London: What can we learn from Cadiz?

Essay2018

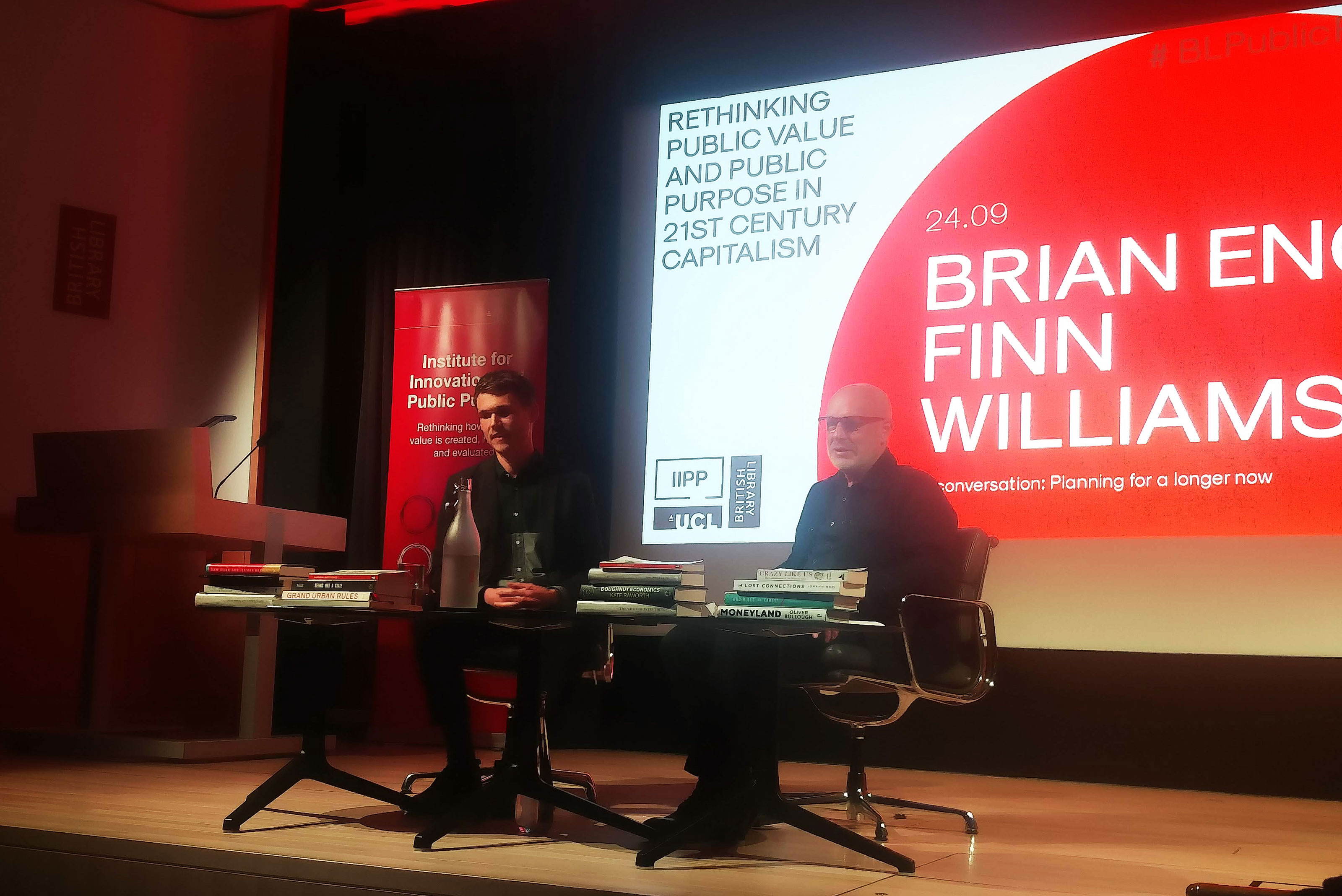

I was recently at at a discussion between Finn Williams of Public Practice, an organisation interested in new modes of urban planning, and legendary musician, artist and thinker Brian Eno as part of the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose series of talks on public value. The discussion covered a range of areas related to public, focused around economics and place. Eno made a passing comment about a recent holiday that lingered with me as I travelled home on the Underground.

Talking of architecture and how urban forms develop, he suggested “speculative things are likely built by dictators, but the things we love are built by many people banging into them”, suggesting that the generative processes of community and co-existence shape urban space through dialogue and evolution in a more human and endearing than top-down policy and free-market forces. He then mentioned a recent holiday in Cadiz, Spain, where he considered the tightly packed old-town core to have been shaped through care, an empathy and awareness of other city users.

He spoke about the widths of the labyrinthine roads to be just wide enough to accommodate the trading vehicles needed and the way buildings form and function took into account the neighbours’ use and needs

![]()

Cadiz urban form, source: google maps

SHAPING CADIZ

The architecture and form of Cadiz of today is largely a legacy of the last 200 years. While the urban formation of the town dates back to Phoenicians of the 7th century BC, different periods of development were erased by conflict: the Roman settlement of Gades was raised by Visigoths in 410, and then in 1596 the Spanish Cadiz was destroyed by the British after the Spanish royalty refused to pay the demanded ransom. After this second destruction the medieval walls were demolished and a new militarised boundary was constructed, expanding the city limits to the whole of the peninsula, and it is these fortifications which forms the old town of today, enclosing the urban fabric that Eno so enjoyed on his holiday.

The city which grew became denser with a network of pathways through a compact architecture, and as global and American trade of the 18th century saw the economy grow the existing building stock was regularly updated through construction of new floors, facades and piecemeal expansion, evolving into the tightly packed urban structure of today. The redevelopments and increasing density was not a response to restriction of space within the city walls, but more the shifting needs of the harbour, trade and of all the inhabitants living conditions.

Though the Byzantine and Moorish settlements are long lost under the later destructions and developments, its trace remains, and not just in the etymology in its name, Gades to Qādis to Cadiz, but perhaps also in the approach to commons and urban space. Both Byzantine and Islamic approaches to urban development were codified in writings from 533 onward, with Julian of Ascalon’s treatise which was then absorbed and adapted into approaches from Islamic scholars. The codes were not rules as such, more guidance and ethics which were then adapted by local governing bodies with their particular vernaculars and practices, with legal systems also drawing from them as and when conflicts and disputes caused the codes to be written into frameworks as societies and cities developed. Julian of Ascalon’s underlying goal was:

Talking of architecture and how urban forms develop, he suggested “speculative things are likely built by dictators, but the things we love are built by many people banging into them”, suggesting that the generative processes of community and co-existence shape urban space through dialogue and evolution in a more human and endearing than top-down policy and free-market forces. He then mentioned a recent holiday in Cadiz, Spain, where he considered the tightly packed old-town core to have been shaped through care, an empathy and awareness of other city users.

He spoke about the widths of the labyrinthine roads to be just wide enough to accommodate the trading vehicles needed and the way buildings form and function took into account the neighbours’ use and needs

Cadiz urban form, source: google maps

SHAPING CADIZ

The architecture and form of Cadiz of today is largely a legacy of the last 200 years. While the urban formation of the town dates back to Phoenicians of the 7th century BC, different periods of development were erased by conflict: the Roman settlement of Gades was raised by Visigoths in 410, and then in 1596 the Spanish Cadiz was destroyed by the British after the Spanish royalty refused to pay the demanded ransom. After this second destruction the medieval walls were demolished and a new militarised boundary was constructed, expanding the city limits to the whole of the peninsula, and it is these fortifications which forms the old town of today, enclosing the urban fabric that Eno so enjoyed on his holiday.

The city which grew became denser with a network of pathways through a compact architecture, and as global and American trade of the 18th century saw the economy grow the existing building stock was regularly updated through construction of new floors, facades and piecemeal expansion, evolving into the tightly packed urban structure of today. The redevelopments and increasing density was not a response to restriction of space within the city walls, but more the shifting needs of the harbour, trade and of all the inhabitants living conditions.

Though the Byzantine and Moorish settlements are long lost under the later destructions and developments, its trace remains, and not just in the etymology in its name, Gades to Qādis to Cadiz, but perhaps also in the approach to commons and urban space. Both Byzantine and Islamic approaches to urban development were codified in writings from 533 onward, with Julian of Ascalon’s treatise which was then absorbed and adapted into approaches from Islamic scholars. The codes were not rules as such, more guidance and ethics which were then adapted by local governing bodies with their particular vernaculars and practices, with legal systems also drawing from them as and when conflicts and disputes caused the codes to be written into frameworks as societies and cities developed. Julian of Ascalon’s underlying goal was:

“…to deal with change in the built environment by ensuring that minimum damage occurs to pre-existing structures and their owners, through stipulating fairness in the distribution of rights and responsibilities among various parties, particularly those who are proximate to each other. This ultimately will ensure the equitable equilibrium of the built environment during the process of change and growth.”

The codes accepted that built places do change and evolve over time, but were about building in respect and empathy into the processes to ensure freedom, interdependence, commonality and to protect the public realm from degradation from activities in private spaces. The codes are particularly interested in the spaces where private and public meet, and this was also developed in the Islamic scholars through development of the idea of fina.

Residents cleaning their fina space, in a 1960s Cadiz provence town, Photo by Bernard Rudofsky.

Fina is an invisible area surrounding private property of 1 to 1.5 metres, surrounding the totality of a built form and particularly the boundary which directly addresses public streets and paths. Within this space the property owner has an extent of freedom but also responsibilities. The owner must keep the area clear of rubbish or hazards, but can use the space for functions which benefit the community, such as drinking troughs, benches or lighting. Equally, owners can build out into the space at higher level, resulting in the balconies and bridging across narrow streets. Public rights of way had to remain, and different localities used different measuring devices to determine the pathway clearance needed - from the height of a knight carrying weapons in one town, or a camel carrying goods in another, and fina operated as a threshold between private and public use, management and understanding of space.

Owners could build new floors on their buildings, so long as it did not encroach on others’ living or working conditions, and the codes provided a system for negotiation of these to benefit both the individual growth and the community cohesion and common spaces. The built form which results from these codes, and the approach of fina, is visible across Mediterranean towns, and the codes as guiding principles rather than dogmatic top-down instruction are thus flexible and have been absorbed into contemporary urban practices in the regions.

Academic Besim Hakim outlines Julian of Ascalon’s seven codes as:

- Change in the built environment should be accepted as a natural and healthy phenomenon. In the face of ongoing change, it is necessary to maintain an equitable equilibrium in the built environment.

- Change, particularly that occurring among proximate neighbours, creates potential for damages to existing dwellings and other yeses. Therefore, certain measures are necessary to prevent changes or uses that would (a) result in debasing the social and economic integrity of adjacent or nearby properties, (b) create conditions adversely affecting the moral integrity of the neighbours, and (c) destabilise peace and tranquillity among neighbours.

- In principle, property owners have the freedom to do what they please on their own property. Most uses are allowed, particularly those necessary for livelihood. Nevertheless, the freedom to act within one’s property is constrained by pre-existing conditions of neighbouring properties, neighbours’ rights of servitude, and other rights associated with ownership for certain periods of time.

- The compact built environment of ancient towns such as Ascalon necessitates the implementation of interdependence among citizens, principally among proximate neighbours. As a consequence of interdependence, it becomes necessary to allocate responsibilities among such neighbours, particularly with respect to legal and economic issues.

- It is desirable to maintain a built environment that will uplift the spirit of its inhabitants. Certain views should be preserved, especially those that give pleasure to the beholder or bear cultural significance. Making use of the bounties of nature within one’s property, such as collecting rainwater and planting fruit trees and vineyards, should be encouraged.

- The use of improved building materials and construction techniques should be encouraged, as their utilisation will reduce the burden of preventative setbacks from property boundaries and thus maximize the potentials of the land.

- The public realm must not be subjected to damages that result from activities or waste originating in the private realm, or from the placement of troughs for animals.

SHAPING THE CITY OF LONDON

Let’s compare this with contemporary, neoliberal London, and in particular the enclave of the City of London. The City, shaped by financial trading just as Cadiz was shaped by harbour trading, is also effectively a walled city. The boundaries of the City, which is governed by the City of London Corporation, a version of a council which is dominated by big business and exists somewhat outside of the laws and democratic structures which we are more used to in the rest of Britain.

Boundary of the City of London, Source: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/about-the-city/about-us

Boundary of the City of London, Source: www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/about-the-city/about-us

But it is tightly bounded by its invisible jurisdictional boundaries, and its rapid rate of growth since the emergence of neoliberalism as the dominant political process in the mid 1980s has been phenomenal. The market-forces codes of neoliberalism have shaped the built form of the City just as the codes that shaped Cadiz, but in a market-forces led system of individual power at the expense of the common or social there has been a desire for untethered growth and with little respect to neighbours, commons, community or any other beneficiary than the market and capital.

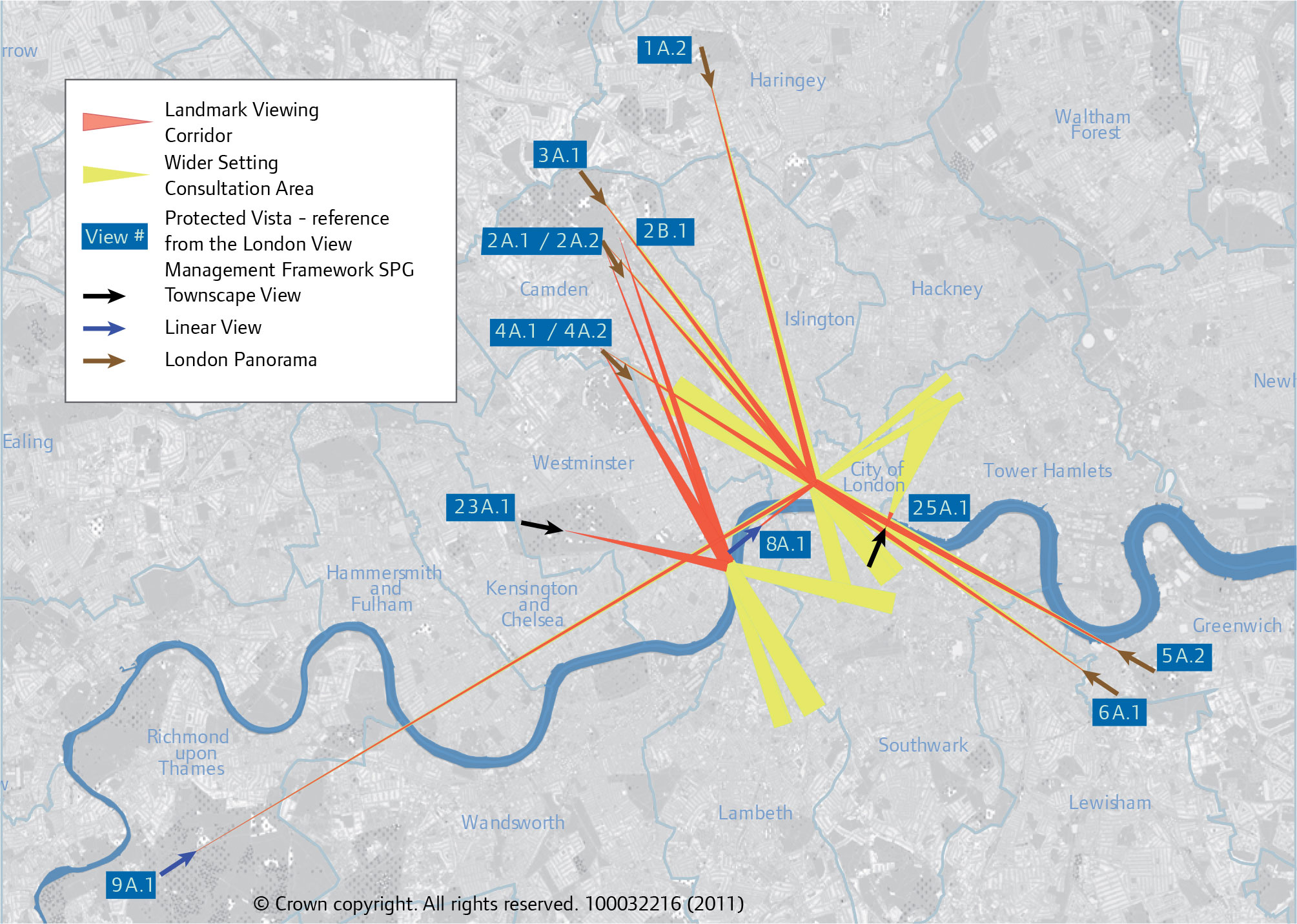

However, there are top-down rules which do enforce a shape upon the built form the neoliberal growth which expands the city. An example of this is the London Plan protected views and sightlines, particularly focused on vantages of St. Paul’s, the Palace of Westminster and the Tower of London. But these restrictions are not embraced as an ethical code of how urban form is shaped by designers, so much as a challenge to push to the limits or, where possible, get exemption from.

Protected sightlines in London, source: https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/planning/london-plan/current-london-plan/london-plan-2016-pdf

Two of these are the Leadenhall Building, nicknamed the Cheesegrater, a wedge shaped tower which took form from the need to minimise impact of cathedral views from Fleet Street and the Scalpel, currently under construction, with geometric wedges chiselled from its hulk in order to satisfy views of St. Paul’s. The very form of these developments is shaped by the maximum they can get away with within the regulations, and not with a generosity or communal good at heart, but maximum capital return.

Another top-down rule is Section 106, the regulation that developments must contribute in some way to better the community in which the building is located. More often that not, however, this is now played by the developer so that what is termed as “community” good benefits the private users of the building or its agenda more than the ideas of fina or social negotiation. Instead, we get the Sky Garden at the top of the Walkie Talkie which pretends it’s a public park while enforcing strict rules of access and having a primary function of offering expensive eateries with a view for corporate clients of the building’s inhabitants, or ground-level public realm offer like that of the Cheesegrater which really acts as a grand entrance lobby for the office workers than a community offer.

Neoliberal London takes these top-down rules and uses them to their advantage to increase capital or to function as a marketable asset, instead of in the generous, neighbourly and communal approaches developed from Julian of Ascalon’s codes, which developed into the form of Mediterranean towns such as Cadiz along with approaches like fina.

”Public” space at the base of the Cheesegrater, source: https://www.kone.co.uk/stories-and-references/references/122-leadenhall.aspx

”Public” space at the base of the Cheesegrater, source: https://www.kone.co.uk/stories-and-references/references/122-leadenhall.aspx

LEARNING

Eno has spent many years developing his ideas around generative music, a form of music making which is bounded by overarching rules and structure but without strict score or orchestration. No two performances of such generative music will be the same, though they will each be guided by codes which affect the overall form without dictating an absolute shape.

This is how Mediterranean towns, such as Cadiz, have developed. There is no top-down instruction to such walled-cities, but principles and codes which have offered a platform for common approaches and empathetic developments which provide the spaces that are needed for the commons as well as offering a mechanism for private growth.

In the City of London there is no generative approach to space or form. Instead we see whole areas demolished and rebuilt afresh every few decades, with huge environmental and social cost. This is what has happened at Broadgate with the destruction of the last of Peter Foggo’s celebrated boom office blocks now imminent, to be replaced just thirty years later by a much larger project in scale and rentable profit. The commons and public is always the most at risk from this approach of neoliberal urban development. When “community” is considered it is often semantically or physically skewed to the benefit of the private and the huge upheaval of demolition and rebuilding every few decades leads to a social fabric of constant trauma and absence, rather than a possible one of generative addition and evolution of form.

Perhaps the City needs more generative and empathetic thought in shaping the city, an idea like fina to think about the public offer within the totality of a project and not just as a plug-in to suit Section 106. Stavros Stavrides, in his recent book The City of Commons, writes at length about porous and threshold spaces to link and relate to the private and public. Common space is, he says, “produced through collective inventiveness”, which reminds of Julian of Ascalon’s “equitable equilibrium of the built environment during the process of change and growth”.

Where we have ceded all responsibility and decision to the dictator of the market, and not commons or community logic, and then have authoritative top-down regulations with the prime aim of trying to hold back the extent of the market’s physical form rather than create a platform for generative, participatory development, we end up with architectural forms as have emerged in the City of London. Architecture which takes its very form from maximising the marketable space within the limits set by regulations, such as sight lines of St. Paul’s, which acts as invisible mechanisms of making form and a line for neoliberal developers to push up against and test.

Eno discussed “the negotiation of making place”, though in the City the only real negotiation which exists is that between the private developer and their battle against top-down regulation. There is little negotiation with community, wider ethical principles, long-termism or a genuine interest in the third space of public/private thresholds. The fina and the threshold are both the spaces which give a city its civic, its public and its individuality. As the negotiation space between public and private it is also the space of of politics. This is the space that private expands into, gives back or plays with in a participatory construct. In neoliberal London, where market forces dictate value, function and control, there is less negotiation between public and private and more gameplaying by private as it endeavours to claim and organise the public in its own image and to its benefit. What if all buildings in the City of London, instead of playing the Section 106 game, had to introduce a fina of 4 metres around all of its building, a space that was given to public use, nature, ecology and accident. And what if corporations and developers who see more value in destruction to create a tabula rasa to build again, instead consider value in terms of commons, generative building and dialogue.

Further Reading:

Barau, A. Integrating Islamic Models of Sustainability in Urban Management: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262689503_Integrating_Islamic_Models_of_Sustainability_in_Urban_Spatial_Planning_and_Management

Eno, B. And Chilvers, P. Generative Music apps: http://www.generativemusic.com/

(https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/oct/31/corporation-london-city-medieval target="_blank">www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/oct/31/corporation-london-city-medieval)

Hakim, B. Julian of Ascalon’s Treatise of Construction and Design Rules from Sixth-Century Palestine.: https://www.jstor.org/stable/991676

Hakim, B. Mediterranean Urban and Building Codes: Origins, Content, Impact, and Lessons: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1057/udi.2008.4

Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/public-purpose/

Monbiot, G. The Medieval, Unnacountable Corporation of London is Ripe for Protest: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2011/oct/31/corporation-london-city-medieval

Public Practice: http://www.publicpractice.org.uk/

Verdejo, J., Arcas, J. And Funo, S. Considerations on Urban and Block Formation of the Old Quarter in Cadiz: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/aija/80/713/80_1557/_pdf

Wainwright, O. And Ulmanu, M. ‘A Tortured Heap of Towers’: The London Skyline of Tomorrow: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/dec/11/city-of-london-skyline-of-tomorrow-interactive