planned to become a temporary “meanwhile space” for arts, entertainment, and activity, putting the site on the cultural map whilst developers got their plans and finances lined up. The rear of Millennium Mills would be a backdrop for video mapping projectors; a ten-storey-high Shepard Fairey mural was already painted over a façade. It had even received a loan of £3 million from Newham Council to transform the rubbish-hewn site, but debris and dust remained throughout, concerning locals aware of historic asbestos.5 Vauxhall Gardens lasted two centuries until swallowed by industrial expansion in 1859; the Pleasure Gardens closed five weeks into an intended two years, going into administration, workers and bills unpaid.

That art, culture, and music are used to rebrand and market a site or project is now an expected element of any major development. Phrases like “placemaking”, “meanwhile”, “pop-up”, and “cultural capital” are now as embedded within emerging-artist lexicon as much as with the agencies and quangos constructing, marketing, and selling real estate. The latest scheme for the site will see Millennium Mills become a “making, showing and sharing community” of creatives, sitting within the wider Silvertown regeneration area, the idea of culture deeply embedded into a £3.5billion pitch already dubbed by GQ as “the new Brooklyn”.

The largest asbestos removal in British history has cleared the site and, despite a brief pause in works when sparks from steel-burning workers ignited a fire across two floors, the mill is being “reinvented” as a space of entertainment and cultural industry. The construction site is occasionally interrupted by cultural placemaking events in preparation – a dance performance with “interactive audio experience” took place in the remains of London Pleasure Gardens and a nearby industrial building which will become shared workspaces launched with a “warehouse-warming” rave and “immersive” contemporary art exhibition coinciding with Frieze art fair.

Derek Jarman, still from The Last of

England, 1987. London: Second Sight Films, 2008, DVD.

Derek Jarman, still from The Last of

England, 1987. London: Second Sight Films, 2008, DVD.The rain pours down; skinheads beat people

up; there are race riots; there are drug fixes in squalid corners:

there is much explicit sex, a surprising amount of it homosexual and

sadistic; greed and violence abound; there is grim concrete and much

footage of “urban decay”.

– Norman Stone in The Sunday Times, 19886

– Norman Stone in The Sunday Times, 19886

Derek Jarman’s film The Last of England took its name from Ford Maddox Brown’s oil painting of middle-class emigrants reduced to poverty, on a boat with their backs to Dover’s White Cliffs, destined for Australia and a new beginning. Jarman’s film ends with refugees earlier seen huddled and nervous under military watch on the dockside next to Millennium Mills, crowded into a small boat floating off, drifting westwards along the Thames. “Are they leaving for a new life; or are they going to their deaths?”7 he asks. The boat calmly rows into unknown darkness.

The ninety preceding minutes are a schizophrenic and mesmerising montage of debauchery, history, personal archive, and poetic montage. “I don’t work for a passive audience, I want an active audience”, Jarman says, and the work he created, the culmination of a decade looking at the physical and psychic post-war state, demands an attentive eye and open mind. A poetic rendition of the rise and fall of post-war postindustry, where “the present dreams the past future”,8 the Royal Docks and Millennium Mills are locations through to the final scene of Tilda Swinton manically ripping off a wedding dress, spinning possessed in front of a dockside bonfire.

Starting with footage of Jarman himself writing at a desk and mixing family footage shot by his father, there is also a strong autobiographical element to the film in which a romantic trace of middle-class, pastoral memory lingers amongst ashes of Seventies and Eighties London flames. His father would later turn “potty”,9 trauma from World War II bombing raids he carried out which caused so many civilian casualties in the path of military progress.

Representations of ruinous London, coupled with scenes of heroin use and the British flag flailing beneath a balaclava’d soldier writhing with a naked male, raised the ire of Conservative traditionalists. Early in 1988 Norman Stone, friend of and advisor to Thatcher, wrote “Through a Lens Darkly”, a page-long article for Murdoch’s Sunday Times, in which he said Jarman’s film made no cinematic sense, before damning it and five others as “dominated by a left wing ideology”.10 Stone cited David Lean's A Passage to Indiaas the kind of cinema to aspire to, globally projecting a positive representation of our history that “toned down”11 criticisms of British colonial rule explored in E.M. Forster’s novel.

The idea that art should act as advertising for a nation’s brand didn’t sit well with Jarman, who in the same paper the following week replied:

Stone’s attack is contradictory because it

comes from a supporter of a government that professes freedom in the

economic marketplace yet seems unable to accommodate freedom of ideas

[…] the decay that permeates The Last of England is there for all

of us to see; it is in all our daily lives, in our institutions and

in our newspapers. [British films for a Hollywood market feed]

illusions of stability in an unstable world.12

But the 1980s Thatcherite neoliberal project was reliant upon hollow illusion and pretence, creation of a “Little England” with “cosmeticised historicism”13 where simulacra of an imagined history were reconstructed amongst fragments of a postwar optimism, a state-sanctified romanticisation of empire, and a new industry of exporting images.

Millennium Mills, 2018. ©The author, 2018.

***

I perceive that everything my parents had

fought for was being taken away by people of my own generation who

seemed to me were fearful people who missed out on all the more

liberating aspects of the sixties […] faced with a Tory MP a few

weeks ago on a stage I realised there was absolutely nothing there.

Actually, if you blew the whole thing would fall down […] People

think of this monumental edifice and impenetrable political situation

we’re in, but it’s not at all like that. The premises it’s

based on are completely fraudulent.

– Derek Jarman, 198914

– Derek Jarman, 198914

Architectural historian Joe Kerr says of 1977 London, “Strange pockets of silence and stillness, the spaces vacated by unwanted trades and industries […] The air of hopelessness that seems to have fallen over the city is exacerbated by the daily evidence of growing disaffection.”15 This feeling was evoked in a trilogy of Jarman films, starting with 1978’s Jubilee in which John Dee transplants Queen Elizabeth I into a devastated 1970s dystopian Britain of spaced-out squatters watching Top of the Pops, playing Monopoly, and committing murder, where plastic flowers are the only remaining urban nature. One of Jarman’s characters, a rich media mogul named Borgia Ginz, has taken over the music industry: “As long as the music’s loud enough, we won’t hear the world falling apart.”

Derek Jarman, still from The Last of England, 1987. London: Second Sight Films, 2008, DVD.

The Royal Docks closed in 1981, the latest in a gradual emptying of industry and docks moving westwards along the Thames since the late 1960s, leading to a decade of pickets, inner-city deprivation, and unemployment. While the Conservatives were in opposition, the docks became symbolic of their ambitions to change political and social structures; a 1978 speech in the Isle of Dogs by Geoffrey Howe, soon to be Chancellor of the Exchequer, called them an “urban wilderness” indicative of the “developing sickness of our society”.16 He and Michael Heseltine saw the area as a testing ground for the ideological shift they wished for state, markets, economy, and urban centres to make.

Having seen “immense tracts of dereliction”17 from a plane window, Heseltine set about forming the London Docklands Development Corporation [LDDC] after the election victory. With wide powers to acquire, promote, manage planning, and dispose of land in vast sites along the Thames as the Port of London relocated, the quango offered a platform to promote their laissez-faire urban and financial plans unhindered by local authorities, Labour councils, and opposing residents.

Over 1,550 acres of land had been acquired by the LDDC by 1988, often compulsory purchased, with pump priming from central government feeding a fund intended to lead to self-sufficiency from sales of premium-rate land on the open market. But amongst the dereliction and Heseltine’s perceived tabula rasa there were communities of homes and places of employment, just not the type that suited the area’s planned image and agenda. Other models where renewal could take place to benefit communities rather than the market were available: A People’s Plan presented alternative ideas; anarchist planner Colin Ward published Arcadia for All promoting ideas of self-organised communities; and Coin Street Community Builders were beating big developers in Waterloo. But the Docklands project could not be seen to fail, the money and political impetus behind it was too great, residents and workers simply collateral damage to the grand vision, anonymous victims of “progress”.

While not a huge fan of the music industry or artistic restrictions of pop videos, Jarman frequently used the format to explore his visual critique of state, regularly using Docklands locations as settings. 1986’s Askby the Smiths had the hulk of the Millennium Mills as a constant background, and their three-song video of the same year, The Queen Is Dead, was partially filmed in the shell of Beckton Gas Works prior to Kubrick turning it into Vietnam for Full Metal Jacket. Jarman’s camera panned graffiti: “LOCAL LAND FOR LOCAL PEOPLE”, “LDDC ARE BLOODY THIEVES”, and “OFF OUR WATERFRONT”.

From “The Queen is Dead (A Film by Derek Jarman)”, a music video for The Smiths,

©WMG (1986)

From “The Queen is Dead (A Film by Derek Jarman)”, a music video for The Smiths,

©WMG (1986)Eighties Britain was a country in which the idea of society was dismissed by a prime minister busy dismantling and privatising the very nuts and bolts from which it was built. Right to buy, selling off national industries, discriminatory taxes, increasing unemployment, systemic racism, police harassment, Irish bombings, and demonisation of AIDS sufferers. Despite this, 1986 was a success for Thatcher; fresh from victory over the miners’ strikes the prime minister set to work breaking apart the metropolitan political structures with a promise of giving control to the boroughs, and through this shifted power towards unelected quangos and private developers. Six urban centres were stripped of local governance, including the dissolution of Ken Livingstone’s Greater London Council in an all-out assault on urban Labour strongholds.

Jarman observed that Thatcher was “starting on the inner cities […] No opposition is tolerated […] dissent ruthlessly crushed […] families to be broken up by a tax on just being alive”,18 and 1985’s The Angelic Conversation explored this transformation of English landscape. A tone piece of psychological and homoerotic sequences, he called it “a dream world […] of magic and ritual”, but one with haunting undercurrents of “burning cars and radar systems, which remind you there is a price to be paid in order to gain this dream in the face of a world of violence”.19 The surveillance and destruction that hum in the background were a constant presence for Jarman, who had lived in vacated warehouses along the Thames: first a South Bank house awaiting demolition; then a Blackfriars warehouse in the way of an office tower; to his Bankside bed in a reassembled greenhouse in his warehouse space; finally to semi-ruinous Butler’s Wharf on Shad Thames. This last warehouse was lost to flames in 1980, Jarman’s westward migration through the docks foreshadowing the developers’ own movement as they followed artists, capitalising on their culture and flushing them out. As it was in the works of Milton, Blake, and Turner, fire was a recurring motif for Jarman, with some of the flames he filmed started by property developers.

Derek Jarman, still from The Last of England, 1987. London: Second Sight Films, 2008, DVD.

***

In the short space of my lifetime I’ve

seen the destruction of the landscape through commercialisation, a

destruction so complete that fragments are preserved as if in a

museum.

– Derek Jarman20

In 1986 the London financial markets deregulated, easing stock market transactions, encouraging competition of trading commissions and ending the enforced separation between stock traders and the investor advisors. This created a Big Bang explosion in the industry, requiring larger, open floors and a more global outlook for computerised and automated buying and selling of invisible finance. As John Friedmann pointed out in his 1986 “World City Hypothesis”, major importance was attached to “corporate headquarters, international finance, global transport and communications, and high-level business services”,21 and Docklands could offer all three in its new architecture. In 1988 developers Olympia & York [O&Y] broke ground on One Canada Square, a tower to rise high above the flattened docks, acting as a symbol of optimism to the world and centrepiece of a vast Canary Wharf development. At the opening ceremony, architect Cesar Pelli proclaimed, “the reality of a hollow object is in the void and not in the walls that define it”.

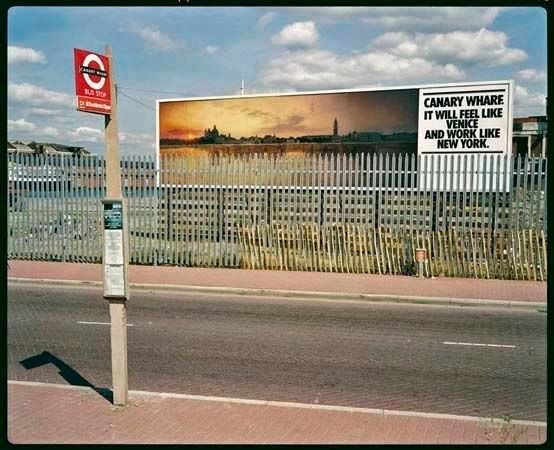

Needing to maximise income from land sales in a climate of decreasing property speculation after the Black Monday crash, the LDDC set about projecting a confident, desirable and futuristic image of the area through brand awareness, brochures, and promotional videos, putting Docklands onto a global stage.22 They had always used image and rebranding as a tool of increasing value, from presenting the docks as a hybrid of Venice and New York to whitewashing existing cultures and place names in preference of a new, on-message “Docklands”. But now new ideas were needed to promote the vast potential of the emptiness in a flailing economy, stating that “cultural regeneration might be a fair description for the process of change for which the LDDC is the chosen instrument”.23

LDDC billboard advert

The Docklands landscape was a temporal and shifting aesthetic responding to free market economics more than any grand plan. By 1988 some plots had been developed three times, each building sold to a developer who demolished it to make way for a larger, shinier project before selling on. As such, the LDDC’s initial foray into using art to bring attention to the area also looked to pop-up projects, including Peter Avery’s production of Aristophanes’ The Birds and the ICA project Accions.

In July 1988, the LDDC and O&Y joint-sponsored an exhibition of graduates’ art in a Surrey Quays warehouse. Freeze, organised by Damien Hirst and his Goldsmiths cohort including Sarah Lucas, Michael Landy, and Gary Hume, was the first step of the Young British Artists brand, later to become key to New Labour’s cultural positioning of Britain. By providing redundant architecture, LDDC garnered the kind of cultural capital that developers and “place makers” now crave ahead of regeneration, and in return the artists of Freeze got not only a venue and cash to produce a professional catalogue, but also access to the new emergent movers of business and art worlds. It also showed that for success artists had to adopt the Thatcherite entrepreneurial manifesto, or the words of Julia Peyton-Jones, who attended the exhibition and later directed the Serpentine Gallery - “Vision. Ambition. Desire. And also attitude.”24

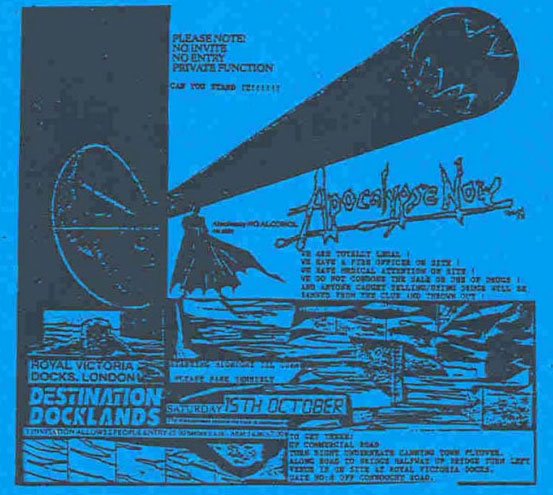

There was plenty of community-led art-activism and socially engaged practice which actively opposed the LDDC project - for example, Loraine Leeson and Peter Dunn’s collaborations with local workers, residents, and action groups for a series of billboards using montage to communicate issues within the local population. There were also diverse and political musical cultures emerging in reaction to the inner-city politics of the Conservative government, developing in small networked communities. The warehouse-party culture of house music had been developing in empty urban spaces across Britain since the start of the Eighties, emerging from black sound systems and as a response to London’s exclusive clubland culture of expense and consumerism.25

But the LDDC needed drop-in culture that could promote their brand and further ideological ambitions. It’s hard to imagine they would have supported a rave or funded The Last of England, even though Jarman arguably did more than any other artist to archive their territory and put their project into public consciousness.

Flier for Apocolypse Now rave, 15 October 1988, Docklands.

***

I think this show here tonight might wake up the city.

– A spectator at Rendez Vous Houston26

1986 the USA was also struggling with post-industrial reshaping. Houston was in the peak of an oil-slump, unemployment crisis, and real estate collapse. Two months earlier a failed O-ring had caused the space shuttle Challenger to spectacularly break up and explode, killing all seven crew members, live CNN footage providing one of the world’s first live-streamed disasters of the information age. Houston was then a collapsing city where even Texan bravado couldn’t conceal the despair, damage, debt, and mass defaulting of mortgages.

The city needed a kickstart and so the authorities invited French electronic musician Jean-Michel Jarre to use the city as the stage for a pop spectacle on a scale never before witnessed. Vast white sheets were draped over downtown skyscrapers transfiguring them into giant canvases for video projections, a backdrop for 1.5 million Houstonians to stare up at amongst searchlights, lasers, and fireworks set to the electronic music of Jarre.

Jarre was a child of the baby-boomer generation and son of Maurice, globally renowned composer of music for over 170 films and TV shows over five decades, most remembered for scoring David Lean’s epics including A Passage to India. This classical heritage lingered in Jean-Michel, who would later enrol to study piano at the Conservatoire de Paris. By day learning classical skills of the institution, by night playing the guitar for several bands including in a brief party scene on film in Des Garcons et des Filles, a 1967 comedy following communally living students in a soon-to-be-demolished derelict house.

In 1968, amongst the cacophony of student protests (internet fan message boards talk of lost TV footage showing Jarre being handcuffed and thrown into a police van), he abandoned the conservatoire and joined Groupe de Recherches Musicales, an electro-acoustic experimental organisation created by Pierre Schaeffer, creator of experimental musique concrete. Jarre’s music quickly found a fusion between the mechanical rhythms developed under Schaeffer and his classical training, with chart success leading to a free 1979 Bastille Day concert for a million Parisians.

Two years later Deng Xiaoping invited Jarre to become the first Western artist to perform in communist China. The mix of largely lyricless tradition and technology that marked the French Revolution deemed safe enough for a somewhat bemused Chinese audience. Then came Houston and its grand civic boosterism.

Jean-Michel Jarre, from The “Making of Destination Docklands”,

©Mike Mansfield Television (1989).

Jean-Michel Jarre, from The “Making of Destination Docklands”,

©Mike Mansfield Television (1989).

“Spectacular,” “imaginative,”

“amazing”. Words that can be applied equally well to a Jean

Michel Jarre concert or the development of London Docklands.

– LDDC advert in the Destination Docklands souvenir brochure27

– LDDC advert in the Destination Docklands souvenir brochure27

Just as images of the Challenger exploding in mid-air spread across the world, so too did footage of Jarre’s Rendez-vous Houston. In London, media-savvy employees of the LDDC may have seen MTV clips or read about the urban spectacle because while Jarre discussed repeating the concept across other US cityscapes, with meetings lined up in New York and Los Angeles, London’s Docklands would be the next setting for his architectural take-over. The concert “Destination Docklands” and partnering album Revolutions hung on a three-act structural device of industrial, 1960s cultural and contemporary technological social shifts. As well as offering a stage for the show, this was an opportunity for the LDDC to project its brand identity and message across the world. Perhaps loudly enough that nobody could hear the Docklands economy falling apart.

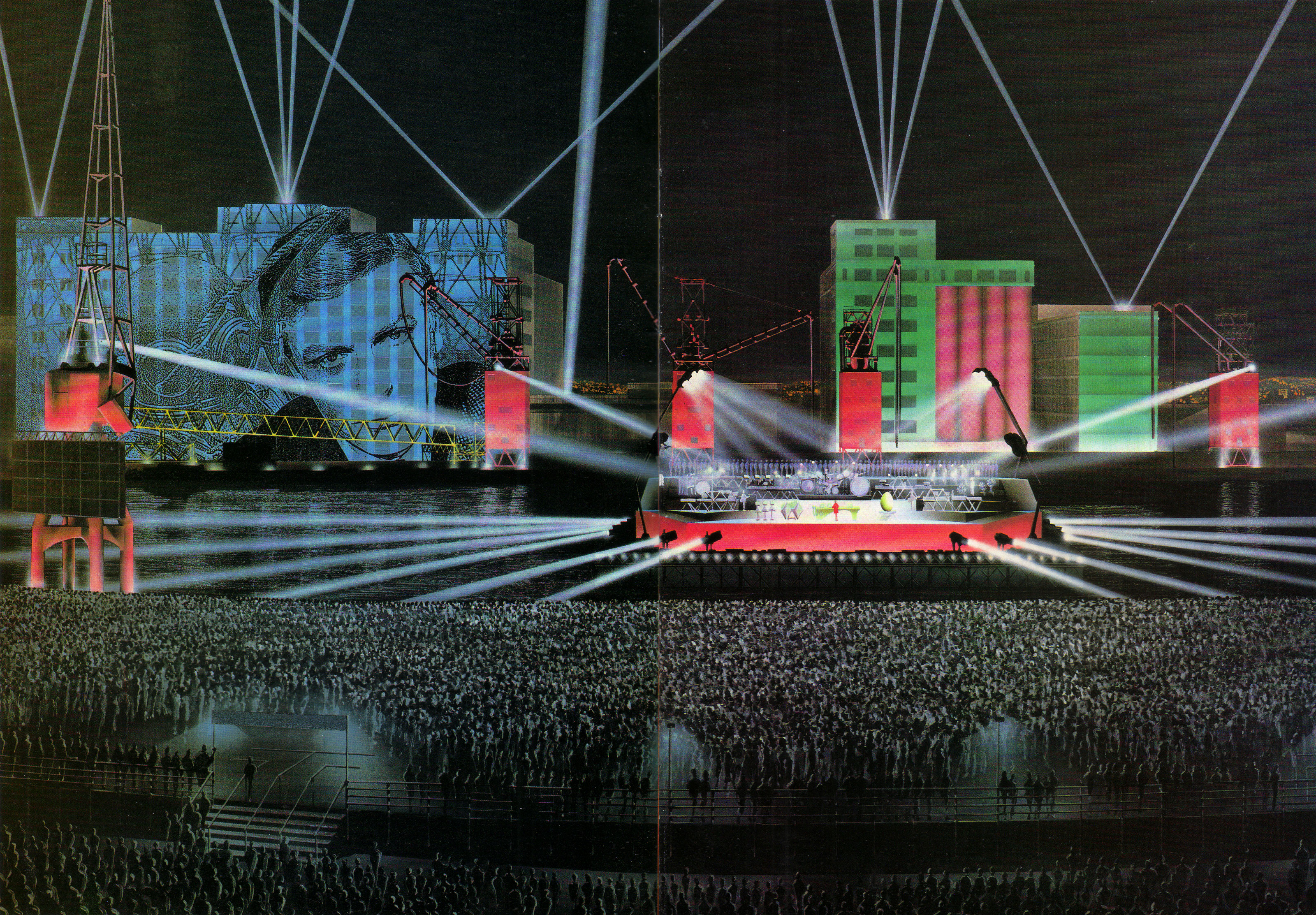

As with the transformation of Houston, Jarre partnered with British architect Mark Fisher to turn buildings into scenography. Also a baby-boomer, Fisher had trained at the Architectural Association during their mid-Sixties exploration of radical new ideas for architecture and society: pop-up, portable, inflatable, walking, DIY, ephemeral, and cybernetic. From 1969 Fisher studied for his diploma under Peter Cook as the Archigram founder pushed the architectural agenda towards pleasure, questioning rules of the elite and pulling inspiration from popular consumerism as much as classical tradition. Jarre partnered with him for his architectural extravaganzas after Fisher had already designed The Wall for Pink Floyd and taken his utopian trainings firmly down the path of spectacle and sensation.

Fig. 6: Mark Fisher, The Stage from the Royal Box, official concert programme. ©Concessions Ltd, 1988.

Fig. 6: Mark Fisher, The Stage from the Royal Box, official concert programme. ©Concessions Ltd, 1988.As a spotlight traces across the sky I would

think there are a lot of people in Newham who would remember World

War II who will have themselves jerked back into the 1940s this

evening.

– Simon Bates’ Radio 1 live commentary of Destination Docklands28

– Simon Bates’ Radio 1 live commentary of Destination Docklands28

The concert nearly didn’t happen; two weeks before its intended September date the fire services pulled the plug on safety grounds. A frantic period followed in which Jarre visited other cities - the site of Liverpool’s Garden Festival empty since the 1984 event, Glasgow, Manchester, Thurrock, Newcastle, even Alton Towers. It created a media storm and the kind of neoliberal intercity competition now built into national cultural mechanisms. But it may have all been a ruse to scare Newham and the LDDC, and after an extraordinary council licencing meeting for which Jarre flew in, it returned to its site of inspiration, Docklands, albeit for a delayed October date.

Fisher’s visual design of the project was massive. The façade of Millennium Mills had been painted white to offer a vast surface for projected images, part of an enormous triptych including the Co-operative Wholesale Society Mills, an immense 90x100 metres scaffold structure. The concert programme lists some of the projected imagery, offering a snapshot of the curated narrative:

Part 1: Industrial Revolution

empires

deserts

jungles

industry

emigrants

commerce

Part 2: Cultural Revolution

hitchcock

quant

twiggy

vietnam

avengers

caine

Part 3: Electronic Revolution

leisure

silicon

comsat

replicant

deconstructivist

revolutions

Fig. 7: “Destination Docklands”, Jean-Michel Jarre, 9 October 1988. (Photographer unknown.) Available on

Fig. 7: “Destination Docklands”, Jean-Michel Jarre, 9 October 1988. (Photographer unknown.) Available on

Jean-Michel Jarre’s website.

At other points the words “employment” and “no employment” were cast over the hulk of the mill, visible for miles across the very neighbourhoods suffering since the docks’ closure. Two hundred and fifty thousand pounds’ worth of fireworks, equivalent to the total costs of The Last of England, exploded above the docks and World War II searchlights reflected off clouds. Later, the previous year’s violence caused by social inequality and deprivation was visually represented by fireworks and projections of flames described by Radio 1 DJ Simon Bates as giving “the impression that the warehouse opposite with its windows red and smoke coming out of them is ablaze”.29

This is where Jean takes a musical […]

look, at what he believes will happen to the Docklands area in the

1990s. And of course is using this enormous and clumsy, or

clumsy-looking, pair of asbestos gloves for his guitar which

otherwise would electrocute him.

– Simon Bates’ live commentary30

– Simon Bates’ live commentary30

At one point an image of a modern office building was projected over the top of the Millennium Mills, giving the slightly macabre impression of a shroud, perhaps a marketing gimmick for the LDDC trying to at once acknowledge and disguise the dirty industry of the area. When Jarre puts on a pair of asbestos gloves to break the green divergent beams of his trademark laser harp, it is impossible not to think of the asbestos embedded into the docks which would have led to the premature deaths of countless industrial workers. An industrial material transfigured to function the new service and culture economy.

From “Destination Docklands: The London Concert”.

©Dreyfus records, (1988)

From “Destination Docklands: The London Concert”.

©Dreyfus records, (1988)The stage formed of ten lashed-together barges shipped from the northeast was designed to float from left to right in front of the crowds, but the sheer weight of equipment and performers rendered it motionless. British autumnal weather deluged the site. Improvised tarpaulins were lashed over equipment while rehearsals saw musicians fighting winds to stay on the floating stage. But despite the technical and seasonal issues, the sheer immensity of spectacle dominated the Royal Docks; footage shows searchlights darting across a sea of static faces starring up in awe.

Jarre’s said his concert was “a tribute to the anonymous victims of every revolution”,31 dedicating the album to “all the children of the revolution” and “the children of immigrants”.32 In a coincidental mirroring of The Last of England, the concert ended with Jarre’s song L’Emigrant, a choir of local children - wearing lifejackets in case they fell from the floating stage - offering harmonies to a crescendo of classical and electronic instruments wrapped up in the drama of relentless firework explosions.

From “Destination Docklands: The London Concert”.

©Dreyfus records, (1988)

From “Destination Docklands: The London Concert”.

©Dreyfus records, (1988)

No-one seems to have moved in almost two

hours. They’re standing rock still, loving the fireworks and now

seeing “Newham” projected in large letters on the two buildings

opposite the stage.

– Simon Bates’ live commentary33

– Simon Bates’ live commentary33

This was a total spectacle in a Guy Debord sense. The romanticising of empire and industry and the simplification of the area’s history into a neat narrative to further the LDDC agenda, fits his notion that ”spectacular consumption preserves the old culture in congealed form”.34 Crowds stood on the dockside, once busy with workers, silently facing the Millennium Mills, enacting Debord’s “deceived gaze and […] false consciousness”, their sense of shared experience “nothing but an official language of separation”.35 In many ways this event was the counter to the rave culture developing over the previous few years which appropriated locations for community-organised parties; this was an on-message, state-sanctified appropriation of place and history to help the wider objectives of the LDDC.

Outside, ticket touts showed the kind of entrepreneurial spirit that would have made Thatcher proud, selling £30 tickets for £50, making £2,000 in an afternoon. While inside, away from the raked seating and vast tract of post-industrial land for the 100,000 punters, sponsors and businessmen enjoyed the corporate entertainment. A video produced by the main sponsor, the Carroll Foundation Trust, intersperses the performance and visuals from the stage with footage from the corporate marquee, businessmen mingling with dignitaries, sponsors, and celebrities. This is where Gerald Carroll worked the room, shaking hands and posing for photos, inviting the key figures of the period to his party. Princess Diana. Robert Maxwell. Jeremy Beadle.

From “Destination Docklands: The London Concert”. ©Dreyfus records, (1988)

Our society is built on secrecy, from the

“front” organisations which draw an impenetrable screen over the

concentrated wealth of their members to the “official secrets”

which allow the state a vast field of operation free from any legal

constraint, from the often frightening secrets of shoddy production

hidden by advertising, to the projections of an extrapolated future.

– Guy Debord36

– Guy Debord36

Derek Jarman said of authority, “all I saw was deceit and bankruptcy”,37 and in 1992 some of the walls surrounding the hollow voids of finance collapsed. Robert Maxwell, who along with his son Ian received a “special thanks” from Jarre in the liner notes of the live album, drowned after leaving the Mirror Group’s pension scheme drained. Gerald Carroll, who in 1986 put his entire business portfolio, assets, houses, and art into his Foundation Trust, saw his speculative empire collapse in massive debt and allegations of fraud. Hollow objects. The promoters of Destination Docklands ran up spiralling bills from the delay, weather, and sheer scale, leaving countless suppliers and workers unpaid for their work seeking damages in the courts - the projected façade of the spectacle concealed the failures of its production.

Even counter-cultures got absorbed into the late-Eighties neoliberal race for profit. The warehouse rave scene was turning from community-led right-to-the city activation of redundant spaces into an entrepreneur-led business. Saving money earnt from gambling to enter property development, Tony Colston-Hayter turned raves into vast pop-up festivals, inviting media attention and consequential police pressure against the rave scene. His PR manager Paul Staines, then working in a Conservative Party right-wing pressure group and now as blogger Guido Fawkes, considered Colston-Hayter one of “Thatcher’s children” with an entrepreneurial spirit “pushing the boundaries of free enterprise”.38 This was when the culture industry exploded, and everyone wanted some of it, or to benefit from its glory.

“Destination Docklands”, before the concert, 9 October 1988. ©Dennis/Spitfire 13, 1988. Available

“Destination Docklands”, before the concert, 9 October 1988. ©Dennis/Spitfire 13, 1988. Available

on Flickr.

We’re live on Radio 1 in stereo, on FM.

We’re broadcasting the Destination Docklands concert as it happens

from, guess where, from Docklands, with 100,000 people. It’s

freezing cold here. On my left-hand side are camera crews from

Brazil, the USA, from Canada, from Germany, from all parts of Europe,

from Australia, from New Zealand. They are absolutely frozen but

hypnotised by what’s happening on stage and in and around the

docks.

– Simon Bates’ live commentary39

– Simon Bates’ live commentary39

Destination Docklands was one of the first globally mediated cultural events on this scale, incorporating the music, dance, fireworks, architecture, and awed crowds now firmly embedded in contemporary pop culture. Fisher would continue to revolutionise the large-scale pop spectacle, developing the superstructures that U2, the Rolling Stones, Lady Gaga, and Elton John carry around the world - the lo-fi radicalism of 1968 subsumed into the late-twentieth-century capitalist drive for sensation and scale. This sense of event is now rolled up with neoliberal hypergentrification and push for vast capital returns on urban redevelopment. The launch of Canary Wharf’s tower in 1992 and that of the Shard in 2012 were mediated affairs with live music, lasers, and searchlights.

The visuals of industrial workers, Queen Victoria, colonial success, pop revolution, and James Bond that congealed the Millennium Mills in light were witnessed again for the 2012 Olympics Opening Ceremony up the road in Stratford. Seen by a global audience of a billion, the ceremony was executive produced by Fisher and had similarities to Jarre’s sequenced narrative of eras set to a classically infused pop beat. No modern-day event is as spectacular as the Olympics, loud enough to distract from the compulsory purchasing of land from profitable businesses and rooted communities to make way for the grander and shinier cultural offerings planned to follow the few weeks of sport.

“Destination Docklands”, before the concert, 9 October 1988. ©Dennis/Spitfire 13, 1988. Available

on Flickr.

Millennium Mills has now been scrubbed clean for the next chapter of its life. The docks it sits within have been undergoing another cleansing since the 1980s to form a “new piece of the city”.40 There is no space in that new city for the narratives that Jarman explored, there is no room for other narratives to the prescribed, official one. The trajectory of neoliberal urban politics since 1988 has taken us to a place where it has become harder to separate the function of art from the wider capital economy. It is now so deeply enmeshed within the very physical changing face of London, even if it’s only a sacrificial veneer or a popup spectacle moment. The Millennium Mills have not only survived throughout, now a single white tooth standing as the history and architecture has been extracted but have been repeatedly co-opted into the changing representation of the area.

Congealed, a preserved fragment.

ENDNOTES

1 “Silvertown.” http://www.silvertownlondon.com.

2 London Development Agency. “London Mayor Ken Livingstone Launches London’s Silvertown Quays and Reveals Plans for World-Class Visitor Attraction to an International Audience at MIPIM 2005”.

3 The internet is awash with urban exploration photographs from Millennium Mills, including HERE, HERE and HERE.

4 Ahmed Jamil, “BLOC 2012 @ London Pleasure Gardens”, 6 July, 2012, HERE.

5 Stop City Airport Masterplan, “Press Release-Toxic Asbestos Risk at London Pleasure Gardens.", HERE.

6 Norman Stone, “Through a Lens Darkly”, the Sunday Times (10 January 1988)

7 Derek Jarman, Kicking the Pricks (Vintage, 1996), p. 208.

8 Ibid, p. 188.

9 400 Blows, “Gaye Temple (nee Jarman) on Derek Jarman.” HERE.

10 Norman Stone, “Through a Lens Darkly.” Sunday Times, January 10, 1988.

11 “A Passage to India: David Lean’s Rocky Road to Creating a Most Powerful Adaption”, Cinephilia & Beyond, HERE.

12 Michael Charlesworth, Derek Jarman (Reaktion Books, 2011), p. 134.

13 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 81.

14 Derek Jarman, “Derek Jarman in Conversation with Simon Field,” interview by Simon Field. ICA Guardian Conversations, 1989. Video, HERE.

15 Joe Kerr, “Introduction”, in Andrew Gibson and Joe Kerr (eds), London from Punk to Blair (Reaktion Books, 2003), p. 29.

16 Timothy Weaver, Blazing the Neoliberal Trail: Urban Political Development in the United States and the United Kingdom, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016), p. 253.

17 Fiona Rule, London’s Docklands: A History of the Lost Quarter, (Ian Allen, 2012), p. 91.

18 Dennis Sewell. “Not the Last of Jarman.” Spectator, May 7, 1988.

19 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 133.

20 Ibid., p. 136.

21 John Friedmann, “The World City Hypothesis.”, Development and Change, 17:1, January 1986, pp. 69-83.

22 Taner Oc & Steven Tiesdell, “The London Docklands Development Corporation (LDDC), 1981-91: A Perspective on the Management of Urban Regeneration.”

23 Robert Maycock, Regeneration and the Arts in London Docklands (LDDC, 1998)

24 Elizabeth Fullerton, “How Britain’s Shocking Art Movement got its Start”, BBC Culture (25 April 2016), HERE.

25 Jon Savage, Time Travel: Pop, Media and Sexuality 1976-96 (Chatto and Windus, 1996).

26 Rendez-Vous Houston – A City in Concert, dir. Bob Giraldi, (Disques Dreyfus, 1989)

27 From the Destination Docklands official programme.

28 Simon Bates’ BBC Radio 1 live commentary of Destination Docklands.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 From the Destination Docklands official programme.

32 Liner notes to Jean-Michel Jarre, Revolutions (Disques Dreyfus, 1988).

33 Simon Bates’ BBC Radio 1 live commentary of Destination Docklands.

34 Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, trans. by Donald Nicholson-Smith, (Zone, 1994), p.192.

35 Ibid., p.52.

36 Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, trans. by Malcolm Imrie, (Verso, 1990), p. 52.

37 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 181.

38 Paul Staines, “How did Acid House Change the British Music Scene?” Interview by Annie Nightingale, BBC Today (16 November 2013), HERE.

39 Simon Bates’ BBC Radio 1 live commentary of Destination Docklands.

40 “Silvertown.” HERE.