Chartism & neoliberalism: Parallels between social conditions of the early 18th & 21st centuries

Essay2017

Britain in 2017 is in a place of turmoil and doubt arguably unrivalled since the years following the second world war. Many words are written and time is spent to analyse the issues and problems of the day along with potential futures or how the public may affect that future. However, the issues of now are frequently only compared against events immediately prior or, at best, to those of recent modern history, only assessing incremental and relative change.

As any historian knows, it can be prudent to extend the reach of thought deeper into the past. Not because, as the adage goes, history repeats itself but because of the proposition, attributed to Mark Twain, that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes”. It is with this approach that this paper considers the early 19th century Chartism movement in the United Kingdom, and specifically London, to consider the relationship between the politics of our neo-liberal circumstances and those of 200 years previous. I will draw parallels between the social ills which directly led to political uprisings, of which Chartism was the most organised and widespread movement, and the issues affecting us in 2017.

This paper does not offer solutions to the current predicament, but by holding up a candle to our past experiences seeks to explore a time of similar experiences with a hope that with this rhyme of them new paths can be plotted.

THE SOCIAL CONTEXT OF CHARTISM

Before delving into what Chartism was, the methods it utilised for political change and any comparisons with 21st century neo-liberal politics, it is important to understand the social and political context which forged the movement and the political events around it.

The summer of 1780 witnessed the Gordon Riots. The largest civil disobedience London had experienced lasted a week and led to hundreds being killed by being shot by the army or drowning in the river at Blackfriars, with a further 200 wounded and 450 arrested. Initially triggered by a fear of rising Catholicism following the 1778 Papists Act the events began after Lord Leigh Gordon, head of the Protestant Association, marched from St. George’s Fields in Southwark with huge crowds to deliver a petition against the act. The mass came upon Parliament at the same time as members of the House of Lords were arriving to debate and the anger of the crowds was tipped over into “manhandling” the lords and demolishing their coaches (German, R. and Rees, J., 2012, loc. 1733).

The riots, which continued for the following week, became less about religion and more about class with attacks on property of the elite, industrialists, aristocrats and judges as well as assaults upon Newgate Prison, the Bank of England and tollbooths on Blackfriars Bridge. German. R, and Rees, J. state (2012, loc. 1783) that the riots “were the doing of large numbers of working and poor Londoners, driven to these actions by a combination of identification of Catholicism with reactionary sections of the ruling class, class resentment, and hostility to changes in the way the city was organised”.

Thomas Paine published Rights of Man in 1791, a defence of the French Revolution and argument that popular uprising is allowable should a government not safeguard the basic rights of its population. Deliberately printed cheaply and easily distributed, up to 200,000 copies were sold over the first three years to an eager audience of working class people from Cornwall to Scotland. The French Revolution of 1789–99, to which Paine was writing in response, unnerved the British ruling classes and gave energy to the citizens demanding domestic reform.

An extension of an income tax, with exemption for the lower waged, which had been put in place as a temporary measure to cover the Napoleonic wars, was proposed by the Tory government in 1815. The nation had a burden of vast national debt of over £800m and it was argued by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nicholas Vansittart, that this “would be less burthensome than those taxes on consumption” (Vansittart, 1816).

Several petitions were sent to parliament opposing the extension from the kinds of groups, including landowners and businessmen, who were normally loyal to Westminster. The grandest of these was from the City of London Corporation, presented in person by the Sheriffs of London in full ceremonial robes, which Hansard reported thus:

“the manufacturing and trading interests are… depressed, and equally borne down with the weight of taxation… and they confidently hoped, that by such reductions in the public expenditure… and the abolishing of all unnecessary places, pensions and sinecures, there would have been no pretence for the continuation of a tax subversive of freedom, and destructive of the peace and happiness of the people.” (City of London Corporation, 1816).

When in March 1816 the government motion to renew income tax was defeated the commons erupted in “loud cheering which continued for several minutes” (Milleris, 2016). Consequently, the national debt, in effect loans to government from the richest of society, was repaid from inflated indirect taxation which fell more proportionately upon the poor.

1815 saw the first Corn Laws brought in by Tory politicians, predominantly land-owners, who sought to protect their own interests by artificially keeping the cost of their corn high through levying taxes on imported wheat. However, these were opposed by the Whigs who predominantly represented the new-moneyed industrial classes who would earn greater profits through keeping payments to factory workers low. Higher price for wheat meant low wages were not comparable to the rising costs of living fend off civil unrest from the lower classes employment conditions began to change so workers could be hired per day instead of annually, or as historian Katrina Navickas states, “the introduction of a type of zero-hours contract” (Prickett, 2016).

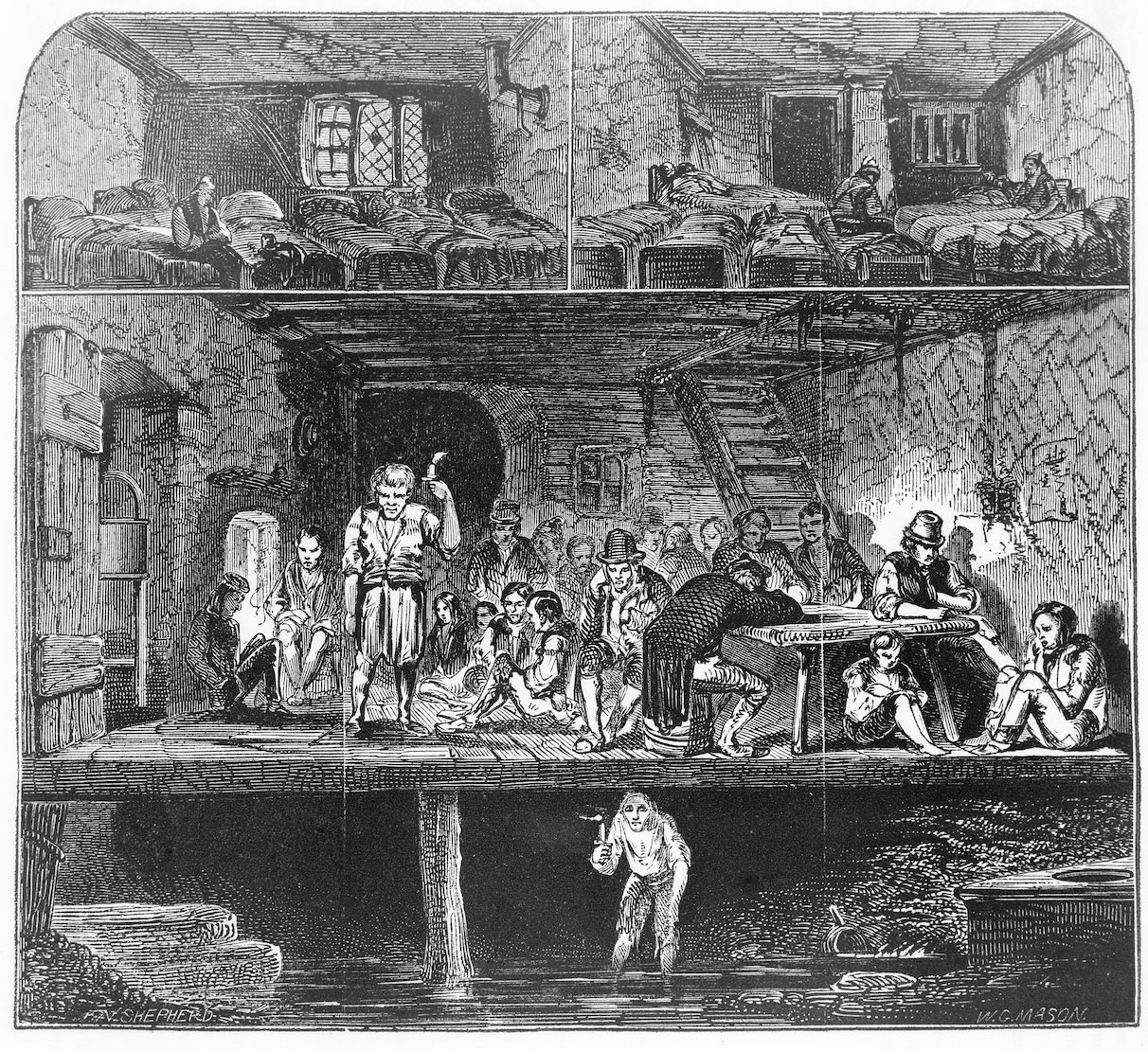

In the same year the Poor Law was introduced, ordering parishes to care for those who were unable to work. Taxes for this were raised from middle class and richer citizens, though there was opposition from those who said they disliked supporting the lazy and undeserving. An 1832 Royal Commission led to the 1834 Poor Low Amendment Act which determined the structures were expensive, wasteful and not sufficient to address abuse of the system. The primary mechanism of the amendment was “less eligibility”, stating conditions in workhouses must be worse than those outside so that only the truly desperate would apply for support. This was coupled with the second main mechanism, that Poor Law support was only granted to those in the workhouses so poorly paid labourers could not receive support as a ‘top-up’ to their wages. The opposition to the amendment was huge across the whole country, particularly in the North, and conditions in several workhouses were found to be dangerous and inhumane.

Conditions in many homes were equally as bad; Henry Mayhew writing in London Labour and the London Poor (1861) wrote that cellars were being rebranded as “ground floors” with a dozen people living and working in rooms twelve feet by eight, cellars that Engels described in The Condition of the Working Class in England as frequently “so inundated that the water has to be pumped out by hand” (1845, p. 72).

A Fictional Slum, (Gavin, H., 1848)

A Fictional Slum, (Gavin, H., 1848)

The amendment act was a point of protest for the next two decades and is a primary ingredient for the rapid rise of Chartism during the late 1930s. The amendment act was also significant in the emerging break between the working and middle classes, Bronterre O’Brien writing in 1836 wrote in the Twopenny Dispatch:

“In one respect the New Poor Law has done good. It has helped to open the people’s eyes as to who are the real enemies of the working classes. Previously to the passing of the Reform Bill, the middle orders were supposed to have some community of feeling with the labourers. That delusion has passed away.” (quoted in Thompson, 1984, p. 35)

Environmental and health conditions were also deteriorating. As well as sewerage flooding into overcrowded property, air pollution was filling the city causing people to get lost in darkness. With a population of over 1.6 million, during winter one could barely see to the end of a street so thick was the air with soot (German and Rees, 2012, loc. 1943). Vested interests fought against reforms to cleanse the air and water, as Moore (2016, p. 111) points out “opponents of clean water, as with climate change deniers, had their useful idiots in the educated press… to make a bogus case”.

Enclosure acts were removing access to “common” lands which had been under collective control of local people and “waste” lands which were not claimed by any group and open to cultivation by landless peasants. These acts had been passed increasingly since the 17th century but it was the act of 1773 which pushed the process further than any before, enabling landowners to increase tenants’ rent. As with the Poor Law, arguments were made against Enclosure stating it was the richer, connected landowners who always came out on top:

“A typical round of enclosure began when several, or even a single, prominent landholder initiated it… by petition to Parliament.… The commissioners were invariably of the same class and outlook as the major landholders who had petitioned in the first place, it was not surprising that the great landholders awarded themselves the best land and the most of it, thereby making England a classic land of great, well-kept estates with a small marginal peasantry and a large class of rural wage labourers.” (Stromberg, 1995)

The act was a large instigator into the migration of populations into the cities which coincided with urban factory owners being able to squeeze lower wages from an enlarging pool of urban poor.

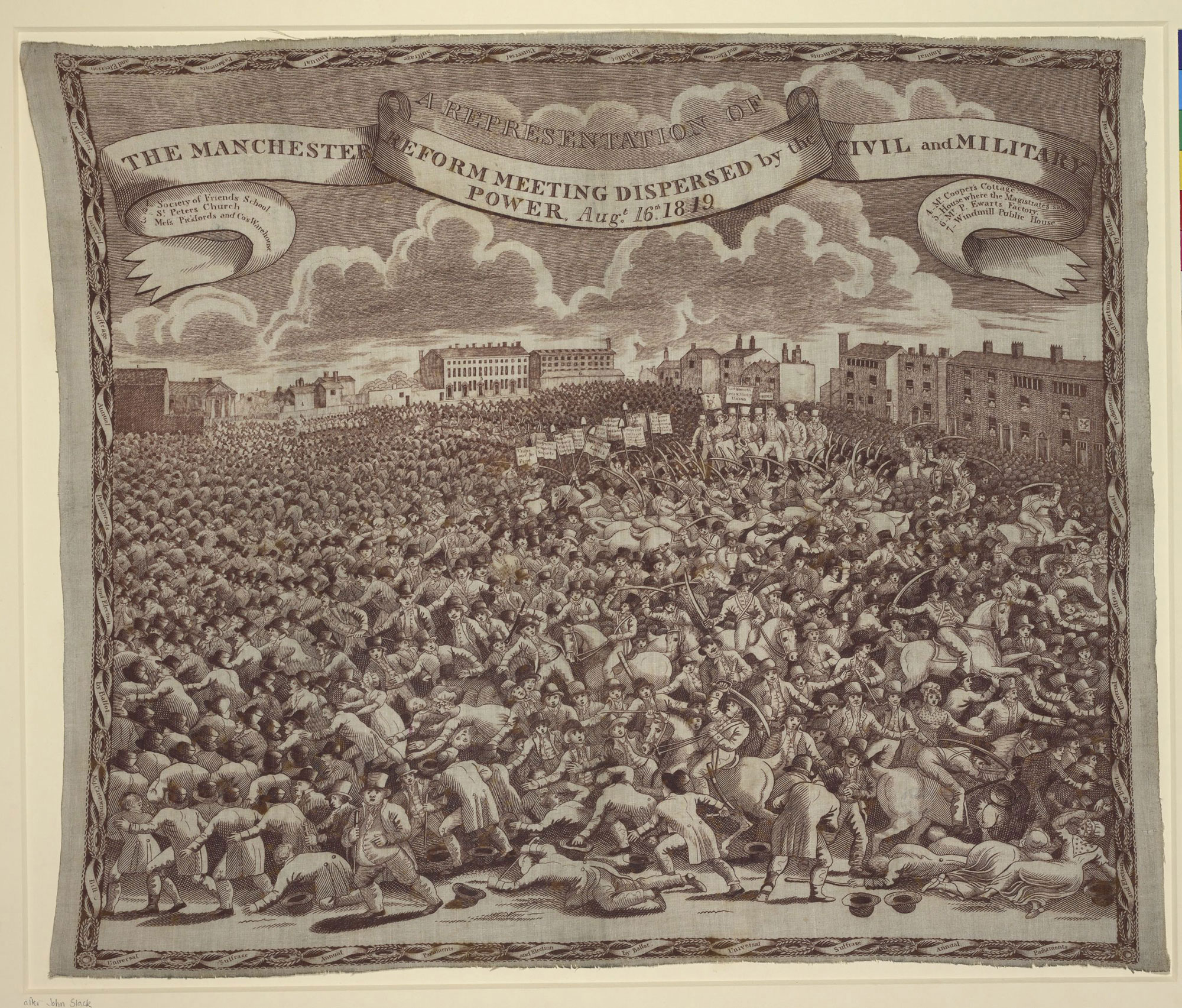

All these social issues worked together to form an increasingly agitated working class who began to meet and explore numerous methods to change the political system which had enabled these pressures. One of these methods was to create an alternative Parliament, though no effort since the middle of the 18th century had succeeded (Thompson, p. 63). Such an attempt was in process in 1819 when a crowd of up to 80,000 met at St. Peter’s Field in Manchester for the fourth of a series of meetings to elect alternative representation who would present demands of parliamentary reform to MPs.

Local magistrates sent the military in to arrest orator Henry Hunt and attempting to disperse the crowd with drawn sabres killed at least 15 and injured hundreds. What has become known as The Peterloo Massacre increased demands for political reform and remained in popular consciousness for decades to come as a defining moment of British agitation. The events were also recorded on numerous souvenirs, household goods such as plates, jugs and handkerchiefs were sold to raise money for the injured as well as communicate the calls for universal suffrage, annual parliament and fairer elections.

Peterloo Massacre Handkerchief (Slack, J., 1819)

Peterloo Massacre Handkerchief (Slack, J., 1819)

These calls led to the 1832 Great Reform Act, proposed by the liberal Whig party after many years of unsuccessful attempts for correcting measures to the electoral system, and allowed cities which had hugely developed during the emerging industrial revolution to have seats more proportionate to their population.

The act made large strides in opening democracy, with the electorate increasing by 49% in size to 656,000 and average turnout increased by a similar percentage (Roberts, 2009, p. 18). However, it did not progress democracy as much as many radicals wished for, and it is on the back of this that agitations and movements developed, resulting in the rise of Chartism.

THE CHARTER

Chartism emerged from an early 19th century movement of radicals developing since the late 1700s with various grievances beginning unify under a shared concern of corruption due to a concentration of political power in a small group of people. Roberts calls this period “the heroic age of popular protest” (2009, p. 27), describing a “combustible combination of hunger, hatred and political diagnosis” leading to mass mobilisation.

There was no single ‘leader’ of Chartism so much as a changing group of radicals with varied political inspiration and an equally varied mix of desired outcomes. This paper cannot do justice to the wide number of voices who fed into the movement, including women, people of colour and disabled, but Thompson (1984, p. 120, and 2015, loc. 1037) explores female Chartists while Chase (2007) intersperses his book Chartism, a New History with studies of several individuals, including the late Chartist leader William Cuffey (p. 303) disabled and of West Indian slave descent who connected slavery struggles with colonialism.

However, one name which appears more than any other is that of Feargus O’Connor, and it was from his lecture tours of 1835 and 1838, with increasingly large audiences, that Chartism established a collective voice and critical mass. His name will crop up several times through this paper, though Chartism can be considered more as a coming together of desperate, angry and active radical voices at a decisive moment of British politics.

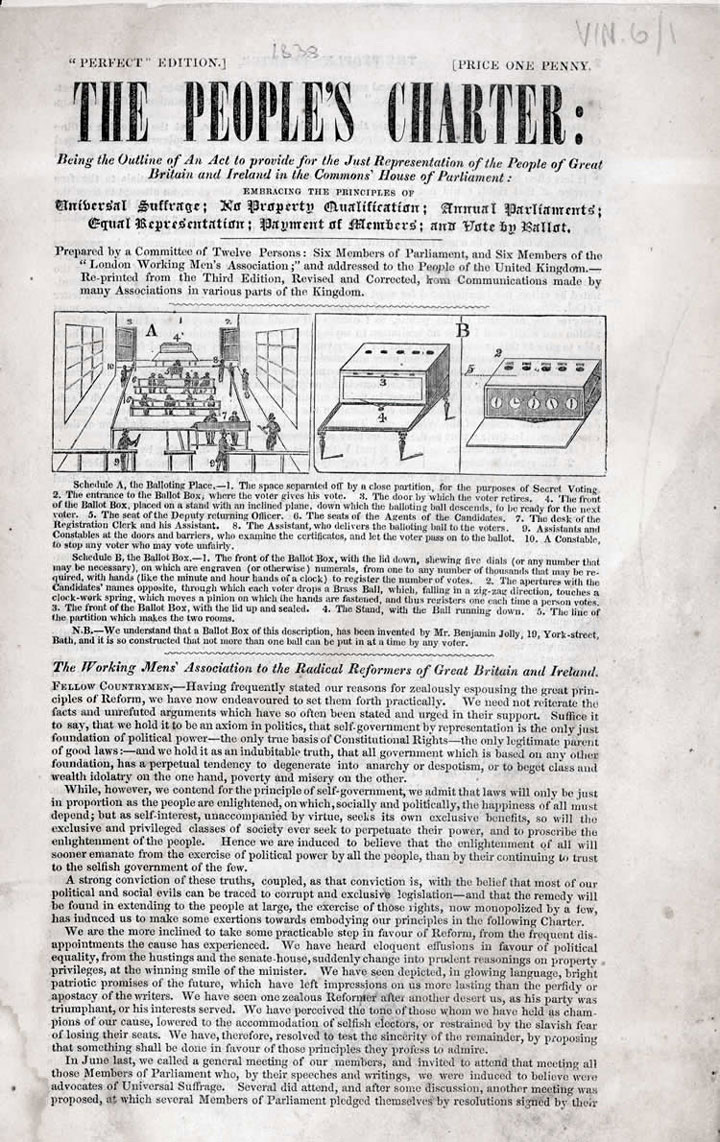

One thing that unified these different radicals was agreement that the root of all social problems was the political system and that the only way to resolve these was through reformation and widening of the suffrage. In 1837 William Lovett and members of the London Working Men’s Association formed a People’s Charter of six reforms they demanded to democratise the political franchise. This became the founding document of Chartism and called for:

-

Universal suffrage — a extension of the vote to all male adults over the age of 21 who were not either insane or had committed a crime.

-

No property qualification — at the time MPs were required to own property of a certain value, effectively blocking most people from standing.

-

Annual parliaments — to regularly hold the government to account and make it easier to replace an unpopular government.

-

Equal representation — most rotten boroughs had been abolished with the 1932 Reform Act there was still an rural/urban imbalance and great differences between constituencies. The Chartists sought to reconcile this creating electoral districts of equal numbers of inhabitants and a single representative for each.

- Payment of members — MPs held their positions unpaid, and as such it precluded most people from standing as their income served to sustain them and their families. A proposed annual salary of £500 was intended to allow not only the exceptionally wealthy to hold political power.

- Vote by secret ballot — public voting using a show of hands was the standard procedure for elections, so employers, landlords and other community members could see how each was voting with the possibility of intimidation and influencing.

The People’s Charter (London Working Men’s Association, 1838)

These points were all calls the public had been increasingly demanding over preceding decades, the Charter simply brought all six together in a more accessible, widely understood and hugely disseminated way, striking a chord with the emerging working class to become what Dorothy Thompson (1984, p. 5) called “the world’s first labour movement”.

Roberts (2009, p. 37) points out that by the 1830s most radicals were seeking ways to activate change by working with or within the existing political system, “using constitutional means to attain constitutional ends”. Equally, the intent of Chartism was to take power politically through widening enfranchisement and representing the working class as a political party. Through the brief years of its existence, Chartism also encompassed other issues though these core six points were held in high regard as natural rights. The movement did not deliver an organised or tight manifesto or set of constitutional plans beyond the six points, but there was belief that through these few aims a social regeneration could resolve the issues of the day.

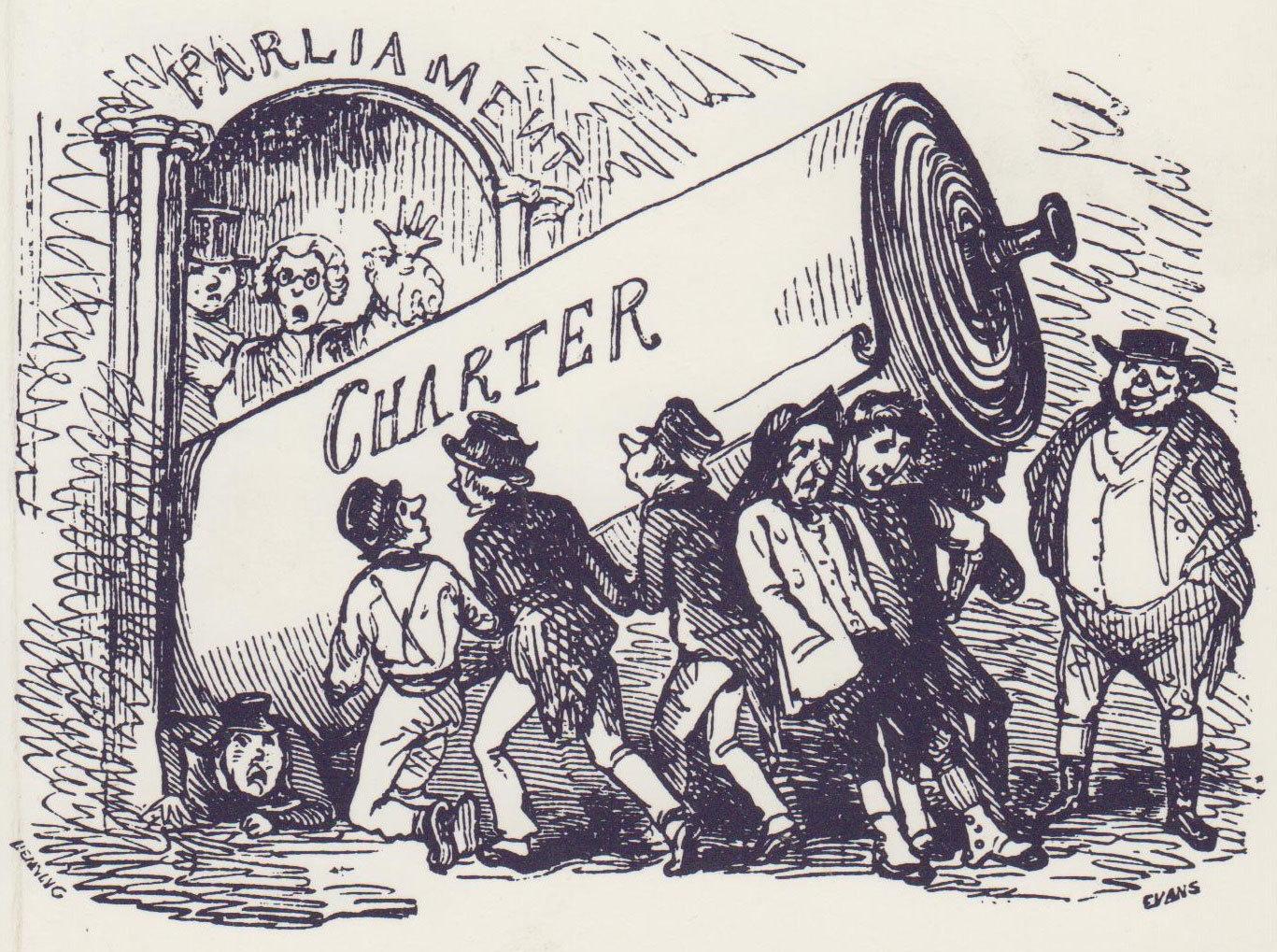

With an ongoing unprecedented economic depression Chartists managed to reach out across the country to gather funds and signatures “without any overarching organisational structure” (Chase, 2007, p. 49). The Charter was widely disseminated nationally with around 640 communities experiencing some form of Chartist activity (Chase, 2007, p. 41) before being presented to Parliament on Friday 14th June 1839. Thomas Attwood, an MP for Birmingham and architect of the Birmingham Political Union pressure group, formed to fight for cities to have parliamentary representation, introduced the petition. He presented his speech to “gentlemen enjoying the wealth handed down to them by hereditary descent, whose wants were provided by the estates to which they succeeded from their forefathers, who could have no idea of the privations suffered by the working men of this country” (Attwood, 1839).

Though interrupted more than once by agitated MPs stating it was a rule that petitions could not be accompanied by a speech, he pushed on to talk of those who had signed the petition with “only three days’ wages in the week” and many who “were paying 400 per cent increase on debts and taxes”. When finishing his introduction Hansard notes that the huge scroll, which had received 1,280,000 signatures, was rolled across the floor of the Commons only for MPs to erupt in “loud laughter” (Attwood, T., 1839). Half-heartedly debated by a half-empty chamber on 12 July, the petition itself was largely ignored while Whig and Tory MPs argued about matters related to currency and the Poor Law before a vote was taken to defeat the Charter by 235 votes to 46 (Chase, 2007, p. 84).

THE HOPES AND METHODS OF CHARTISM

It has been argued that Chartism was never intended as a mass movement so much as a political pressure group with ambitions to both push an agenda to the ruling classes and to widely inform those without franchise the need for a reformed democracy (Royle, 1986). It is in part this lack of deliberate political aim beyond the Charter that Chartists did not have an overarching organisational structure and had no concerted constitutional outlook. This was evident no more than in regards to tax even though both the weight of indirect taxation and increasing costs of living had hit the poor the hardest and that the working class’s economic situation was a direct reason for the emergence of Chartism. An open letter from a Chartist, John Frost, to Lovett (Frost, 1839) noted the transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich:

“Average wages are… from 6/ to 7/ a week; out of this about four shillings goes in taxes. The… Secretary of State receives about £6,000 a year, besides perquisites… Here are six hundred of these poor men paying half their wages in taxes; deprived of the common necessaries of life to enable his lordship to live in luxury!”

Early hopes were that a widening of the enfranchisement would rapidly lead to a direct income taxation system. During speeches of 1938 Feargus O’Connor often spoke of tax burdens as evidence the Charter was required, stating that taxation must move from consumption to property or be replaced entirely by an income tax (Utz, 2013). A move to direct taxation was also increasingly the view of parliament and “middle-class opinion makers” who had come to doubt the Corn Laws, as described by Stephen Utz (2013) in his paper Chartism and the Income Tax.

One area of taxation which the Chartists did think about, but without a clear solution, was the possibility of taxing machinery. Automation was beginning to result in large-scale unemployment, especially in northern industrial towns, as evidenced by Leeds weavers in 1835:

“Their labour has been taken from them by the power-loom; their bread is taxed, their malt is taxed, their sugar is taxed. But the power-loom is not taxed” (cited in Utz, 2013)

However, while there were discussions between the main Chartist taxation thinkers, none quite grasped the conundrum of how to tax machinery to a comparable level of workers’ consumption taxation. They were aware that this difference in tax burden from workers to machines was, in effect, a subsidisation for companies to lay off workers and replace with automation.

In 1834 Robert Montgomery Martin, a taxation expert with access to parliamentary and taxation records published Taxation in the British Empire which uncategorically suggested that an elevated national debt and accompanied tax burden upon the working man could lead to “revolution and anarchy” unless the rich help alleviate the burden upon the working classes (1833, p. v, xx-xxi).

By 1838 a more radical element of Chartists formed the Democratic Association wing with this revolution in mind. Inspired by French agitator François-Noël Babeuf who in the late 1700s was known as an advocate for democracy, leading calls for a popular revolt against the government. In 1845 Engels (2010, p.6) wrote of the Association:

“While the great mass of the Chartists was still concerned at that time only with the transfer of state power to the working class, and few had the time to reflect on the use of this power, the members of this Association, which played an important role in the agitation of that time, were unanimous in this: — they were first of all republicans… rejected all ties with the bourgeoisie, even with the petty bourgeoisie, and defended the principle that the oppressed have the right to use the same means against their oppressors as the latter use against them.”

Despite increasing wealth being made from factory and land owners, working conditions for labourers were not improving. Workers suffered intrusive discipline, long working hours and minimal breaks (Chase, p. 21) with conditions encouraging heavy drinking (Chase, p.170). Strikes were a constant threat since the initial Charter petition was presented to Parliament, with many Chartists calling for a “sacred month” of strikes should it be rejected by MPs (Chase, p. 79–81). Though low union membership, in part due to the transportation of the Tolpuddle ‘Martyrs’ in 1834 and Glasgow cotton spinners in 1837, and fear of heavy-handed police response (the Peterloo Massacre was still in popular memory) the strikes, as well as the hoped-for revolution, did not come about though the tactic remained an ever-present possibility.

The Democratic Association only lasted until 1839, however looking back Engels added that their “effectiveness was not wasted and it greatly contributed to stimulating the energy of the Chartist movement and to developing its latent communist elements.” (2010, p.7)

In 1842 a second Charter petition — six miles of paper with over three million signatures, around a third of the adult population and three and a half times the electorate for the 1841 general election — was presented to Parliament (Chase, p. 205).

Sketch of the Delivery of the Charter (Unknown artist, 1839)

Again, it was duly rejected, but with nationally low wages alongside high unemployment, this time leading to a general strike across the land. The strikes inspired a sense of the France revolt which led to the 1789 revolution, with a Lancashire landowner describing the atmosphere as a bubbling volcano (Chase, p. 192). In many locations people committed serious violence which was frequently responded to with equal force from the authorities, though by August energy for the strike was sapping in part due to numerous deaths from hunger (Chase, p. 225).

The London of late 1700s has been described as “the riot capital of the world” (German and Rees, 2012, loc. 1939) and ever since the Gordon Riots the authorities had been fearful of mass physical uprising. 1842 was the year that Britain came closest to revolution that it ever has so far, and the authorities realised this threat and arrested, imprisoning and deporting hundreds with a concerted attempt by the authorities to shut Chartism down by arresting all the leading figures.

The movement of the Chartists had been largely based on mass crowds and event based protest. As mentioned, O’Connor’s early leadership was based upon his lecture tours which involved increasingly large audiences. The first years of Victorian times were primarily oral and while literacy was growing outdoor mass meetings, for which people would walk many miles, were the key vehicle for extending political idea (Chase, p. 4, and Thorne, p. 17). These would only grow as Chartism grew and the public became more politically aware, and aware also that politics may offer the only route from hunger, destitution and lack of agency. Mass-gatherings frequently involved crowds of hundreds of thousands who walked miles to protest and hear speeches (Roberts, 2009, p. 27) with an increasing air of physical rage.

Chartist Meeting Poster (Unknown designer, 1848

Chartist Meeting Poster (Unknown designer, 1848What turned out to be the finale event of the Chartist mass-gatherings was in 1848. Posters advertising a demonstration on had been put up around London and groups of activists met at local meeting points before converging upon Kennington Common. Other posters criticised the mass press for seeking to diminish the Chartists’ call instead of appreciating the demands of the hungry, overworked and those in social difficulties (Rosenberg, 2015, p. 33). Due to revolutions erupting across Europe the authorities were on edge and declared the meeting illegal, though it did not stop crowds gathering.

The third of the three mass-petitions which were delivered to Parliament by the Chartists was delivered to Westminster from Kennington Common. The 1839 petition had received 1.3 million signatures, the second of 1842 had over 3 million names. This third petition of 1848 was claimed to have 6 million, though this was disputed and may have had more like 2 million names (Chase, p. 312).

The politicians of the day ran an “effective media campaign belittling the Chartists” (Chase, p. 313) through the mass-press, reporting that the attendance at the rally was 15,000 opposed to the estimated 150–250,000. The Times stated that, in fear of mass violence that would lead to the kind of insurrections that were happening on the continent, 150,000 special constables, many armed, and military were enrolled to police the city (Thorne, 1966, p. 41).

As expected, the Charter was rejected by Parliament and while London didn’t experience the violence or rioting as it had on previous gatherings, the summer of 1848 did witness troubles across the country (Thompson, 1984, p. 328). Wide-ranging social grievances were the background to the rioting, while the rejection of the Charter was a trigger. The movement, however, became tainted by association to the wave of crime and rioting. Coupled with the increased organisation of the police force in the 1840s Chartism began to become ‘controlled’ by the authorities, and Kennington Common, site of many a political meeting aside from the Chartiss, became enclosed as a public park by Royal Ascent by 1854. This relates to a tightening of control by municipal authorities over public space, often simply by building over it, as a method of restricting the public mass platform (Roberts, p. 60) with a secondary effect of forcing radicalism ‘indoors’ and out of the public eye.

But the main fact that the great meeting of 1848 did not rise into revolutionary desire was evidence that, as Marx is quoted as saying in Thorne (1966, p. 44), that the British had “all the material necessary for the social revolution” but lacked “the spirit of generalisation and revolutionary ardour”.

Photograph of Kennington Common Meeting (Kilburn, W., 1848)

Photograph of Kennington Common Meeting (Kilburn, W., 1848)

The petitions, which were the purpose of those three mass Chartist meetings, which were each presented to Parliament aided a sense of collective identity and shared action (Roberts, 2009, p. 29) though were perceived as being a middle-class action by some Chartists who favoured more direct to work against the political system rather than with it. However, there was something powerfully symbolic, which resonates to this day, of a ‘delivery’ of a list of citizens’ names, especially when in the 19th century these were such physical objects carried on shoulders and ceremoniously presented.

The other form of mass-information which was critical to the movement was independent press and pamphleteering. What aided Chartism’s rise more than any previous social movement was the ease and ability they had to spread ideas and plans of action around the country at speed and counter to the mass-press. Thompson (1986, p. 37) describes the story as well as any other writer on the topic, including the constant battle against stamp tax levied by the government to control distributed news.

Between 1810 and 1832 newspaper sales went from 16 to 30 million (German and Rees, 2012, loc. 1990), and from the 1830s the media landscape grew to include a politically diverse range of newspapers. From this period the taxation on paper and stamp duties were gradually rescinded until all duties were gone by 1855. It was in this period that Feargus O’Connor established a weekly Chartist newspaper, The Northern Star, which was used to promote Chartist issues and ran campaigns in support of the working class who were financially suffering through falling wages and automation in factories. The first issue coming in late 1837, after one year it had a circulation of 10,000 which had reached 50,000 a year later. From 1843 Engels regularly contributed to the Northern Star and from 1847 extended the international approach to political change by writing about updates on the Chartist movement for the French newspaper La Réforme, particularly on the Irish movement for national liberation.

Front Page of the Northern Star (The Northern Star, 1839)

Front Page of the Northern Star (The Northern Star, 1839)

In 1847 Feargus O’Connor was elected MP for Nottingham, replacing Whig John Hobhouse, to become the first and only Chartist MP. Engels and Marx optimistically proclaimed this act as a sign that “the new period of Chartist agitation has entered with the final defeat of the third party, the aristocracy” (2010, p.59). In the same year O’Connor launched the Chartist Land Plan and set up a company, the National Land Company and a separate Land and Labour Bank manage project finances. In short, participants could buy shares in the scheme at a low cost which entitled them to enter a ballot for differing amounts of land from six sites around the country which had been purchased with the central fund. The scheme plugged into a romantic connection to the land which goes back in English radicalism and culture (see Howkins, 2002) as well as offering hope of an escape from the dirty industrial towns and a new self-sufficient start in a like-minded community without the precarity of a landlord and rising costs of living (Tiller, 1985).

There had been several other schemes to ‘return’ people to their ‘stolen’ land over the preceding two decades, but it was the Land Plan which grabbed the most popular interest, not least because O’Connor used his newspaper to publicise the scheme. However, the project wasn’t supported by all Chartists, notably Bronterre O’Brien opposed it and argued that all private ownership of land was wrong, calling instead for nationalisation of land with purchases gradually taking place using rental return from already owned plots (Tiller, 1985).

1889 Map of Chartist Village, Great Dodford (Unknown cartographer, 1889)

1889 Map of Chartist Village, Great Dodford (Unknown cartographer, 1889)

The cottages for the Land Plan sites were designed by Suffolk Chartist John Sillett and he was invited to recreate them for the Great Exhibition of 1851 (Chase, 2003). 250 settlers moved into new communities (Thorne, 1966, p. 29) and the project received praise from John Stuart Mill (Howkins, 2002, and Chase, 2003) though by 1951 the scheme had collapsed, wound up with debts and Mill quietly removed reference to it by his third imprint (Chasse, 2003). Despite financial failure and disorganised leadership, the project is largely looked back on fondly as an important experiment in independent agency, if flawed.

The Land Plan was the last great act of Chartism. As Thompson (1984, p. 306) explains, “the Chartists had tried petitioning, they had tried the weapons of strike, the mass demonstration, even an attempted rising” before they moved to the “self-help” approach of the Land Plan. There have been many explanations exploring the decline of Chartism (including Rowe, 1968; Thompson 1984, p.330; Royle, 1986; Chase, 2007, p. 326 and Roberts, 2009, p. 44) though the decline of the movement isn’t so much the purpose of this paper’s exploration so much as the social conditions which enabled it.

The Great Exhibition itself may have been partly responsible for the post 1848 lull in radicalism and unrest, alongside a comparative improvement in the economy. However, if it did it was only a partial respite for the rest of the 19th century soon returned to political agitation, much inspired by the roots founded by Chartism.

Chartist cottage (Mistletoe, 1889)

Chartist cottage (Mistletoe, 1889)

A COMPARISON WITH THE 21ST CENTURY

All the discussed political and social issues in the years preceding and during the Chartist period are already probably reminding the reader of current neo-liberal issues affecting early 21st century society. The half of the paper will consider the parallel situations arising in Britain over the previous decades of neo-liberal politics as an exercise to consider events of the 19th century which rhyme with our current situation.

“I don’t think it’s inevitable at all. I just think that we need massive revolutionary change in the way that we do things, and it’s not enough to say that we can’t even talk about the necessity of that because it might have [ugly consequences].” (Aitkenhead, 2017)

So says Steve Hilton, former strategy advisor and right hand man to David Cameron, in a Guardian interview which began in his $20m and continued over an hour long Uber journey to his son’s private school. He goes on to say, “I’m rich, but I understand the frustration people have” before claiming that he isn’t in the “super-rich” category. In 2016 Hilton moved to California where his wife, Rachel Whetstone, had recently left her job as Director of Communications at Google for a similar role in Uber. As a power-couple, Hilton and Whetstone symbolise the tight relationship between big business and the political elite, though where the business of the Chartist years were factory owners in the 21st century it is the technological industry which is now pushing for political power.

In April 2017 Whetstone abruptly left her job at Uber (Hern, 2017) amid allegations of corruption and a “chumocracy” between the top of British politics and Whetstone’s technological employers. The Daily Mail, hardly the bastion of holding the political right to account, reports that the “picture is of a closed, corrupt, incestuous elite, a cabal of back-scratchers and nest-featherers” (Sandbrook, 2017). The ongoing allegations relate to assistance from the top of British politics to drop Uber regulation plans, that Google had a “revolving door access to №10” and that both firms were involved in tax avoidance.

Uber’s business model is based upon the workers, in this case private taxi drivers, not being registered as employers for the company but operating on a zero-hours contract. This is commonly called the “gig-economy” and now counts for a whole class of workers who are paid per “gig”, presented to the public as offering flexibility and self-determination, the model in turn lacks most of the working protections built up over many decades. The 2016 McKinsey Report found that five million people in the UK work in the gig economy (Marston, 2016) while the service industry, in which the it primarily operates, accounts for nearly 80% of GDP (Martin, 2017). This all sounds like the 19th century factory owners who increased personal profit by employing workers on daily contracts, and minimising their obligations for welfare or workers’ rights.

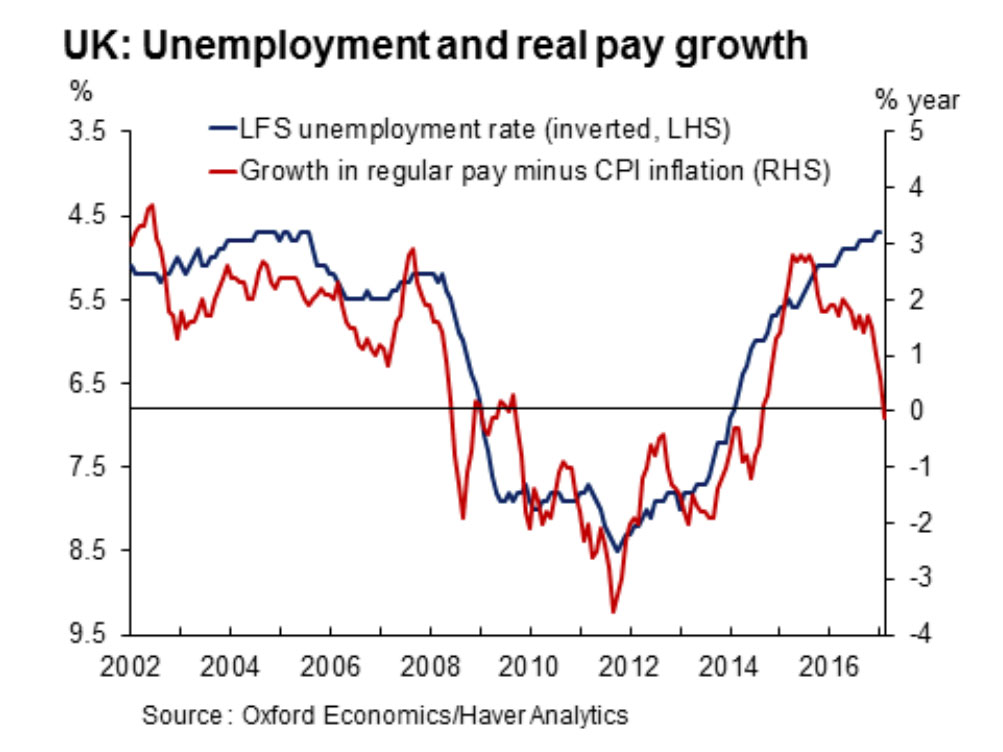

Uber and other tech firms who rely on this employment mechanism have forcefully opposed unionisation and workers’ rights such as minimum wage, sick-leave or paid holiday on the basis that they are “self-employed contractors” and not employees, adding the threat that introducing workers’ rights could lead to companies go out of business (Raychaudhuri, 2016). While unemployment appears to go down, because more people register as self-employed to suit the new economy even if they have little or no earnings, the average worker is getting poorer as growth of earnings is lower than inflation (Martin, 2016).

Graph of Unemployment and Wage Growth (Oxford Economics, 2015)

Graph of Unemployment and Wage Growth (Oxford Economics, 2015)

Just as the Chartist movement was a struggle for the working class against the emergent industrial revolution, so any 21st century movement would be a struggle against the economic changes of the emerging technological revolution — one Chinese mobile phone factory increased productivity by 250% by simply replacing 90% of its human workforce with machines (Sheffield, 2017). The new technologies of the 1800s, such as the weaving equipment discussed earlier, largely affected the working classes more than the ‘traditional professions’ but 21st century technological changes will cross traditional class and professional boundaries (Walport, 2017). An economic future based on algorithms, new contractual relationships and smart technology has the potential to upset ethical, financial and social structures more than in the 1800s.

In Britain this could see one in three jobs replaced by automation by 2030 and could expand the divide between London and the North (Elliot, 2017). The unemployment of the 1980s and 1990s through de-industrialisation and movement to the financial and service industries may offer a warning for the potential social changes ahead resulting from automation.

Just as Chartists and other early 19th century radicals proposed new economic mechanisms for dealing with automation, new ideas are emerging now too. A robot tax is being discussed in just the same way as the Chartists discussed taxing machinery (Bloemenkamp, 2017). Other economists are suggesting radical overhauls of welfare and taxation to reflect the new situations brought about by a changing economy and new political circumstances. Professor Guy Standing is a leading advocate of Universal Basic Income as a system to distribute collective wealth more evenly, which is in effect an updated version of Thomas Paine’s late 18th century ideas on asset-based egalitarianism (1795) which Chartism never explored.

The Chartist responses, as outlined earlier, were related more to income tax and property tax structures (Utz, 2013). A reorganisation of property tax is still a proposal presented by many to redistribute wealth with increasing support, across the political spectrum, for a Land Value Tax. Similar to Universal Basic Income, a land tax had been discussed pre-Chartism — Adam Smith arguing in the Wealth of Nations of 1776 that a “tax on ground rent would prevent landowners from gaining monopolies” Minton, 2017) — but was not picked up as a possible mechanism by the movement.

Monbiot (2016, p. 283) states that “it is altogether remarkable, in these straitened and inequitable times, that land value tax is not at the heart of our current political debate” while the New Economics Foundation states that while fundamental changes in the way land is taxed may seem radical “the alternative is worsening inequality, rising prices and rents and, eventually, economic and financial collapse as the bubble bursts yet again” (Collins, 2016).

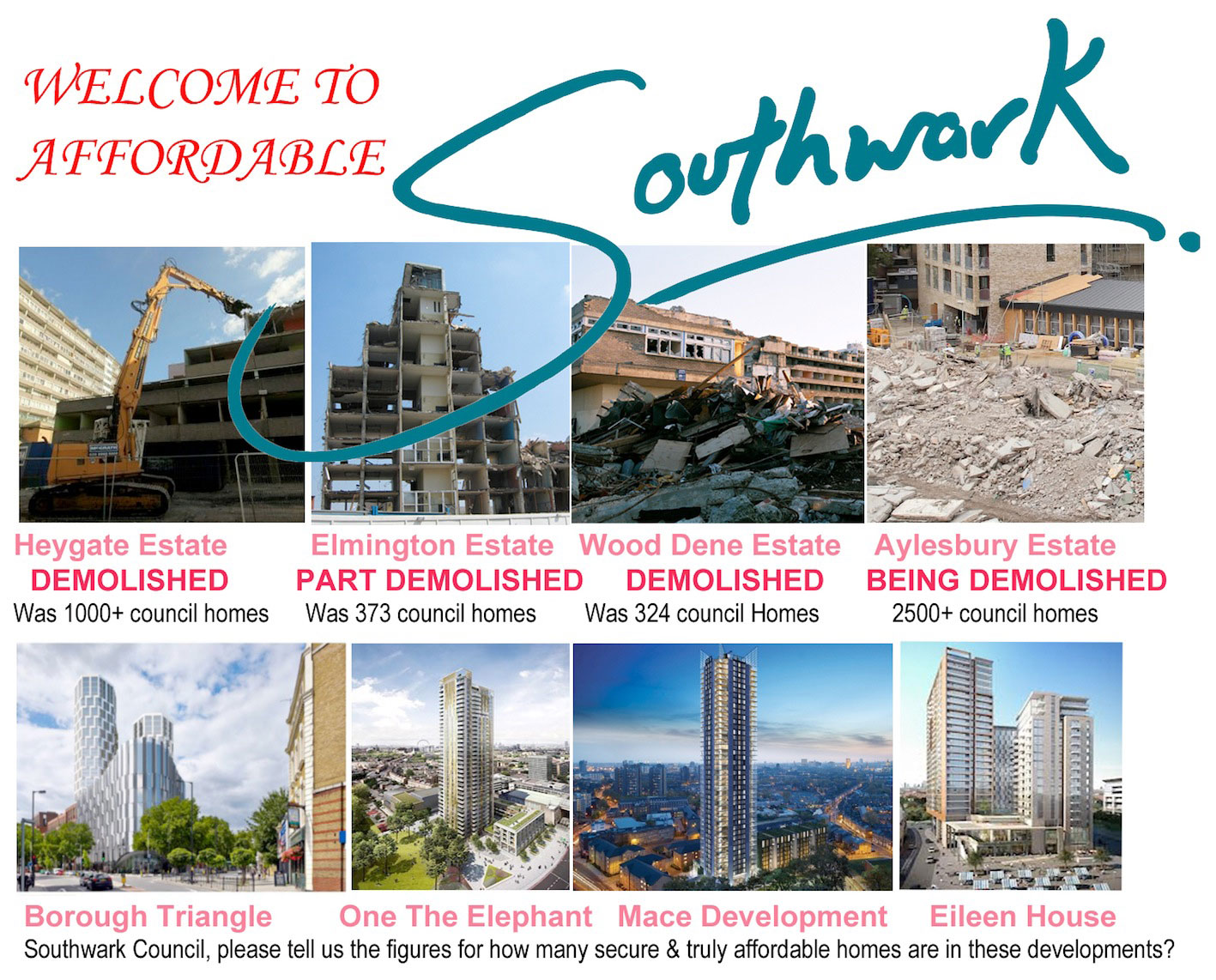

I would make comparison between the ongoing housing crisis with the consequences of the enclosure act. To a predominantly rural population, having access to land for sustenance and shelter was key to a secure existence, while in our urbanised society, where neo-liberal policies are taking strongest effect, the housing crisis is the largest risk to individuals’ security.

Enclosures, as discussed, removed from people their sense of personal agency within the larger economic system and put their rents at the hands of landlordism which had the primary interest of profit from the tenants. Roberts (2009, p. 36) states that “parcelling out land for cultivation supplied workers with the means to liberate themselves from the tyranny of capitalism”. Models of housing, such as Community Land Trusts, can be seen to be a distant relative of the Chartist’s Land Plan and are mechanisms by which citizens can take themselves out of the tyranny of the housing market and remove land from the free-market.

There is a huge unaffordability for renting or buying, with average UK property prices an average of nine times average income and up to 20 times in more desirable areas (Collins, 2016). Minton (2017) discusses an increase in property prices with no increase in average wages leaves “a third of households… locked out of the housing market” creating a cost of living situation affecting the working class more than any other not dissimilar to the early 1800s.

Discussing the enclosure acts between 1760 and 1840, when one sixth of England was changed from common land to enclosed, Fairlie (2009) discusses the debate of Enclosure bills for Oxfordshire where there was no requirement to declare conflicts of interest:

“Out of 796 instances of MPs turning up… 514 were Oxfordshire MPs, most of whom would have been landowners. To make a modern analogy, it was as if Berkeley Homes, had put in an application to build housing all over your local country park, and when you went along to the planning meeting to object, the committee consisted entirely of directors of Berkeley, Barretts and Bovis — and there was no right of appeal.” (Fairlie, 2009)

As comparison, Minton (2017) discusses the House and Planning Act 2016 which has huge implications for affordability of housing, access to the market and planning permissions for land in the UK. Councils will be able to bypass normal democratic process for urban brownfield sites which can have automatic ‘planning permission in principle’, described as “a wholesale power grab” (Wainwright, 2016) as well as replacing secure lifetime council tenancies with precarious two to five year tenancies. Minton (2017) describes how the Act also “opens the door to the direct privatising of local authority planning by allowing developers to choose private sector consultancies, rather than local authorities, to process planning applications”. The Commons ‘debate’ on this “highly contentious” bill was held overnight with reports of the Conservative MPs who had turned up to listen laughing and playing games on their phone (Topple, 2016).

Estate Regeneration in Southwark (Southwarknotes, 2015)

Estate Regeneration in Southwark (Southwarknotes, 2015)

The current situation of ‘estate regeneration’, the stock transfer and mass demolition of entire housing estates followed by new developments is state-supported social engineering whereby private developers, private landlords and politicians work together in a method also not dissimilar to that of the enclosure acts just described. Add into the mix that 20% of MPs are landlords, compared to a national level of 3%, and that there are concerns of a “revolving door between council employees and elected members and developers” (Watt and Minton, 2016), which suggests the situation of 2017 is arguably not too dissimilar to the early 19th century at all.

The Chartist Land Plan, as discussed, was popular not only because it offered a strategy for individual agency and a step away from the precarity of landlordism, but also because the quality of life in the city during the emergent Industrial Revolution was becoming insufferable. We saw earlier evidence of the appalling and unsanitary conditions that people were forced to live in in the early 19th century and it is increasingly a similar situation in 2017 with “even wealthy young professionals being forced to rent in squalid conditions” (Ellson, 2017).

Outside of the home there are also conditions in environmental quality with parts of London reaching annual limits of nitrogen oxide within five days of 2017 (Carrington, 2017). The smog pollution of the 19th century may have been visible, but pollution we are living with in 2017 has now been stated by Theresa May as the fourth biggest public health risk alongside cancer, obesity and heart disease (Peck, 2017). It is good that the Prime Minister raises attention to such risks, but it’s potentially meaningless now the post-Brexit Great Repeal Bill has put 40 years’ worth of environmental regulations and orders at risk (BBC, 2017).

Pollution in London (Green Party, 2014)

Pollution in London (Green Party, 2014)

There are countless other examples of social ills which have multiplied over the last two decades of neo-liberal policy which are reminiscent of the early 19th century social conditions, and all have amplified over the previous few years of ‘austerity’ measures under the Conservatives. The £12b of benefit cuts which the current government are undertaking suggests the “being cruel to be kind” mentality of the New Poor Law is still policy 200 years on (Ryan, 2015). Cuts to child welfare, which affect the poorest of society, are occurring at the same time as the wealthiest benefit from over £2b a year in tax cuts (Butler and Asthana, 2017).

The current socio-political divides, often fuelled by the mass-press, between the North and the South, Scotland and England, London and outside of London, between classes, professions and ethnic backgrounds needs to be confronted and overcome. Rowe (1968) discusses a main failure of Chartism was the lack of connection between London and the north, that activists in the capital preferred a soft, participatory approach while the north, where social pains were felt harder, where driven towards physical revolt. In London it was “the educated artisans and not the poor labourers” who were interested in Chartism (Rowe, 1968) and while wages in the capital were not high for the lower classes they were more stable than the north. Complaints at the time suggested London Chartist meetings were polite and mannered rather than riled and angry as they were elsewhere, and there was perhaps a sense of apathy in London politics which wasn’t present elsewhere.

While there are clear divides between London and the north now, there is also a clear apathy across the whole of the voting population reflected in election turnout dropping hugely since 1997 (UK Political Info, 2015). Just as Chartists called for wider enfranchisement and a rebalancing of the political landscape to give fairer voting to the expanding urban centres, so there are calls now for a change to a proportional representation system, opening the political landscape to offer more plurality.

The Chartists were fighting against the two party system of Whigs and Tories, neither of whom were considered to have the working class’s interest in mind. Once the liberal Whigs sided with politics which aided the emerging middle classes, primarily with the Corn Laws, it opened a chasm, leaving the lower classes without a voice and everything to fight for. Later during the Chartist period social conditions had begun to hugely affect the middle classes too, and so the emerging working class agitation bean to find support from those above, resulting in the vast petitions and mass cross-class movements which scared the political establishment.

The existing centrist political landscape, whereby different political voices including those from the left and right are forced into the status of fringe despite picking up enough votes to offer a more balanced system (BBC, 2015) creates a similar landscape whereby the breadth of political discourse is limited, solutions are constrained and apathy spreads through a population who feel disenfranchised.

Since election turnout plummeted after 1997 politics has largely been rooted in a participatory approach, especially in relation to public services (Bordeau and Wilkin, 2015). The recent attempts at a Conservative ‘Big Society’ can be traced back to the 1840s when the New Poor Law reduced political responsibility for those in need forcing the development of later Victorian philanthropy and self-help. Philanthropy led social improvements frequently had a commercial benefit to the those with the money, with the example of new public parks offering green space but also bringing inflated land values and opportunities for speculative development.

However, participatory politics is a façade of engagement, offering “free schools” so long as they are approved by the political establishment and are on-message, offering a choice of how your council estate is demolished rather than if it is, your choice of privatised health provider, and so on. Just as Uber or AirBnB capitalise on the suggestion of mobility and free-choice to present the image of participatory employent, current democracy uses the vocabulary of participation to “construct the meaning of the public and direct it to elite-approved ends” (Bordeau and Wilkin, 2015).

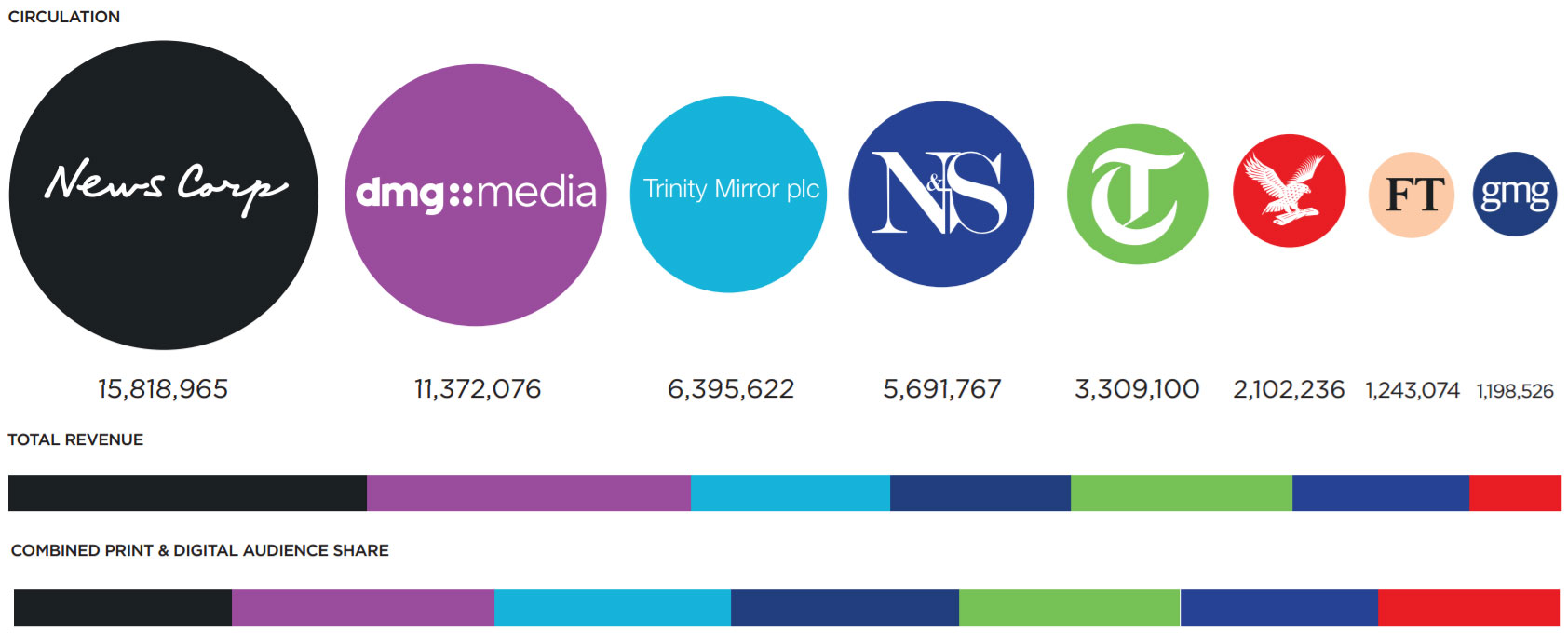

Part of the problem lays with a mainstream media which sees six companies account for 80% of local newspaper titles, only 14% of radio being independently owned, 90% of web searches running through Google and over 50% of national newspapers being owned by two billionaires (Media Reform Coalition, 2015). 19th century radicals sought to reduce newspaper stamp tax before the newspaper landscape widened vastly, offering a plurality of voices to be heard. Radicals of the 21st century have unrivalled access to self-publishing and dissemination through the internet, but as discussed when the new gatekeepers have a revolving door to the top of politics we may be facing similar battles over the next decades.

In addition, mainstream media imposes a binary win/lose system when it comes to reporting on public or political battles, Douglas McLeod argues this doesn’t help protest groups or those seeking new voices because they “have many other kinds of more tacit or latent goals… like building solidarity, providing avenues for expression, networking, getting like-minded people together and also… learning amongst the movement members and helping give the public some insights into their particular perspective” (Long Road to Change, 2017).

UK Newspaper Circulation and Revenue (Media Reform, 2015)

The question of agency stretches into the physical realm as well as political, both now and 200 years ago. The Enclosure acts, as discussed, removed public rights from those who used the land for livelihood and self-sufficiency. The current battles for loss of public space and the change of public spaces to privately owned or managed does not affect the public in the same way, but it does affect our sense agency and autonomy in the physical and political landscape.

“So the question is why does this matter? It’s not any longer a matter of livelihoods, of grazing sheep, gathering firewood, but I would suggest it’s about a certain kind of freedom, a certain ability to make your own space in a city that isn’t kind of scripted and programmed for you by whoever might own it.” (Rowan Moore speaking in Donald, A., Moore, R., Self, J. and Williams, A., 2016).

Take the proposed Garden Bridge, a partially publicly funded but privately owned tourist attraction in the centre of London which is as much a result of the chumocracy as Uber was previously discussed (Jack, 2016). Imagined by actor Joanna Lumley and designer Thomas Heatherwick it turned from a concept in their heads to an actual project potentially costing over £200m solely due to Lumley knowing the then Tory Mayor, Boris Johnson, since he was four years old.

Architecture writer Jack Self argues that the project is “representative of a state of civil war in London” (Self speaking in Donald, A., Moore, R., Self, J. and Williams, A., 2016), adding that it appears to be “wholly undemocratic” and he doesn’t know if he wants “to live in a society in which two eccentrics [can do this], I don’t know to what extent a private interest has the right to construct public space.” His argument that it represents civil war is based on it being “indicative of a paradigmatic failure of politics in western society at large and in Britain in particular” where the “interests of the private overcome the idea of politics” and “the interests of the people are subsumed below the interests of a private corporation”.

In his argument for Universal Basic Income Guy Standing talks of 2017 being an important year for the public, when “insecurities and inequalities reached such a point that there can only be a revolt” (Standing, 2016). He suggests that the proposed Garden Bridge and the privatisation for profit of the national river, may lead to “huge marches, huge protests” to reclaim the commons which have been privatised and sold off, “the social commons, the spatial commons, the cultural commons” (Standing, 2016).

The privatisation of spaces also helps control the kinds of mass-gatherings which the Chartists used to full effect and which terrified the ruling classes. The enclosures of commons into parks, including that at Kennington where the 1848 mass meeting took place, largely happened to enforce this control over the public and their spaces. Any new radical uprising will need to reassert ownership of the physical realm as well as fight to retain public open, unmonitored access to the digital realm.

Michael White suggests mass-marches, such as the Womens’ March, are self-congratulatory and do little to aid change. He argues that such marches, which are state-sanctioned and managed, “lower the horizon of possibility” (Long Road to Change, 2017) and that we have “a crisis of sovereignty where there’s no real direct way for the people in the streets to… manifest a higher form of sovereignty over their government that forces their governments to do what they want” and that new strategies are required.

This is backed up by Clare Foges, former speechwriter for David Cameron and coincidentally a Trustee of the Garden Bridge, who says she is “embarrassed” by protest which just burdens the state with policing costs:

“I worked for five years in No 10. No matter how big the protest outside, it never once felt like the enemy was at the gates… I remember being in a hotel room 20 storeys up, working with the prime minister, then looking down at the protest below: fluorescent yellow police ants, lots of protesters, their chants unheard in our sealed-up air conditioned hush. And thinking: poor things! What a waste of time. No one’s listening. The protest is so banal it has become backdrop. The collective noun for protesters should be a smudge, or perhaps a wallpaper.” (Foges, 2015)

This rings true to anybody who attended the marches against going to war with Iraq in 2003 which made no effect upon the political narrative. Indeed, the mass public actions which have had more impact than any other in recent years are the poll tax riots and the student protests of 2010, while the London riots of 2011 made more political impact than any polite protest march. Perhaps 2011 was a simmering release of pressure from the volcano, a volcano which may yet blow considering the “underlying conditions… still persist” (Tim Newborn in Fishwick, Z. and Fishwick, C. 2016). Perhaps future mass-actions need to instil the fear which gave the Chartist movement strength.

The Poll Tax Riots of 1990 (Unknown photographer, 1990)

What petitions such as those on Change.org do offer, however, is an easy way to develop a digital mailing list of like-minded citizens which can be a critical part of any political organising or dissemination of information, just as the Chartists found that mass-meetings offered a unifying point where people could come together to turn individual grievances into shared political issues. Though the actual petition itself may have as little effect now as they did 200 years ago when Tory MPs simply laughed at them being delivered into the Commons. Even though this ineffectiveness did not stop over 4million citizens vote online for the government to trigger a 2nd EU Referendum (UK Government and Parliament Petitions, 2016) there is a risk that it is simply part of the participatory approach of politics to give people the façade of action while simply persevering with the neo-liberal path.

“I think there is a bit of a problem now. I think people see themselves as activists if they’re clicking to sign a petition or they’re retweeting something. You know that’s not going to cut it these days. I think people have kind of got a bit lazy, you’ve got to get involved in campaigns, you’ve got to do the hard work and I think people have got a bit of a false sense of how change happens.” (Rosie Rodgers of UK Uncut in Long Road to Change, 2017).

Whichever methods are used and whichever voices are heard, there are numerous parallels in the first decades of the 21st century as those of the 19th century. Now, as then, the repressed voices are those which will look to fight back, and their number will grow as the effects of neo-liberal politics effect ever-increasing numbers of the middle classes.

Guy Standing talks of the precariat, a class of people extending beyond the traditional working class strata and including everyone who experiences unstable labour, reduced working rights, working below their educated level, who has no pensions, benefits, holidays or medical leave. All the things, Standing argues, “that the 20th century had accepted as the growing norm” and which he claims will surpass 50% of the population during 2017.

“Anxiety, chronic anxiety, where’s my next bread coming from, how am I going to pay those debts, how am I going to do it? And anger. And then we [move] into the next phase of the fightback. The fight for representation. Our voice, our agency, our sense of empathy and solidarity must be in the centre of the political stage. That phase [begins] slowly with new political movements, fighting against the old structures and old Social Democratic, Christian Democratic, neo-liberal policies and saying, “They are dead men walking. We are not.” (Standing, 2016)

CONCLUSION

There has been an increasing amount of popular unrest increasingly through the last three decades of neo-liberalism. The years of New-Labour and their introduction of a participatory democracy may have diffused the anger which had been rising during the Conservative period preceding it, but it may only have acted as a short-term reprieve in the same way as the 1832 Reform Act. There is wide opinion now that the project under Blair and Brown simply continued the same processes which had emerged under Thatcher, and through it had used the state to allow public money to improve the profit of corporate entities and decrease the political agency of the man on the street.

The Lib-Con government began a process which not so much stripped back the state, but increasingly moved the welfare state and civil responsibilities into private hands subsidised through public taxes (Bordeau and Wilkin, 2015). Just as the government of the 1800s put the debt from the Napoleonic wars onto the shoulders of the working class, so do the governments of the 2000s shift the costs of the financial crisis, also a debt not of their making, onto the shoulders of the working population (Bordeau and Wilkin, 2015).

However, the organisation and political agitation across many sectors, and classes, of society is rapidly growing. Chartism had effect because it emerged to transgress beyond the put-upon working class voice, which was easily silenced or reduced, and began to encompass the voices of the middle classes who also saw their lives effected through the economic decisions of the ruling classes.

Whether it is Black Lives Matter, community groups fighting developments, action against closing of libraries, wide reaching marches against Brexit or Trump or more, there is a growing collective feeling of need to reform the neo-liberal system. But what is lacking in our politics, thus far, is a unifying statement or wider call to action which underlines the critical issues which are increasingly shared by so many of society and which underpin all of the individual action movements. In 1838 this took the form of the six point Charter which emerged around mutual concerns from various sectors and classes, can there be an emergent version for the 21st century?

We are currently entering a period of uncertainty which contains many of the same ingredients which led to the near-revolution of the 1842. In a late neo-liberal, post-Brexit world where not only Trump can become President but right wing politicians are given legitimacy across Britain and Europe to a level not seen since the 1930s, the bigger question needs to be not how we stop the uprisings but how can a collective narrative be embedded into the growing unrest so that when radical changes are inevitably made they are done so with societal improvement at their heart rather than a continuation of inequality and the top benefiting from the bottom of society.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aitkenhead, D. (2017) ‘Steve Hilton: ‘I’m Rich, But I Understand the Frustrations People Have’, The Guardian, 15 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/apr/15/steve-hilton-im-rich-but-i-understand-the-frustrations-people-have (Accessed: 15 April 2017).

Armytage, W. (1958). ‘The Chartist Land Colonies 1846–1848’, Agricultural History, vol. 32, №2, April, p. 87–96.

Attwood, T. (1839) ‘National Petition — The Chartists’, Hansard: House of Commons Petitions, 14 June, 48, c.222–227. Available at: http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/chartists/case-study/the-right-to-vote/the-chartists-and-birmingham (Accessed: 13 April 2017).

BBC (2015) Election 2015: What Difference Would Proportional Representation Have Made? Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/election-2015-32601281 (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

BBC (2017) Brexit: Environmental Standards Could be Eroded Warn Peers. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-38959996 (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Bloemenkamp, R. (2017) ‘A Robot Tax: Fair Measure or Unnecessary Hindrance?’, The Market Mogul, 1 March. Available at: http://themarketmogul.com/robot-tax-fair-measure-unnecessary/ (Accessed: 15 April 2017).

Bordeau, C. and Wilkin, P. (2015) ‘Public Participation and Public Services in British Liberal Democracy: Colin Ward’s Anarchist Critique’, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2015, vol. 33.

Butler, P. and Asthana, A. (2017) ‘Welfare Shakeup Will Push a Quarter of a Million Children Into Poverty’, The Guardian, 2 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/apr/02/welfare-shakeup-will-push-a-quarter-of-a-million-children-into-poverty (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Carrington, D. (2017) ‘London Breaches Annual Air Pollution Limit for 2017 in Just Five Days’, The Guardian, 6 January. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2017/jan/06/london-breaches-toxic-air-pollution-limit-for-2017-in-just-five-days (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Chase, M. (2003). ‘Wholesome Object Lessons: The Chartist Land Plan in Retrospect’, The Historical Review, Vol. 118, No, 475, February, p. 59–85.

Chase, M. (2007) Chartism, a New History. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

City of London Corporation. (1816) ‘National Petition — The Chartists’, Hansard: House of Commons Petitions, 14 June, 48, c.222–227. Available at: http://www.historyhome.co.uk/c-eight/l-pool/incometa.htm (Accessed: 13 April 2017).

Collins, J-R. (2016) ‘Why You Can’t Afford a Home in the UK’, Medium, 16 February. Available at: https://medium.com/@neweconomics/why-you-can-t-afford-a-home-in-the-uk-44347750646a (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Donald, A., Moore, R., Self, J. and Williams, A. (2016) From Plazamania to Garden Bridge: Why the Fuss About Public Space? [Panel discussion], Institute of Ideas, 19 June. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VFv3imN-0Go (Accessed: 12 April 2017).

Elliot, L. (2017) ‘Robots to Replace 1 in 3 UK Jobs Over Next 20 Years, Warns IPPR’, The Guardian, 15 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/apr/15/uk-government-urged-help-low-skilled-workers-replaced-robots (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Ellson, A. (2017) ‘Wealthy Professionals Forced to Rent Squalid Homes’, The Times, 7 March. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/352bedbc-02a0-11e7-ae09-71f14792998a (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Engels, F. (1845) Conditions of the Working Class in England. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/condition-working-class-england.pdf (Accessed: 12 April 2017).

Engels, F. and Marx, K (2010) Collected Works, Volume 6 Marx and Engels 1845–48. Edited by Cohen, J., Cornfirth, M. and Dobb, M. Lawence & Wishart. Available at: http://www.koorosh-modaresi.com/MarxEngels/V6.pdf (Downloaded: 18 January 2017).

Fairlie, S. (2009). ‘A Short History of Enclosure in Britain’, The Land, issue 7, Summer.

Fishwick, Z. and Fishwick, C. (2016) ‘Conditions That Caused English Riots Even Worse Now, Says Leading Expert’, The Guardian, 5 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/aug/05/conditions-that-caused-english-riots-even-worse-now-says-leading-expert (Accessed: 18 April 2017).

Foges, C. (2015) ‘Down With Old Fashioned, Useless Protests’, The Times, 16 November. Available at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/down-with-old-fashioned-useless-protests-tx56ktr3fn8 (Accessed: 9 April 2017).

Frost, J. (1839). (untitled), Northern Star, 6 April.

Gavin, H. (1848) Sanitary Ramblings, Being Sketches and Illustrations of Bethnal Green. Available at: http://www.victorianlondon.org/publications/sanitary-3.htm (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

German, L. & Rees, J. (2012) A People’s History of London. London and New York: Verso.

Hern, A. (2017) ‘Uber’s Head of Communications Quits Scandal-Hit Cab App’, The Guardian, 12 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/apr/12/ubers-head-of-communications-quits-scandal-hit-cab-app (Accessed: 15 April 2017).

Howkins, a. (2002). ‘From Diggers to Dongas: The Land in English Radicalism, 1649–2000’, History Workshop Journal, №54, Autumn.

Jack, I. (2016) ‘The Garden Bridge is an Oddity Born of the Chumocracy’, The Guardian, 21 May. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/may/21/garden-bridge-chummocracy-sadiq-khan (Accessed: 10 April 2017).

London Working Men’s Association. (1838) The People’s Charter. London: London Working Men’s Association.

Long Road to Change (2017) BBC Radio 4, 8 April. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08lfbh9 (Accessed: 10 April 2017).

Marshall, P. (1984) William Godwin. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Marston, R. (2016) ‘Gig Economy All Right for Some as up to 30% Work This Way’, BBC, 10 October. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-37605643 (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Martin, W. (2017) ‘The Gig Economy has Created a Strange New Problem in Britain’s Labour Market’, Business Insider, 17 April. Available at: http://uk.businessinsider.com/gig-economy-jobs-are-failing-to-stimulate-wage-growth-2017-4 (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Mayhew, H. (1861) London Labour and the London Poor. London: Griffin, Bohn and Company. Available at: https://archive.org/details/londonlabourand01mayhgoog (Accessed: 12 April 2017).

Media Reform Coalition (2015) Who Owns the UK Media? Available at: http://www.mediareform.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Who_owns_the_UK_media-report_plus_appendix1.pdf (Accessed 18 April 2017).

Milleris, H. (2016) The 1816 Repeal of the Income Tax. Available at: https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/petitions-committee/petition-of-the-month/war-petitions-and-the-income-tax/ (Accessed: 14 April 2017).

Minton, A. (2017) Big Capital. London: Penguin.

Monbiot, G. (2016) How Did We Get Into This Mess? Politics, Equality, Nature. London: Verso.

Montgomery Martin, R. (1833) Taxation and the British Empire. London: Effingham Wilson.

Moore, R. (2016) Slow Burn City, London: Picador.

Pain, T. (1795) Agrarian Justice. Available at: http://public-library.uk/ebooks/10/51.pdf (Accessed: 17 April 2017)

Peck, T. (2016) ‘Theresa May Admits Full Extent of Britain’s Toxic Air Crisis’, The Independent, 12 April. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/prime-minister-theresa-may-admits-full-extent-of-britains-toxic-air-pollution-crisis-fourth-biggest-a7680031.html (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Prickett, K. (2016) ‘Littleport’s Hunger Riots: Descendants Mark 200th Anniversary’. BBC, 28 May Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-36276197 (Accessed: 12 April 2017).

Raychaudhuru, A. (2016) ‘Uber, The “Gig Economy” And Trade Unions’, The Huffington Post, 1 November. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/anindya-raychaudhuri/uber-the-gig-economy-and-_b_12727752.html (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Roberts, M. (2009) Political Movements in Urban England, 1832–1914. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rowe, D. (1968). ‘The Failures of London Chartism’, The Historical Journal, xi, 3, Fall, p. 472–487.

Ryan, F. (2015) ‘By Rebranding Child Poverty, the Conservatives Think They are Saving the Poor from Themselves’, New Statesman, 25 June. Available at: http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2015/06/rebranding-child-poverty-conservatives-think-they-are-saving-poor-themselves (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Sandbrook, D. (2017) ‘Uber, Cameron’s Chumocracy and a Corrupt Culture of Entitlement’, The Guardian, 17 April. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-4417354/Uber-Cameron-s-chumocracy-culture-entitlement.html (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Searby, P. (1968). ‘Great Dodford and the Later History of the Chartist Land Scheme’, Agricultural History Review, xvi, 1, p. 32–45.

Sheffield, H. (2017) ‘Startups Spy an Opportunity in the Power of AI and Automation’, Independent, 10 April. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/Business/indyventure/ai-startup-luminance-pwc-robot-employment-a7675911.html (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Standing, G. (2016) Changing Utopia — or What Guy Standing Learned From the Lady of the Future [lecture]. Octoberdans 2016, 25 October. Available at: https://vimeo.com/191790608 (Accessed: 17 December 2016).

Stromberg, J. (1995). ‘English Enclosures and Soviet Collectivization: Two Instances of an Anti-Peasant Mode of Development’, The Agorist Quarterly, no. 1, Fall, p. 31–44.

Thorne, C. (1969) Chartism, a Short History. London: MacMillan and Co. Ltd.

Tiller, K. (1985) ‘Charterville and the Chartist Land Company ‘, Oxoniensia, L, p. 251–66.

Topple, S. (2016) ‘The Housing and Planning Bill Reveals how Little Tory MPs Think of the Public’, The Independent, 13 January. Available at: http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/the-housing-and-planning-bill-reveals-how-little-tory-mps-think-of-the-public-a6809951.html (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

UK Government and Parliament Petitions (2016) EU Referendum Rules triggering a 2nd EU Referendum. Available at: https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/131215 (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

UK Political Info (2015) General Election Turnout 1945–2015. Available at: http://www.ukpolitical.info/Turnout45.htm (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Vansittart, N. (1816) ‘National Petition — The Chartists’, Hansard: House of Commons Petitions, 14 June, 48, c.222–227. Available at: http://www.historyhome.co.uk/c-eight/l-pool/incometa.htm (Accessed: 13 April 2017).

Wainwright, O. (2016) ‘A Wholesale Power Grab: How the UK Government is Handing Housing Over to Private Developers’, The Guardian, 5 January. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/architecture-design-blog/2016/jan/05/housing-and-planning-bill-power-grab-developers (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Watt, P. & Minton, A. (2016) London’s Housing Crisis and its Activisms, City, 20:2, 204–221.

Walport, M. (2017) ‘Rise of the Machines: Are Algorithms Sprawling out of our Control?’, Wired, 1 April. Available at: http://www.wired.co.uk/article/technology-regulation-algorithm-control (Accessed: 15 April 2017).

IMAGE SOURCES

Gavin, H. (1848) Fictional Slum. Available at: http://www.victorianlondon.org/publications/sanitary-3.htm (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Green Party (2014) Photograph of Pollution in London. Available at: https://london.greenparty.org.uk/news/2014/04/09/air-pollution-how-many-more-must-die-before-politicians-act (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Kilburn, W. (1848) The Chartist Meeting on Kennington Common. Available at: https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/2932484/the-chartist-meeting-on-kennington-common-10-april-1848 (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

London Working Men’s Association (1839) The People’s Charter. Available at: http://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/21cc/struggle/chartists1/historicalsources/source4/peoplescharter.html (Accessed: 13 April 2017).

Media Reform (2015). Graphic Showing UK Newspaper Circulation and Revenue. Available at: http://www.mediareform.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Who_owns_the_UK_media-report_plus_appendix1.pdf. (Accessed: 18 April 2017).

Mistletoe, J. (unknown date). Photograph of a Chartist Cottage, Great Dodford. Available at: https://uptheossroad.wordpress.com/2014/12/31/great-dodford. (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Oxford Economics (2016) Graph of Unemployment and Wage Growth. Available at: http://uk.businessinsider.com/gig-economy-jobs-are-failing-to-stimulate-wage-growth-2017-4. (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Slack, J. (1819) Handkerchief Representing the Peterloo Massacre. Available at: https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/handkerchief-representing-the-peterloo-massacre (Accessed: 13 April 2017).

Southwarknotes (2015). Image Showing Estate Regeneration in Southwark. Available at: https://southwarknotes.wordpress.com/2015/02/21/regeneration-is-violence. (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

The Northern Star (1839) Newspaper Front Page. Available at: http://www.bl.uk/learning/citizenship/campaign/myh/newspapers/gallery1/paper2/northernstar.html. (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Unknown cartographer (1889). Map of Great Dodford. Available at: https://uptheossroad.wordpress.com/2014/09/08/what-is-life-without-liberty. (Accessed: 17 April 2017).

Unknown designer (1848) Chartist poster. Available at: http://protesthistory.org.uk/the-story-1789-1848. (Accessed: 17 April 2017)

Unknown photographer (1990). The Poll Tax Riots. Available at: https://flashprojects.wordpress.com/2011/03/30/50-years-of-youth-protest. (Accessed: 17 April 2017)