Black mirror crack’d

Essay2020

Essay looking into the meanings & meanderings of the cracked mobile phone screen.

The Culver Hotel, ©Will Jennings

I recall the precise moment.

I was standing by the road in Culver City, gazing towards the hotel where Munchkins spent the evenings of eight weeks filming The Wizard of Oz in debauched parties, orgies and drunken violence. When they were regularly called, the police tried to catch the actors with butterfly nets, before finding their handcuffs were simply too large for the perpetrators’ wrists with the apprehended slipping free to continued chaos.

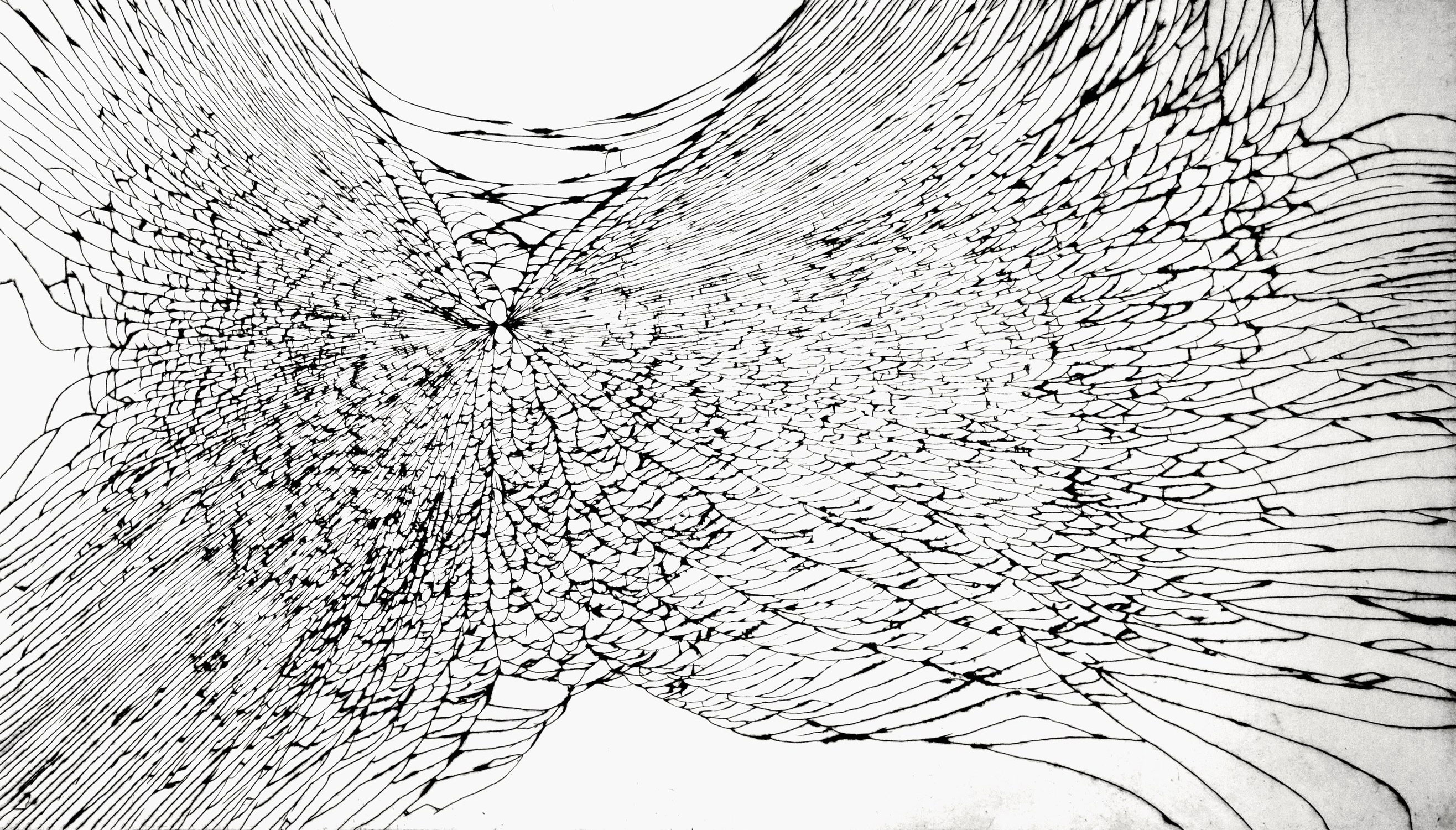

I stood with two bags of luggage picturing these scenes in my mind, when my Uber suddenly appeared. Shocked out of my daydreaming I reached down to grab my bags and dropped my mobile phone, watching it descend in slow motion as the corner made contact with the concrete sidewalk. In one movement, I retrieved it from the ground and moved towards the car, glancing at my phone to notice an apparent new topology had been cast across the city map of the app - what looked like lanes and new paths ruptured the rigid LA grid. My screen was cracked, the hairlines spreading from bottom left corner reaching to the top right. The under-glass image now disrupted and interrupted, forcing me to change the way I interpreted the glowing information.

Using it felt different too. What was before a smooth swipe, a brushing of my flesh across the surface of glass now quickly made my fingertip sore. The tiny crevices were causing discreet lacerations, tiny fingerprint alterations with each app refresh and message typing. There seemed a direct correlation between my physical and digital self, I would think twice before starting to reply to thatemail because of a slight desire to let my index finger momentarily recover.

Our fingertips contain thousands of nerve endings, densely packed1 to read subtle shifts of pressure and contact, and in turn feed that constant flow of information to our own brain to programme gesture, control, balance and grip. Along with the forehead, they are the part of our body most sensitive to pain,2 which would be why my own tips began to ache as I sat in the taxi checking twitter as I headed towards LAX.

A lot of things have happened, ©Sam Hodge

The relationship between you and your screen doesn’t stop at the haptic and visual, there is an exchange taking place every time you push your flesh to it. The surface of the glass is coated in a conductive material, such as tin oxide, which acts as a capacitor storing constant small electrical charges. When your salty and moist skin makes contact the capacitor discharges, you suck the electrical charge from it, completing the circuit, the machine becomes part of you. As electricity micro-surges into your finger, the drop in voltage within the oxide skim is then read by the processor to determine where your gesture was cast. As meat connects with silicon, you and machine temporarily become one.

A screen shatter prevents this. As the glass cracks, so does the conductive surface. It is not only the smoothness of that surface which is lost once you drop your phone to the hard ground, but also the very smoothness of transaction, and so to does the implicit connection between you and it facilitated by that frictionless relationship.

Clickbait websites provide short lists of reasons why you should immediately STOP using your smashed screen and replace it with a pristine facade. These include the obvious such as “the crack could get worse”, through to the phone eventually failing to work, and that it could be a road hazard due to the loss of map clarity if using your phone as navigation device.

The lists also include health. My sore fingers were testament to the physical damage that can occur with a broken screen, but they suggest it a far riskier activity. The cracked screen, they declare, harbours germs, bacteria and a million possible illnesses. You go to the toilet, press a road crossing button, grasp door handle after handle, your day is spent collecting germs, all these activities interspersed with grabbing your phone and swiping up, down, left, right.

Every timeline refresh embedding more germs into the storage cracks of your broken screen. Each loving text to your partner compressing future disease into your device. In the clickbait warnings, your phone becomes a portable vitrine of viruses, repository of intermingling germs waiting to attack. The phone rings, and in one movement you answer the call, hold it to your face, and push poison to your cheek. Creating germ passage from glass cracks into shaving cuts and pores. The health risks go even greater than disease:

The Nation.com3

The concern here that damage to health, however bad, as something tied to capital and potential cost, rather than personal wellbeing, speaks perhaps of American and other non-NHS audiences who may read the articles, but also to the late-capitalist way in which all action only relates to the financialrather than any other value system. It’s near-impossible for any new object in our world to exist outside of the capitalist system, but the way that the mobile phone, and the web we reach through it, has co-opted the language, structures and financial models of all that was beginning to crumble in the physical world is astonishing.

As well as the new industries of phone insurance, protection, tiny streetside one-man start-ups specialising in phone repairing, and the culture of needing to buy the newest and shiniest, capital transaction has become the very daseinof the digitised world. With cyberspace now secured behind algorithms, legal division, paywalls and apps, we are secluded in bubbles, and a cyber-landscape that could have become anarchic state of freedom and experiment has slowly adopted the form and language of the built and capitalist structures which shape and contort our collective and individual beings to their whim.

The Nation.com4

Though these lists don’t mention seven years bad luck (a superstituous tale likely started to scare clumsy servants from breaking expensive mirrors in the 15th century) they do offer one unexpected health risk: nomophobia. Defined as “the fear of not being able to use a… mobile phone and/or the services it offers”, with the loss of “connectedness” and “information” that smart phones provide,5 it illustrates that in just a decade this device has become a critical addition to our being to such an extent that when our normal use is prohibited it is as if a part of our very identity has malfunctioned, our cyborg self-disabled.

Now Sol’s Samsung is worthless, ©Sam Hodge

In 1982 James Wilson and George Kelling published an article, Broken Windows,6 in which they presented their theory that small but visible acts of vandalism or crime present signs of an urban decay that can lead to increased disorder, including serious crime. It was adopted by 1990s New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani and police commissioner William Bratton. They took a strong stance upon petty misdemeanours such as pissing in public, fare evasion, graffiti and traffic-jam squeegee men, with a very public zero-tolerance policing which was then adopted by Jack Straw and Tony Blair before Bratton was even approached to head up the MET by David Cameron in 2011.

Wilson & Kelling, 19827

This idea that broken glass, even a crack, will slowly grow over time and can be read as a harbinger of greater social ill, which we see in the Broken Windows theory as well as the clickbait lists that claim your economic and social worth is perceived to be lower if people see your broken mobile screen, shows that appearance and pristine smoothness is built into neoliberal models of value and order. In a culture of commodity, the things in the world which we shape - whether building or telephone - are a public presentation of our very self, and that our worth is intricately tied up in that perception of self. In a world of image and presentation, a crack is not just a crack, it is a public declaration of failure and impending decay.

Baudrillard8

Los Angeles’ Bonaventure Hotel, designed by John Portman, is the go-to example of late-capitalist postmodern architecture for theorists, analysed by Jean Baudrillard, Edward Soja,9 Frederick Jameson10 and Mike Davis11 amongst others, and used across culture from Buck Rogers to Mission Impossible, Usher to Grand Theft Auto V12. Three cylindrical tubs of mirror glass bounces back the image of the city, in the urban but apart from it, the inside can see out but the outside only sees itself. The external appropriated for the gaze of the internal, but withholding the return gesture.

The Grand Theft Auto V simulacra of the Bonaventure Hotel

The glazing refracts back a representation of the real and tightly encloses an alternative city with all the functions a particular consumer would need, withdrawn from external messiness. It sits within concrete LA as a perfect totality, foreshadowing the 2007 appearance of the sleek, polished iPhone into the beige world of electronics. The external reflective smoothness of both Bonaventure and iPhone symbolised their powerful objectness, tightness of form and function with beguiling majesty.

Smoothness gives a sense of ease of use and movement. A person can be smooth, socially adept with skilful interaction towards their prey. Smooth traffic aids commutes along urban arteries. Smooth music is unchallenging. A smooth sea offers safe passage. Waxed smooth bodies promote clothes, perfume and material goods on billboards. Smooth business and political dealings emit the appearance of polite dialogue towards the pretence of a shared desired outcome.

And that which is not smooth, such as actual tangled complexities of politics, are presented by media and protagonists as simple, succinct, smooth sound bite lumps:

STRONG AND STABLE

LEAVE MEANS LEAVE

THE PEOPLE

SPOKE

GET BREXIT DONE

CONTROL THE VIRUS

CHECK CHANGE GO

BUILD

BUILD BULD

Polished nuggets of nothingness that exist in place of complexity, courseness, and roughness of reality. So is it any wonder that the objects we make reflect this zeitgeist? Whether that be mobile phones or city buildings.

It works, which is the main thing, ©Sam Hodge

Urban centres are complex places, incrementally tweaking over hundreds of years with a myriad of owners, occupiers and interests. The architecture and urban fabric itself develops piecemeal, buildings interact with one other in complicated ways, passageways remain, materiality adjuncts, and this creates awkwardness and complication as well as joyous juxtapositions and in-between spaces.

Cracks in the urban are critical, they both illustrate the enormous bundle of interactions and desires that the city represents, but also physically offer the spaces that allow for new forms, growth and community to develop. Small pockets of railway arches where Nollywood DVD sellers squeeze their body and stock. Accidental undercrofts skateboarders discover and develop their artistry around. Abandoned pieces of council land at traffic junctions that local residents guerrilla garden.

But as with other objects and systems we shape ourselves to, the city form is rapidly becoming smoother, polishing the rough and building out possibility of uses and social functions that such spaces permit. QUANGOs take ownership of swathes of urban space, keeping it nice, clean, controlled and commodified for consumers, not complex and real for citizens.13 The city is increasingly planned by developers and investment funds with a primary interest in financial return over places people need or can adapt, cracks repaired.

Neo Bankside, © Will Jennings

Glass is a go to material for so many of the speculative developments favoured in such projects, wipe clean and glowing, offering vast views over the city for those with the money.14 In 1933, Walter Benjamin pronounced glass as the modern material which could open up a new humanity, “Objects made of glass have no aura. Glass is, in general, the enemy of secrets. It is also the enemy of possession.”15

But what we find is that in reality glass offers a safety barrier for financial institutions, political players and penthouse occupiers which presents the image of openness but is as impenetrable as concrete. The smooth glass surface of our technological age acts as the barrier to concealment, and it has become the material of luxury possession, and Benjamin’s hopes of a traceless existence now seem unobtainable as the glass technology we carry with us remembers every residue of our existence.

Extinction Rebellion protestor, ©AFP

At the 2019 Extinction Rebellion protests in London there was an unusual air of politeness from the activists. They used non-violent forces to make their position known, covered Waterloo Bridge in trees and plants, and at the end of the campaign swept the streets clean leaving them tidier than when they arrived. However, there was a single instance of physical attack when windows of the Shell HQ on the South Bank were strategically smashed, not to gain illegal entry or as mindless vandalism, but as a strategic and symbolic fracturing of the surface of a corporate entity which rests its reputation on that seemingly transparent boundary between external image and internal reality.

2010 student protests front pages & wider angle image, photo ©AP

In riots it is the smashed window which attracts the attention of newspaper picture editors,16 a crowd of photographers crowding around a single aggressor as they hammer window with brick. At once an obvious symbol but also offering aesthetic beauty, the cracks emitting from point of impact offering a ready-made punctum to the photo. No other depth of meaning is necessary, a message with as much direct force as the action precipitating it.

![]()

Fisher17

Over the last decade the capitalist tentacles have extended their reach not by finding new external territories but internal, facilitated at increasing pace by our physical and emotional attachment to the mobile phone. We now know the level at which our data and personality is being harvested, not only mapping every step we take but also computing why we pause at locations, assessing the speed at which we look at online images, recording even text we delete as our mind changes, every refresh, swipe left or right.

We now exist in a surveillance capitalism where we are not just watched over by street CCTV but the tool we have invited into our lives, psyche and pockets. In the age of the algorithm we are not only watched but also predicted, turning our very essence of existence into an exploitable commodity, questioning notions of our free will. The smooth reflectivity of the phone gives sublime innocence to something more sinister, and we don’t really know what creature is listening or watching from other side. If we stare at our black mirror and say Zuckerberg five times, might he come out through our phone to attack us?

Sixteenth century occultist and astronomer John Dee owned an Aztec hand mirror of polished obsidian, a jet-black surface for the summoning of spirits and knowledge which also offers the holder to see their dark reflection looking back. By the late 1700s, as the romantic picturesque emerged as a dominant cultural aesthetic, black reflective mirrors became a popular tool of the day. Named after landscape painter Claude Lorraine, the user stood with their back to a natural scene and gaze into the Claude Glass. What they saw was a softened and framed vantage of the view with a simplified tonal range of painted quality, painting from this reflected view rather than the actual.

![]() John Dee’s obsidian mirror at the British Museum, ©Universal Images Group

John Dee’s obsidian mirror at the British Museum, ©Universal Images Group

Today, we stare into our own black mirrors, swiping through Instagram filters and Snapchat lenses, with a similarly transmogrified and unrealistic view of reality, casting into it for spiritual advice. When turned off, our own dark selves stares back, deeper embedding the psychological belief that this simple, small object is a part of us. We see our face, it is me, we are one. When we stroke our fingers over the screen there is no friction. It is like stroking a loved one, the morning light shimmering off their body as they lay beside us. But the other here is an extension of the ego, a masturbatory stroke further penetrating the physical self into the digital.

When this glass breaks, we are reminded of the periphery between our truth and reflected simulacrum. The splits in the screen turn reflection to refraction, the self we now see looking back surreal and upset, Picasso-esque fractured identity. And our touch is disrupted. Instead of the fusing of finger and glass perfectly bonding organic and silicon, we are made aware of the unreality of the relationship, the fragility of that connection and the shallowness on which it is built.

If global superstitions around mirrors are rooted in reflection offering a pathway between the real world of man and spiritual world of the gods, then the breaking of the reflective object rips asunder that connection. But if the gods of the age are digital behemoths and ever-watching eyes of capitalist overlords, then perhaps this disruption is not one to be superstitious about, but to be celebrated as an act of rebellion.

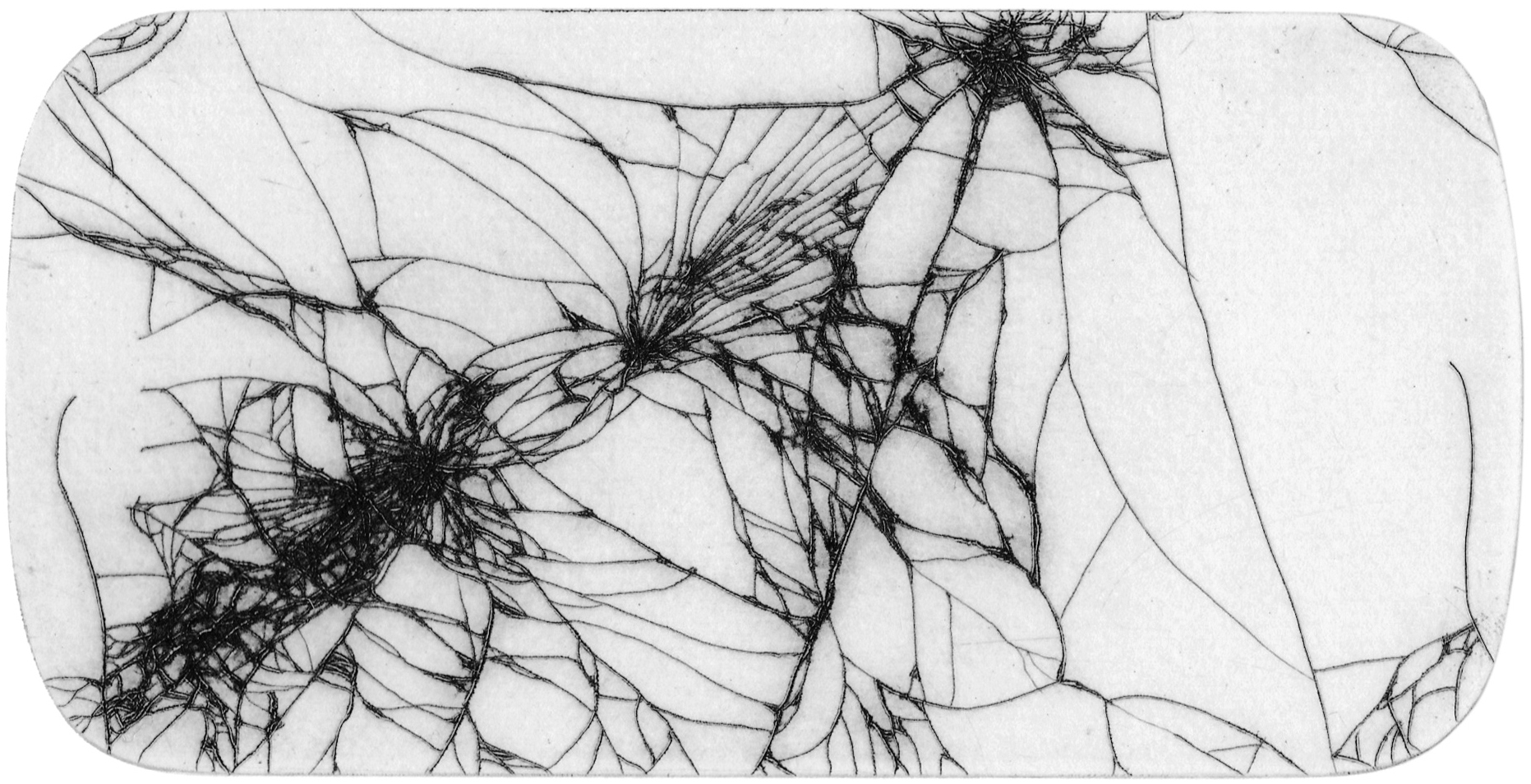

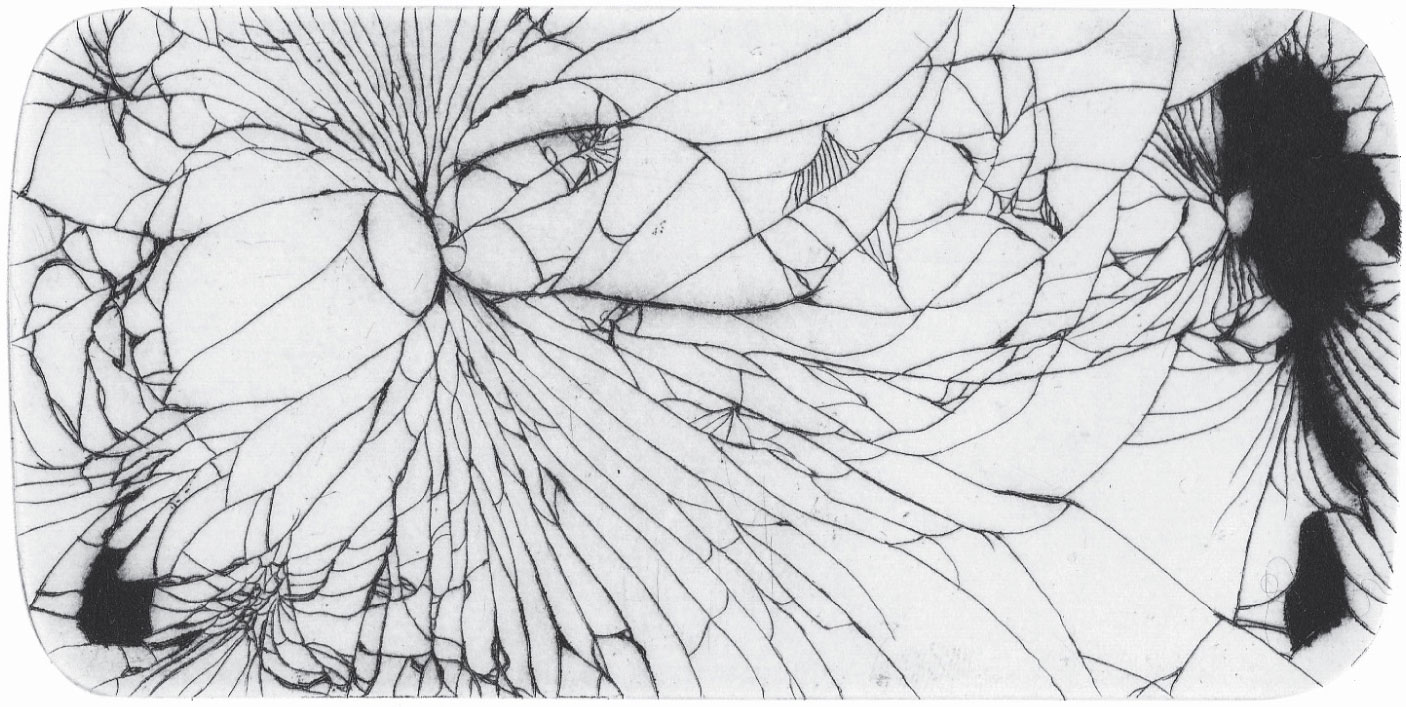

Marcel Duchamp took pleasure from the aesthetic dafter two of his glass works broke. 1918’s To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour cracked in transit X, while both glazed panels of his celebrated 1915-23 The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) are fractured, the artist repairing them with lead wire and varnish X in an act of kintsugi, recognising and celebrating the flaw as an element of story. No two cracks will ever be the same, and they act as an abstract index of the angle of collision and material of impact. In its own way, the crack pattern is a unique work of art, so perhaps it’s no wonder that Duchamp felt it added a surreal addition to his tightly organised glass sculptures.

![]()

To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour, ©MoMA

Though now I know that people seeing me using my smashed phone may think less of me as a human being and that I am not serious about my career, like Duchamp I take some comfort from my small broken glass. When I stroke my index finger across the screen it may make me a little sore, but I am in a tiny way reminded of my meatness and humanity. It alludes to the fact that the data I am looking at - whether photo, map or information - is just a representation, and the truth and belief in it is as fragile as the screen I have smashed. Perhaps these tiny breaks in millions of screens across the world are just symbolic hairline fractures of a much larger structural chasm to come.

It feels slightly transgressive to continue using it over a year after it cracked, that in some way I am disrupting the system of obsolescence and easy transaction. I know this transgression is just psychological gesture, but it feels meaningful as my finger passes the glass fragments. It reminds me after a while to put it down, and exist in airspace rather than cyberspace, and just as the cracks themselves are a memory of trauma embedded into uniform capitalist object, I am given brief reminiscence of that end to a pleasurable holiday, with Munchkins avoiding arrest.

![]()

There was someone watching Alanna who saw the whole thing, ©Sam Hodge

With thanks to Sam Hodge for the use of her series Shattered.In riots it is the smashed window which attracts the attention of newspaper picture editors,16 a crowd of photographers crowding around a single aggressor as they hammer window with brick. At once an obvious symbol but also offering aesthetic beauty, the cracks emitting from point of impact offering a ready-made punctum to the photo. No other depth of meaning is necessary, a message with as much direct force as the action precipitating it.

Fisher17

Over the last decade the capitalist tentacles have extended their reach not by finding new external territories but internal, facilitated at increasing pace by our physical and emotional attachment to the mobile phone. We now know the level at which our data and personality is being harvested, not only mapping every step we take but also computing why we pause at locations, assessing the speed at which we look at online images, recording even text we delete as our mind changes, every refresh, swipe left or right.

We now exist in a surveillance capitalism where we are not just watched over by street CCTV but the tool we have invited into our lives, psyche and pockets. In the age of the algorithm we are not only watched but also predicted, turning our very essence of existence into an exploitable commodity, questioning notions of our free will. The smooth reflectivity of the phone gives sublime innocence to something more sinister, and we don’t really know what creature is listening or watching from other side. If we stare at our black mirror and say Zuckerberg five times, might he come out through our phone to attack us?

Sixteenth century occultist and astronomer John Dee owned an Aztec hand mirror of polished obsidian, a jet-black surface for the summoning of spirits and knowledge which also offers the holder to see their dark reflection looking back. By the late 1700s, as the romantic picturesque emerged as a dominant cultural aesthetic, black reflective mirrors became a popular tool of the day. Named after landscape painter Claude Lorraine, the user stood with their back to a natural scene and gaze into the Claude Glass. What they saw was a softened and framed vantage of the view with a simplified tonal range of painted quality, painting from this reflected view rather than the actual.

John Dee’s obsidian mirror at the British Museum, ©Universal Images Group

John Dee’s obsidian mirror at the British Museum, ©Universal Images Group

Today, we stare into our own black mirrors, swiping through Instagram filters and Snapchat lenses, with a similarly transmogrified and unrealistic view of reality, casting into it for spiritual advice. When turned off, our own dark selves stares back, deeper embedding the psychological belief that this simple, small object is a part of us. We see our face, it is me, we are one. When we stroke our fingers over the screen there is no friction. It is like stroking a loved one, the morning light shimmering off their body as they lay beside us. But the other here is an extension of the ego, a masturbatory stroke further penetrating the physical self into the digital.

When this glass breaks, we are reminded of the periphery between our truth and reflected simulacrum. The splits in the screen turn reflection to refraction, the self we now see looking back surreal and upset, Picasso-esque fractured identity. And our touch is disrupted. Instead of the fusing of finger and glass perfectly bonding organic and silicon, we are made aware of the unreality of the relationship, the fragility of that connection and the shallowness on which it is built.

If global superstitions around mirrors are rooted in reflection offering a pathway between the real world of man and spiritual world of the gods, then the breaking of the reflective object rips asunder that connection. But if the gods of the age are digital behemoths and ever-watching eyes of capitalist overlords, then perhaps this disruption is not one to be superstitious about, but to be celebrated as an act of rebellion.

Marcel Duchamp took pleasure from the aesthetic dafter two of his glass works broke. 1918’s To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour cracked in transit X, while both glazed panels of his celebrated 1915-23 The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass) are fractured, the artist repairing them with lead wire and varnish X in an act of kintsugi, recognising and celebrating the flaw as an element of story. No two cracks will ever be the same, and they act as an abstract index of the angle of collision and material of impact. In its own way, the crack pattern is a unique work of art, so perhaps it’s no wonder that Duchamp felt it added a surreal addition to his tightly organised glass sculptures.

To Be Looked at (from the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour, ©MoMA

Though now I know that people seeing me using my smashed phone may think less of me as a human being and that I am not serious about my career, like Duchamp I take some comfort from my small broken glass. When I stroke my index finger across the screen it may make me a little sore, but I am in a tiny way reminded of my meatness and humanity. It alludes to the fact that the data I am looking at - whether photo, map or information - is just a representation, and the truth and belief in it is as fragile as the screen I have smashed. Perhaps these tiny breaks in millions of screens across the world are just symbolic hairline fractures of a much larger structural chasm to come.

It feels slightly transgressive to continue using it over a year after it cracked, that in some way I am disrupting the system of obsolescence and easy transaction. I know this transgression is just psychological gesture, but it feels meaningful as my finger passes the glass fragments. It reminds me after a while to put it down, and exist in airspace rather than cyberspace, and just as the cracks themselves are a memory of trauma embedded into uniform capitalist object, I am given brief reminiscence of that end to a pleasurable holiday, with Munchkins avoiding arrest.

There was someone watching Alanna who saw the whole thing, ©Sam Hodge

- Johansson, Roland & Flanagan, J. “Coding and Use of Tactile Signals from the Fingertips on Object Manipulation Tasks”, inNature Reviews, Neuroscience, vol.10, 345-350, May 2009.

- Mancini, Flavia, Bauleo, Armando, Cole, Jonathan et al. “Whole-Body Mapping of Spatial Acuity for Pain and Touch”, in Annals of Neurology, 2014 Jun; 75(6):917-24. Epub 2014 Jun 6.

- The Nation. 5 Reasons You Should Fix Your Cracked Phone Screen, undated. Available at: https://www.nation.com/5-reasons-you-should-fix-your-cracked-phone-screen/

- Ibid.

- Yildirim, Caglar, "Exploring the dimensions of nomophobia: Developing and validating a questionnaire using mixed methods research" (2014). Iowa State University Capstones, Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 14005.

- Wilson, James & Kelling, George. “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety”, in The Atlantic Monthly, March 1982.

- Ibid.

- Baudrillard, Jean. America. Verso: London, 2010, p.62

- Soja, Edward. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. Verso: London. 1989, pp.243-244

- Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Duke University Press: Durham. 1991. pp.39-44

- Davis, Mike. “Urban Renaissance and the Spirit of Postmodernism”, in New Left Review, 151, May June 1985.

- See Colin Marshall’s compelling montage of 27 films featuring the Bonaventure: https://vimeo.com/140975476Se

- See Minton, Anna. What kind of world are we building? The privatisation of public spaceRoyal Institute of Chartered Surveyors: London. Available at: https://www.annaminton.com/single-post/2016/05/03/What-Kind-of-World-are-We-Building-The-Privatisation-of-Public-Space

- Heathcote, Edwin. “The Right to a View: Glass, Class and our Transparent Lives”, in The Financial Times, Oct 28, 2016. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/f082580c-960e-11e6-a1dc-bdf38d484582

- Benjamin, Walter. “Experience and Poverty”, in Die Welt im Wort, Prague. Gesammelte Schriften, II, pp.213-219. Trans. Rodney Livingstone.

- See this essay for a consideration of how glass is targeted in riots and protest: Crinson, M. “Glass Architecture - A Riotous Mythology”, in Metamute, 9 Feb 2012. Available at: http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/glass-architecture-%E2%80%93-riotous-mythology

- Fisher, Mark. Capitalist Realism. Zero Books: Alresford, Hants. 2009, p.8