Billboards as a site of urban conflict: Advertising & subvertising in neoliberal London

Comment2019

Our urban spaces are ones not only saturated with the imagery and slogans of advertising, but it increasingly seems as if urban form predominantly exists to supply a scaffolding of surfaces and stream of eyes for an advertising sector looking to squeeze marketing opportunity from every inch of the street. It’s nearly impossible now to imagine navigating a city without a constant shout of slogans and logos, for a pedestrian they are as much a part of the urban experience as the physical terrain, and provide a constant visual noise on a par with the drone of traffic.

Over the last few weeks four men - Richard, Adam, Chris and Dave - have been transgressing that space of consumerism, disrupting the sanctity of aggressive, cunning marketing. Under the banner Led by Donkeys, they have been enlarging historic tweets of pro-Brexit politicians and showing them up as apparent self-serving hypocrites who now publicly act against their prior convictions.

(Image © CliningPandas, from their Twitter account)

(Image © CliningPandas, from their Twitter account)

They have simply been hiring the advertising spaces usually adopted by car, junk food, disposable fashion and cosmetics which imply we can all be supermodels, and pasting up verbatim political statements by those who now suggest the absolute opposite is best for us all. Then, the magic of observant citizens and social media does the rest - the images going viral before being retweeted in the Led By Donkeys Twitter feed by the guys behind the simple but powerful stunt.

But this interruption into the apparent status-quo of consumerism embedded into the fabric of our built environment is rare, and it is through using the billboard sites in such a way that both gives the campaign its power as well as reminding us just how used to this relentless veneer of marketing we have all become, the shift in purpose giving us a glimpse into a possible world where political discourse is as important to the public realm as that of the sell, sell, sell mantra.

When artists or imaginaries conjure up worlds in which adverts are not so commonplace, the city appears alien, almost unrecognisable so deep-rooted is the amalgamation of place with embedded capitalist marketing. In artist and activist Rab Harling’s excellent 2009–10 series Abandon Your Dreams, which “questions whether our status as individuals has been undermined as we become tools to consume and generate growth in order to support a fundamentally flawed ideology”, the city is not only wiped of marketing but also of us, the people who give our attention to the billboards as they give us instructive late-capitalist guidance. Symbiotic relationships are the hardest to break, and one wonders how a city could be de-advertised when it appears as such a function of the urban experience.

(Image © Rab Harling, from the artist’s website)

(Image © Rab Harling, from the artist’s website)

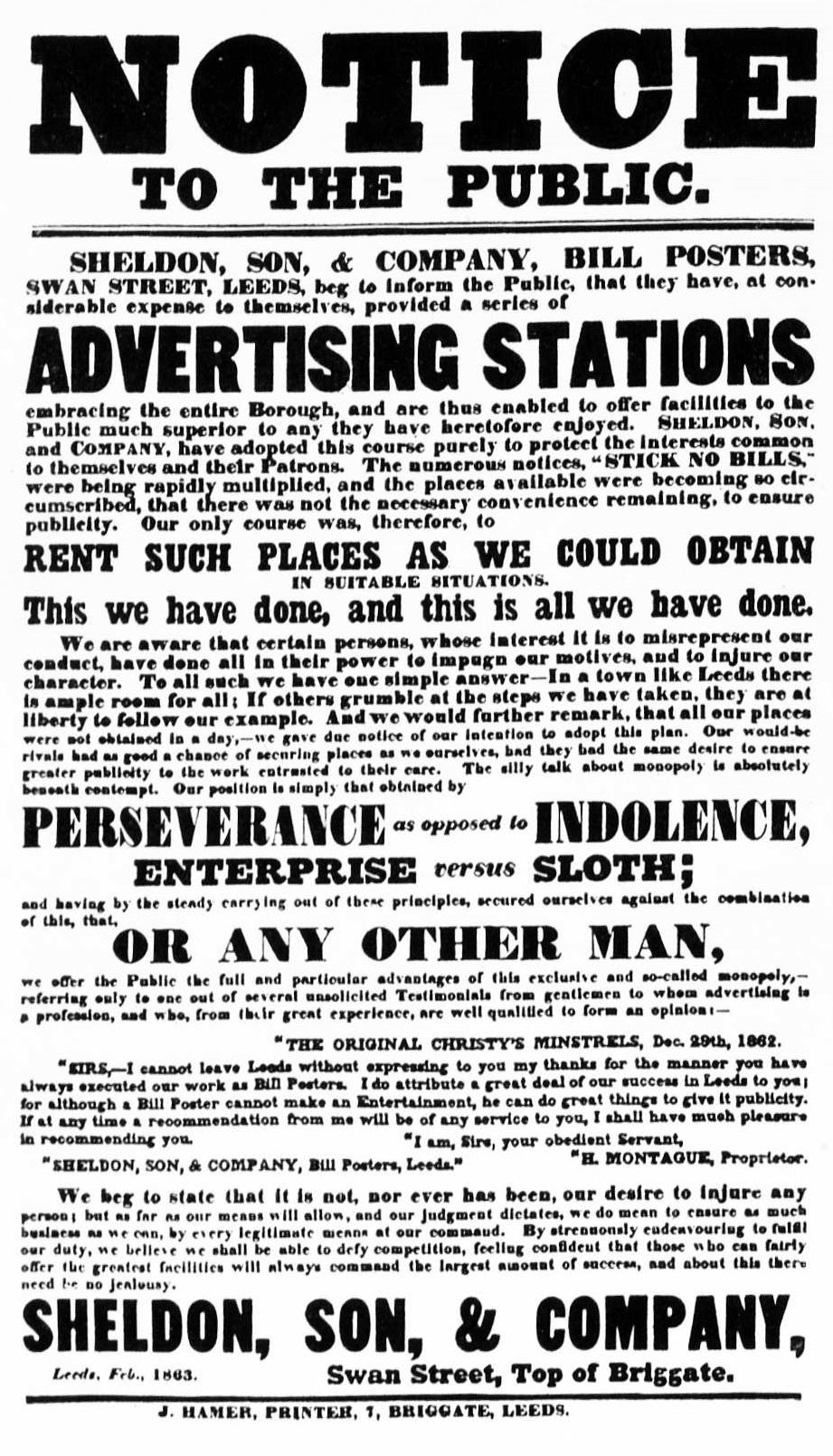

Looking through the 1953 book Outdoor Advertising, it’s Function in Modern Advertising and Marketing (with a forward from the Imperial Tobacco Company), it’s clear that this interdependency of modern urban space and the sales opportunity it offers is hardwired into the post-war urban infrastructural economy of London and Britain. It cites Leeds billposter Edward Sheldon as an early adopter of licensed outdoor advertising which rose in popularity in the mid-19th century following acts which outlawed posting of bills on property without the owners permission.

These acts laid the foundations of a new way of sweating capital from urban space, from the very surfaces of the buildings one owns, compressing capital into the very veneer of our built space and offering up the whole city as a potential frame for consumerism. This Sheldon, Son & Company poster is an advert itself advertising their commitment to sell advertising, with endorsement from previous happy customers including “The Original Christy’s Minstrels”:

(Image from Outdoor Advertising, its Function in Modern Advertising and Marketing)1

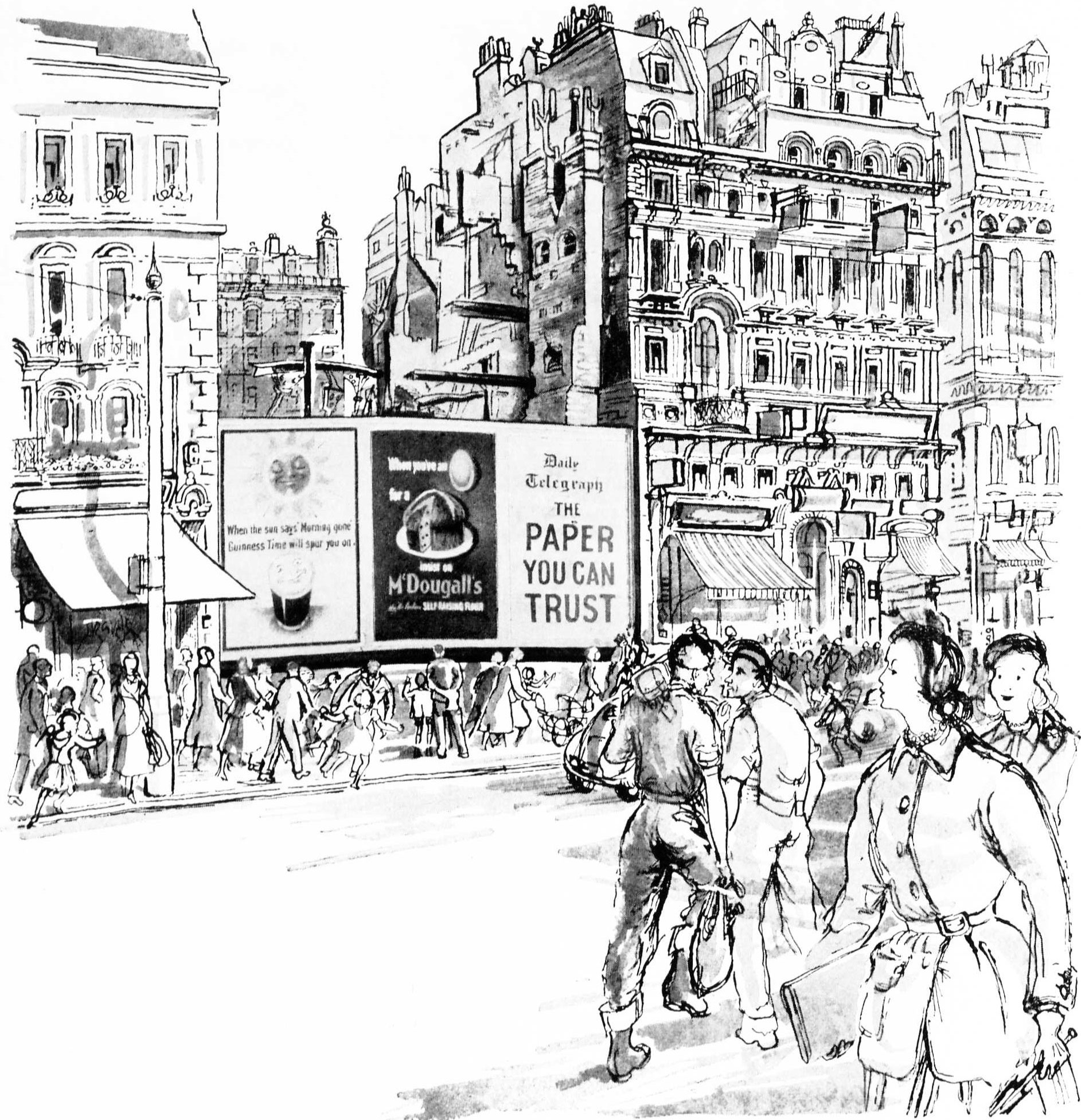

(Image from Outdoor Advertising, its Function in Modern Advertising and Marketing)1Just as the printed advert and window displays had altered the city experience in the century before, as articulated by Walter Benjamin and others so profoundly, new modes of advertising would alter the very city form itself. London and other British urban centres in the 1950s were covered with the scars of war, derelict buildings, bombsites, gaps in streetscapes and a fragmented urban whole which worked as a constant reminder of the recent trauma. Capitalism had offered itself up as the answer not only as having the wonderful products which would improve everyone’s lives for the better, but also that this new generation of advertising could offer the very mechanism of improving our urban existence in new ways.

In an image from 1953’s Outdoor Advertising, titled “closing the gash of war”, the billboard itself is offered up as an aesthetic solution to heal the wounds of conflict and remedy an aesthetic blight:

(Image from Outdoor Advertising, its Function in Modern Advertising and Marketing)2

(Image from Outdoor Advertising, its Function in Modern Advertising and Marketing)2

The authors, however, do see limitations of where such marketing should be deployed: “Clearly there are certain places where poster sites are out of place — the countryside, the areas around cathedrals and historic monuments, and so on”.3 Though it was only the following year that Coca Cola installed their Piccadilly Circus illuminated sign, a spot they still hold to this day, in a modern intermingling of cultures whereby historic monument is the advertising site itself.

I come to be thinking of billboards because everyday advertising like this seems to be cropping up more and more in the news. A friend sent to me a link to the recent collaboration between French artist Martin Firrell and advertising organisation Clear Channel, asking if I had seen any of the interventions exploring “gender and power” on my walks around London.

(Image © Martin Firrell, from the artist’s website)

(Image © Martin Firrell, from the artist’s website)

I haven’t. And I really don’t want to. Firrell is a self-proclaimed “public artist who stimulates debate in public space to promote positive social change” and his collaboration with Clear Channel is stated by the advertiser as “a series of public art works to provoke conversation, celebrate creativity and promote fairness”, obviously all with the Clear Channel logo prominently under the very woke slogans.

That a message like “distorted power and great inequality are evil” are championed by an agency which is part of a global conglomerate with multi-billion dollar revenues often derived from marketing products which cause immense damage to human health and help fuel an unrealistic image of beauty and body perfection, seems odd to me. Nearly as odd as his 2017 “Remember 1967” series with slogans such as “Homosexuals and women are systematically oppressed by male supremacist society” and “Embrace lesbianism and overthrow the social order”, celebrating the anti-establishment social uprising of the mid 1960s in partnership with establishment advertising agencies PrimeSight and Clear Channel UK.

Firrell is not afraid of partnering up with the most powerful agents in society in his stated interest of upsetting the social order: he has worked with the Church of England,British Army, and Royal Opera House. At a time when institutions of all kinds see value in artwashing their image through relatively cheap partnerships with artists in projects which help soften a corporate, heavy or socially damaging image, the projections and slogans of Firrell are a clear win-win for advertising agencies finding a Brexit-induced downturn in demand for urban billboard sites. He gets a platform, the company present the image of a woke social awareness, the public get a moment of juxtaposed and unexpected political blandness, nobody is really that offended. Good job all round.

Just as in 1953, advertising was presented by the industry as a solution, rather than exploitation and commodification of public space as it clearly was, so it is today presented as a generous solution to contemporary urban ills. The UK Chief Executive of Clear Channel recently stated that we “underappreciate” the social importance of urban advertising, and that the estimated £390m a year which the industry pays in rents and rates underpins the public infrastructure supplied by local and transport authorities.

A lot of the advertising money that comes in at the top goes straight back out to fund public infrastructure projects… We spend a lot of money creating better infrastructure, better streets, helping with travel propositions.

Sure, Clear Channel, PrimeSight and JCDeceaux may pay for bus shelters, but they are not interested in public transport or urban social infrastructure beyond the fact they can use it to create more flat surfaces of marketing in spaces of an audience hanging around waiting for a bus. It is also the case that much of the social infrastructure they claim to benefit society, such as the proliferation of street internet/phone stations are simply a mask of generosity to open up lucrative new advertising real estate bang in the middle of the pavement, directly in front of pedestrian’s eyes, outside of regular planning processes.

This pro-civic-good position is a position taken by Clear Channel amid a crackdown in certain types of advertising, including that of junk food near schools and bodyshaming beauty products. To side with the stance that every piece of transport, social or urban infrastructure must operate as a promotional opportunity is to side with the total free-marketisation of the public, to allow function and need to be subordinated to the greater demand of constant financial profit and a relentless increase in a consumerised citizenship.

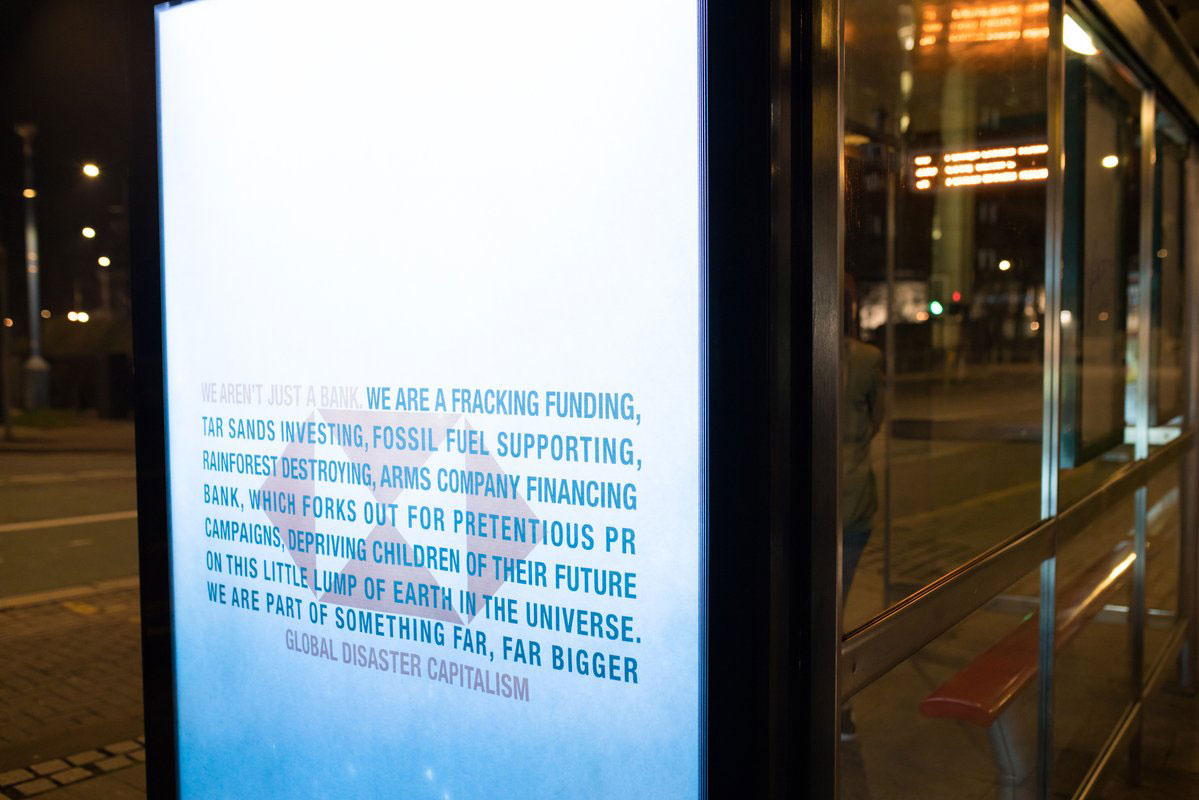

This kind of civic-minded corporate sloganising hit British cities in the most unsubtle form recently, with the global Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation presenting the image of being at one with the austerity-hit person on the street and not in fact a faceless dominant entity of capital regularly connected to money laundering. No, they are the plucky local business that cares about you, in an exercise of corporate placebranding which journalist Dan Hancox suggested in a recent Vice article is to correct their actual image: “global, placeless, depersonalised — circling the globe like the ozone layer.”

The campaign, which also focused on Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, was widely criticised and mocked, but it also has to be acknowledged that it was also widely posted on social media by people proud of their city and seeing HSBC as an ally to not only their city, but to them as an individual. The billboards that were once sited to paper over the bombed out hollows in our streets can now be seen to be papering over the gaps in our confused late-capitalist, pre-Brexit social identities. Brands to the rescue: the civic and social heroes that they are.

In the decay of 19th century shopping arcades, Walter Benjamin saw a way of looking at the city beyond consumer mirage of spectacle and helped us see the very fragility of capitalism for what it was, a veneer and presentation of control and wonder. That glimpse beyond offered a space of urban imagineering, opening up space for possibilities of new ways of politics and being.4

Place-branding seeks to cover these ruptures, using the image of togetherness and association to conceal not only the physical but also the psychological and social issues urban citizens face in 2019.

The ongoing creative act of Brandalism and Subvertising, by which people make changes to existing advertising or simply co-opt existing advertising space and insert their own subversive messages, fights against all the previous examples of slogan-led citizen subjugation. The use of adapting corporate advertising space for an activist function is not a new one, and as Naomi Klein points out in her seminal book No Logo, San Francisco’s Billboard Liberation Front and Australia’s Billboard Utilizing Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions have both been operating since the late 1970s,5 and in London at the moment there seems to be an interesting clash between a citizen-led subversive appropriation of advertising space, and a corporate-led intent to appear local and matey with the locals.

(Image © Darren Cullen, from Twitter)

London subvertisers Special Patrol Group have an ongoing social media feed of fine examples of reclaiming the public space for critical discourse and thought from the sloganeering of brands, advertisers and all who design the city political and aesthetic. They also give simple guidance of how to hack bus-stop adverts so you too can insert your own messages, disrupting the control and order and allowing a space for civic voice.

Their recent collaboration with artist Darren Cullen saw Underground trains decorated with a satirical property advert for a fictional luxury development “Bellend Palace” which arguably offered more scope for a commuting Londoner to identify with more than the patronising HSBC effort. Another parodied BAE Systems, Airbus and the British Governments work in Yemen, another was for Jesus Christ’s new van hire company, and then one highlighting mobile phone tracking.

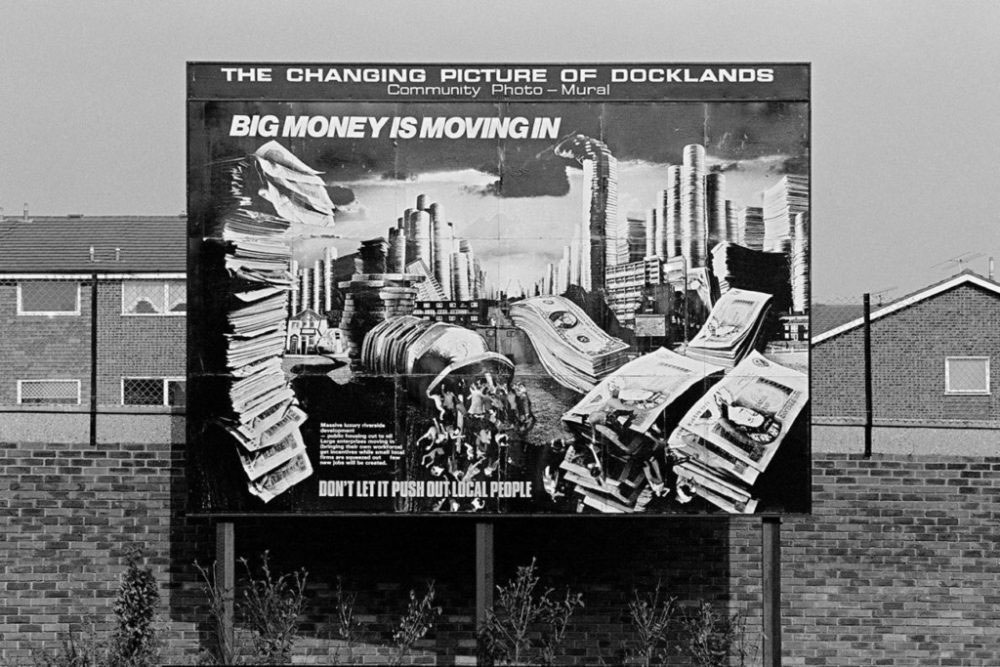

This is just the latest in a long line of appropriation of advertising space for a publicly minded retaliation. In the 1980s the Docklands Community Poster Project by Loraine Leeson with Peter Dunn sought to use the space and approach of billboard advertising to fight against the all-encompassing powers of the developers and quangos which were rapidly rearranging communities and redeveloping vast stretches of the London docks. Designed not to address the developers or agents of change, but the very local communities who were affected, the artists created evolving series of photomontages to act as catalysts of direct action and to bring into public awareness the processes and motifs which were behind the urban change.

Similarly, the Justice4Grenfell campaigners adopted the iconic imagery from award winning 2017 film Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri to raise public awareness about the very human toll and ongoing lack of culpability for the tragic and avoidable tower block fire which resulted in 72 deaths. The three message-laden vehicles parked up outside Parliament after a capital tour past the sites of wealth and power so at odds with the helplessness of those who were both trapped in the tower on the night and those who since have been fighting for change and acknowledgement of the need for systemic change. The Oscar winning actress from the film from which the campaigners took the idea supported the activist actions, stating “Billboards still work”.

In his 1967 book, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Marshall MacLuhan wrote, “The steady trend in advertising is to manifest the product as an integral part of large social purposes and processes.”6 While MacLuhan concentrates on the modern advertising approaches of the day, the televised and mass-mediated, the underlying foundations he noted are as visible in the age-old printed adverts as we see on the tube or billboards in our public spaces. Imagine a world where public debate and political discourse was as integral to our urban experience as that of selling us crap, that we were citizens before consumers.

Led By Donkeys have shown us that this is possible, with just a small amount of cash, public curiosity and interest, intelligence, cunning and humour. The system can be appropriated to a different end, a dialogue rather than simply reception of messages. Other groups are doing brilliant work, including Adblock Bristol, Reclaim The Power and Brandalism UK, and are showing that it is possible to deliver political messaging parasitically using the existing neoliberal structures rather than “collaborating” with them on bland boardroom-OK’d messaging which brandwashes the corporation and artist involved more than delivering any sincere, direct and critical messaging.

Just as there is an ongoing urban struggle to Reclaim the Streets, and an ongoing interest in drawing from Heni Lefebvre’s words in Le Droit a la Ville (The Right to the City)7, so too there is an ongoing struggle to reclaim the space of urban messaging. In this unique time of British history, with political fractions, environmental change, Brexit uncertainty and neoliberal corporate desperation, the urban message space is a contested territory, and while the large capitalist and governmental agencies (and their selected willing partners) may control the power, the citizenry have, as they always have, the wit, intelligence, speed and concern to ensure it doesn’t always go the way of the dominant voices.

(Image © Led By Donkeys, from their Crowdfunder page)

(Image © Led By Donkeys, from their Crowdfunder page)

- Richard Nelson & Anthony Sykes, Outdoor Advertising, its Function in Modern Advertising and Marketing. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1953. P.10

- Ibid. P.66

- Ibid. P.107

- See Anne Cronin, Advertising, Commercial Spaces and the Urban. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. 2010. P.127

- Naomi Klein, No Logo, London: Flamingo, 2000. P.289

- Marshall MacLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, London: Sphere Books, 1967. P.241

- See the free Verso books primer into the modern day rendering of the rights to the city in: The Right to the City, a Verso Report, London: Verso, 2017. Accessible from: https://www.versobooks.com/books/2674-the-right-to-the-city

(Image © Mike Seaborne, from the

(Image © Mike Seaborne, from the