Coin Street Community Builders: Has the co-op vision been abandoned?

Essay2018

INTRODUCTION TO THE SITE

Waterloo is located in central London on the inside curve of the Thames, within walking distance of most of the capital’s most well-known and celebrated commercial, political and public sites. As a site for study it has witnessed first-hand the widely documented phases of London’s growth, change and processes of regeneration through history. As such, it is useful to offer a short introduction to the Waterloo area by way of setting historical context for the political, social and architectural landscape from which Coin Street Community Builders (CSCB) was born. A more in-depth history of the area leading up to the 1980s is provided by Street (2011, p. 105)

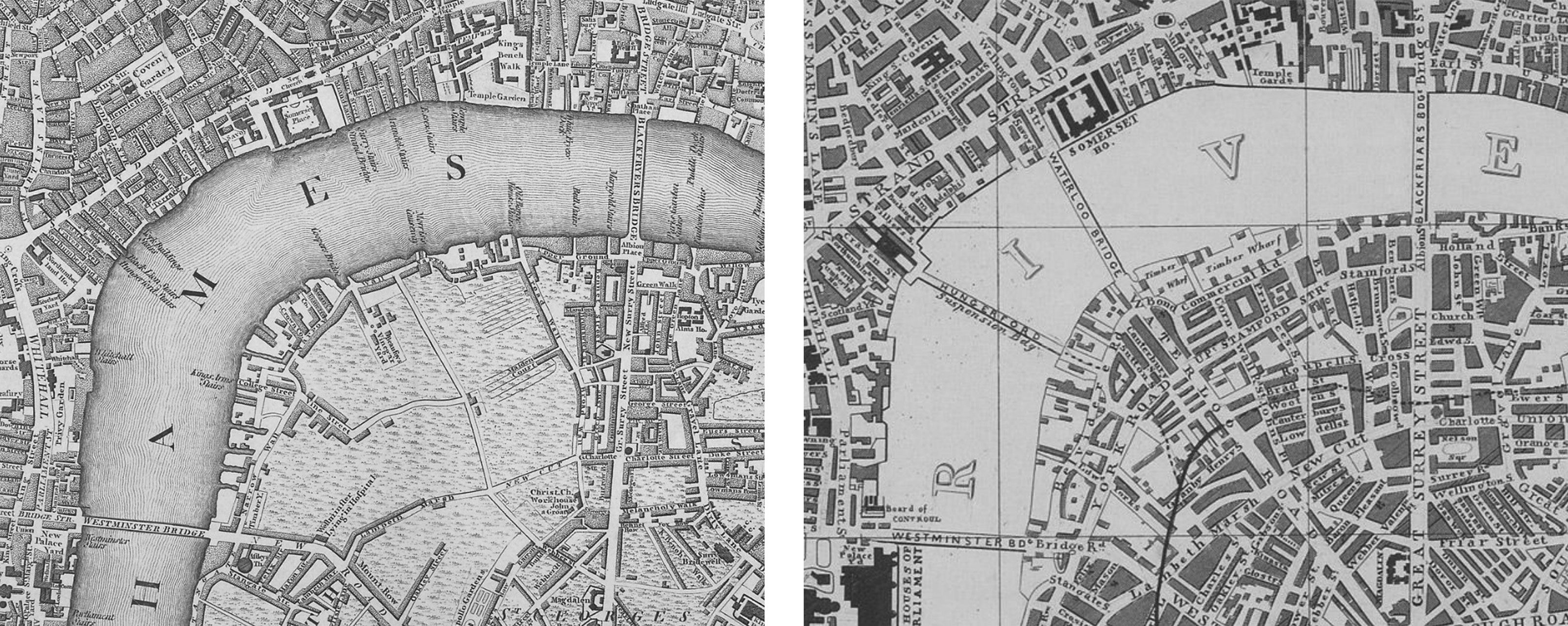

The study site sits between two bridges, Blackfriars Bridge to the west which opened in 1769 and Waterloo Bridge which opened in 1817. The construction of the former meant that by the end of the 18th century the marshy ground was becoming increasingly drained, initially for agricultural purposes and then emergent industries. A sole vinegar works is listed on a 1797 map (Wallis, 1797) but fifty years later the area had been completely built over with industrial units and working class housing behind wharves onto the river (Payne, 1846). This was reinforced by the extension of the railway to the area in 1848, the industrial revolution leading to a dense packing of factories, including the Liebig Extract of Meat Company which left its legacy in the area with the OXO Tower (Baeten, 2000).

Image 1: Waterloo area in 1769 (left, Wallis) and 1847 (right, Payne)

Image 1: Waterloo area in 1769 (left, Wallis) and 1847 (right, Payne)

Through the 20th century a number of regeneration plans have considered the area (see Baeten, 2000; Law et al., 2009). In 1915 London County Hall was constructed, though the private developments it was intended to act as catalyst for never followed. In 1943 Abercrombie proposed the South Bank to become home to a “Great Cultural Centre” as well as corporate HQs and other entertainment spaces with a fifty-years timescale. The first implementation of this was the Festival of Britain in 1951 which displaced a local residential community:

“Streets of terraced houses which had survived Hitler’s bombs fell to the Festival’s demolition contractors. The bailiffs had to be called in to forcefully evict some of the families but mostly people just accepted that the Authorities would do what they wanted and that was that.” (Tuckett, 1988)

It was hoped businesses would move into the space cleared for the cultural event, though take-up was low with Shell being the only major new employer and IBM and others following later. The area suffered post-industrial decline, which saw not only London’s docking trade disintegrate but also the ancillary and related trades connected to it, and as the businesses closed so people left the area. By the mid-1970s the population had fallen from 50,000 to 5,000, constant with a pattern of 1970s de-population of the centres which saw Greater London suffer net loss of 750,000 residents over the decade (Stewart, 2013, p. 80). Jacobs (1988) writes:

“As industry has fled the cities, people have followed. Left behind are those for whom capital no longer has need: the older men with redundant skills, the un- skilled and unemployed, many of them Black; the poor, the sick and the old, in rented housing which makes them immobile, and with no money to improve the derelict landscapes in which they find themselves.”

Social inequality and a lack of social housing also fed into the heightened inner-city atmosphere, presenter presented by politics and media as a space of destitution, decay, crime and drugs (Jacobs, 1988). Housing in Lambeth, as with all inner city areas, was in short supply. After Thatcher took power in 1979 the council sector of housing began to shrink with the 1980 right to buy scheme and removal of central funding for replacement property. It was this political and aesthetic landscape which presented Waterloo as tabula rasa for developers who were looking for speculative building plots for the overspill from the City offices north of the river.

THE FORMATION OF COIN STREET COMMUNITY BUILDERS

Shortly after completing Paris’ Centre Pompidou in Paris with Renzo Piano and the Lloyd’s of London corporate headquarters architect Richard Rogers developed a major office scheme for the Coin Street area (Rogers Stirk Harbour, no date-c, no date-d and no date-e) on behalf of developers Greycoats and Vesty. Including a ‘glazed street’ linking Waterloo Station through to the riverside OXO Tower (image 2), blocks equivalent to “a Centrepoint tower every 200 yards” sat along its path (Jeffrey, 1997).

The recognisable OXO Tower would have been demolished to make way for a 14 storey office building at the head of a new footbridge linking to the City north of the river. It was, in the words of Brindley, Rydin and Stoker (1989, p. 82) “a purely commercial venture which offered some social amenities as a planning gain, and was based on conventional institutional sources of funding”. Rogers also cited his proposals, and the proposed crossing, as rooted in commercial profit:

“The rents on [the South Bank] of the river are £12 per square foot, the rents on [the north] of the river are £24 a square foot. Maybe if you put a bridge you can add £2 a square foot when it’s linked to the north… So where does the bridge come from? It comes from the evening out of the rent between the north and the south banks, it’s not something which is just thrown in.” (Rogers, 1982)

Hatherley (2014) stated that Rogers fighting on the side of developers against a community-led ‘left-leaning Housing Association’ was “one of the definitive dates when ‘radical’ architecture and radical politics could be seen to have truly divorced”.

Image 2: Richard Rogers scheme for the Coin Street site (Rogers, no date-e)

Image 2: Richard Rogers scheme for the Coin Street site (Rogers, no date-e)

The Rogers scheme was the final of a number of massive commercial proposals for the area, all of which had been repeatedly opposed by the remaining residential population who saw their history and community under pressure from the free-market forces who saw only opportunity for financial profit (image 3). Towers (1998, p. 97) relates this community battle for the ownership and management of the Waterloo area to other contemporary London battles between the public and developers reasoning that “confrontation between mammon and community” had become more commonplace following successful activism against proposed London Ringway motorway and Covent Garden development in the 1970s, both of which would have destroyed local communities.

Image 3: 1980s protest by the Association of Waterloo Groups (Coin Street, 2016d)

Image 3: 1980s protest by the Association of Waterloo Groups (Coin Street, 2016d)

In 1984 the GLC and the Greater London Enterprise Board awarded the community a £1m mortgage with which to purchase the collection of sites (image 4) from the GLC for a greatly reduced rate of £750,000 (Brindley, Rydin & Stoker,1989; Baeten, 2009), two years before Thatcher disbanded the GLC and six other metropolitan counties. Stewart (2013, p. 436) describes this as a sign of “Whitehall’s growing conviction that quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations could make a better job of strategic planning and encouraging investment than another layer of elected politicians” and the Coin Street site sale was a final symbolic gesture, marking the moment that the third sector, partnerships and the private sector were given greater control over the nature of development.

Image 4: Coin Street Community Builders land as purchased from the GLC, highlighted in yellow by author overlaid onto copyright Google Map.

Image 4: Coin Street Community Builders land as purchased from the GLC, highlighted in yellow by author overlaid onto copyright Google Map.

The 1980s saw these neoliberal politics began to drastically shape the aesthetics of the city. In Rebel Cities, David Harvey (2012, loc. 659) writes that “neoliberal urban policy concluded that redistributing wealth to less advantaged neighbourhoods… was futile, and that resources should instead be channelled to dynamic “entrepreneurial” growth poles.” This has been described by Raco, Street and Trigo (2013) as “the role of the state [becoming] one of organising projects aims and objectives and funding private actors to undertake these tasks”.

Neil Smith (1979) was writing about US cities’ gentrification of this period, but there are parallels to be drawn to London of the same period when he states:

“The so-called urban renaissance has been stimulated more by economic than cultural forces. In the decision to rehabilitate an inner city structure, one consumer preference tends to stand out above the others-the preference for profit, or, more accurately, a sound financial investment.”

These were the social conditions which led to the formation of CSCB by local action groups, under the umbrella “Association of Waterloo Groups”. The Rogers scheme was a neoliberal speculative commercial venture while CSCB proposed “a thoroughgoing community project, which would provide low-rent housing for local people in need, funded either by the local authorities or a co-operative housing association” (Brindley, Rydin and Stoker, 1989, p. 82).

The story of how the remaining community members of a post-industrial, working class community joined together to purchase plots of land long desired by commercial property developers is documented fully in Brindley, T., Rydin, Y. and Stoker, G. (1989), published shortly after the first housing co-op was opened on the site.

As years passed CSCB continued its co-operative residential project, and this initial favourable reporting of the project continued in much the same vein with little updating of the story to reflect changes, developments or the different political times. Frequently, literature on CSCB is reduced to a more digestible nugget, as in Awan, Schneider. and Till. (1989) in which the backstory and complexities are reduced to just a few paragraphs formed to deliver a positive message of alternative approaches to shaping a city. In popular media, CSCB is generally reduced even further to become a simplistic shorthand to counter the more prevalent development stories, eg Glancey (2002).

Taking the subject a little deeper is Bibby (no date), while Coupland (1997, p. 244) considers the financial implications of starting a new co-operative venture, especially within CSCB’s second phase which included the restoration of the OXO Tower Building into a mixed-use venture incorporating a Harvey Nichols restaurant. The wider South Bank, including CSCB, has been used frequently as a case-study for other cities or academics considering examples of post-industrial regeneration (see Law et al., 2009) and there is a source written by Iain Tuckett (1988), founding member of CSCB, explaining the history of the site and how CSCB came into being which he updates the project at the turn of the millennium (2001).

Some writing does exist which considers CSCB in more depth and with more criticality, including in Towers (2003) which suggests that years of adversarial conflict between the community group and developers resulted in low-density development which doesn’t “realise the full potential of the sites” with a suburban vernacular. Towers states the CSCB development could have been different if the local forum had been more representative of the community with more profound debate about the aims and practice of the project.

These are also key points picked up in the writing by Baeten who takes a far more critical view of the CSCB history than most. His first paper (2000) considers CSCB in the years after formation and in light of Margaret Thatcher’s dissolution of the Greater London Council [GLC] in 1986. Baeten outlines the new methods of distribution of (a smaller pot of) regeneration funds from central government via the City Challenge Fund of 1991 and the Single Regeneration Budget Challenge Fund [SRG] of 1994, discussing the formation of partnerships by local organisations to form stronger applications for new funding streams.

Of particular importance is the South Bank Employers’ Group [SBEG], organised by CSCB in 1995 to partner with local political figures and neighbouring major employers including Shell, UBM, ITV, Ernst & Young and Sainsbury’s — the first of numerous partnerships formed by or with CSCB from the local to London-wide — and CSCB currently list 18 partnerships on their website (CSCB, 2016). Recently, SBEG formed a partnership with the neighbouring WeAreWaterloo Business Improvement District [BID] to “seek the devolution of a range of council services into local management, including street cleansing and enforcement” (Stephenson, 2015, p. 37). This represents the ultimate example of the state’s role becoming “organising projects aims and objectives and funding private actors to undertake these tasks”, as Raco, Street and Trigo (2013) quoted earlier.

When Baeten revisits CSCB eight years later (2009) he re-affirms his research from the earlier paper, and illustrates how SBEG have become the single controlling authority of the South Bank area, “deciding over all the important aspects of regeneration”. He goes on to explain how the developed partnerships on the South Bank have served to “neutralise dissent” and “uniting all groups in one partnership effectively forecloses meaningful disagreement and dispute, and therefore democracy” (Beaten, 2009, p. 247).

The most successful strategy for partnerships to gain SRB funding is through rational communications, strategic front and calculated targets which are acceptable to the distributing government and associated funding bodies. Consequently, Baeten posits, this creates “the end of politics, death by partnership” (Baeten, 2009, p. 248) due to non-partnership voices and demands being ostracised and ignored, deemed to be “politically motivated” or “irrational”. To create a singular voice for an area’s development the tightening control of a partnership forces out the voices not included.

Baeten states that this post-political high-level partnership planning developed after the New Labour government of 1997 embraced SRB culture “to a level the Conservatives could not have imagined” (Baeten, 2009, p. 247). This is picked up on by Street (2011) and analysed in more depth, using SBEG between the years of 2007 and 2010, the last years of the New Labour government, as a case-study. Street articulates the political landscape that the saw New Labour heighten Conservative neoliberal policies, in particular the concentration and movement of services and social amenities into the third sector (Street, 2011, p. 33).

Raco, Street and Trigo (2013) also discuss the various strata of governance in the South Bank area and contemplate the implications of so many partnerships acting as agents in the “liminal governance spaces in between the private sector and the formal public planning process”. They argue that this “can be seen as part of a wider legitimation exercise in which they help developers to overcome local opposition” and that they “frame community responses in a managed way and limit the possibilities for outright opposition”.

THE RETURN OF RICHARD ROGERS & THE NEOLIBERAL SHIFT

A major shift between the Conservative government policies of 1979–97 and those of New Labour which followed was the relationship to the inner-city, adopting an Urban Renaissance approach led by Richard Rogers with the intent of revitalising urban centres by drawing populations, and money, back into the vacated post-Industrial, post-Conservative areas (Moore, 2016, p.306). This programme is illustrated by the published documents Towards an Urban Renaissance (Urban Task Force, 1999), Our Towns and Cities: The Future, Delivering an Urban Renaissance (DETR, 2000) and Towards a Strong Urban Renaissance (Urban Task Force, 2005) written by the Urban Task Force chaired by Rogers and set up by deputy Prime Minister John Prescott. These were key documents in an urban regeneration prevalent in London since 2000, formulating much of the approach and language which is still used to in the process of ‘place-making’, delivering ‘regeneration’ and creating ‘investment opportunities’.

In 2000 the Labour government reintroduced local governance into the capital with the Greater London Authority [GLA] with former leader of the GLC Ken Livingstone heading it up as the first leader as Mayor of London. In 2001 Rogers was invited by the mayor to set up The Architecture and Urbanism Unit. Livingstone was to take a key interest in architecture and the built environment, but in this second term leading the capital he took a more neo-liberal approach to development (see Carmona and Wunderlich, 2013).

“Ken Livingstone as mayor formed a very close relationship with the City of London and property interests, and his approach was fully compliant with the hegemonic vision for world city growth… He showed no residue of his 1980s attempts to protect community interests.” (Edwards, 2010)

In the years since his South Bank scheme was usurped by CSCB, Rogers’ architecture has, parallel to Livingstone’s politics, arguably softened in radicalism as he has shifted towards a role as designer-for-hire for super-rich clients, most recently evidenced in his Neo Bankside and Riverlight luxury housing schemes (Rogers Stirk Harbour, no date-a and no-date-b). His 1997-onwards period has been described by Murphy (2012, p. 92) as “Blairite-modern, welcoming and posh but lacking in both substance or morals” and Owen Hatherley goes further:

“Rogers’s recent legacy is a series of beautiful, unique and fascinating machines producing nothing save for money; and a series of texts that imagined a better city while refusing to admit that such a thing might involve questions of power and conflict. The firm he founded will endure as creators of the former, but the real and terrible consequences of the latter will not be solved by them.” (Hatherley, 2013)

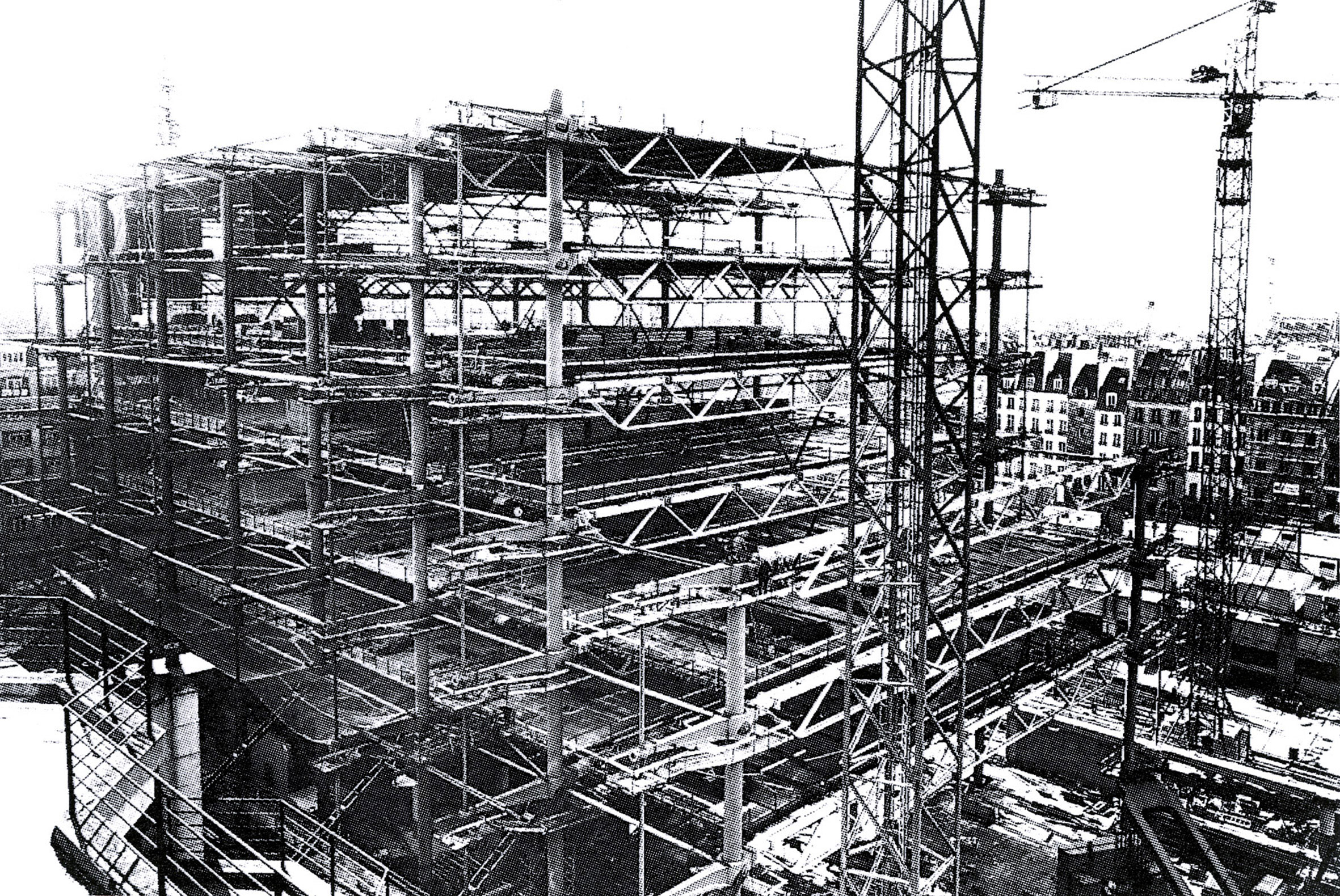

Rogers’ current neoliberal profiteering via super-rich developers may seem at odds with his self-proclaimed socialist origins launched on the spectacular, radical Centre Pompidou in Paris. He envisaged a non-hierarchical “democratic place for all people and the centrepiece of a regenerated quarter of the city” (Rogers Stirk Harbour, no date-c) intended to capture the sense of 1968’s near-revolution (Rogers, 2013) and “not be a monument, but a festival, a large urban toy” (Rogers, quoted in deRoo, 2006, p. 178).

Image 5: Richard Rogers’ Pompidou Centre under construction in the Beaubourg area of Paris (Rogers, no date-c)

Image 5: Richard Rogers’ Pompidou Centre under construction in the Beaubourg area of Paris (Rogers, no date-c)

His art museum had a different role for the state: by locating the project in the working class neighbourhood of Beaubourg (image 5), President Pompidou claimed he was democratising culture through shifting social bias of Parisian museums, while a key part of the development enabling the demolition of parts of the area (deRoo, 2006, p. 170). As such, this presentation of a socially enhancing, democratic project as response to the uprisings of 1968 — which Harvey (2008) notes were partially borne from protests against the Left Bank Expressway and high-rise buildings destroying communities — was a deliberate tool of gentrification and suppression of the working class community through an artwashing premise.

Despite Rogers’ intentions, Rayner Banham argues the Pompidou was “a very permanent monument”, and it has monumentalised the process of cultural architecture as urban regeneration, setting a precedent of iconic cultural placemaking (Murphy, 2012, p.114). This role as icon to aid the image of a world-city (deRoo, 2006, p 168) is a model which has been copied freqiently under the neoliberal guise of “urban regeneration” and “gentrification”, most famously with the Bilbao Guggenheim and in London with Tate Modern (Worsley, 2002; Nixon et al., 2001) as well as with the Garden Bridge which we will encounter later.

COIN STREET & THE PULL OF THE VERTICAL

Three years after Rogers’ Architecture and Urbanism Unit was created Livingstone published The London Plan (2004) in which Waterloo was listed as one of 28 Opportunity Areas earmarked for high-density development with tall buildings (see Edwards, 2010; Raco, Street and Trigo, 2013).

“South Bank’s past, that of the promise of office towers eliminating a once vibrant residential and industrial community at the heart of London, is haunting the South Bank’s immediate future. Towers are emerging again in the architects’ drawings for the South Bank, ironically commissioned by the CSCB who were once fighting tower development” (Baeten, 2009)

Image 6: The proposed Doon Street Tower (Spurr, 2015)

Image 6: The proposed Doon Street Tower (Spurr, 2015)

Baeten was referring to the 2005 proposal of Doon Street Tower to be built on land behind the National Theatre (image 6), used as a car park for the intervening years. Proposed by CSCB (who were, remember, formed to oppose high-rise and non-community development) it was originally intended to be 173m tall, with this reduced to 144m after heritage objections (Kufner, 2011 p. 173), and was to comprise of 329 luxury apartments all for sale at a market value. As a public offering a 25m swimming pool would be included, which CSCB argue is core to their community ideals; one of the CSCBs many partnerships, the South Bank Partnership [SBP], polled residents and workers in the South Bank area in 1999 (Ipsos Mori, 2009) with a pool top of their wish-list.

Street (2011), writing after the proposals developed further, considers the Doon Street project as a form of managing the community. It could be argued that such opinion-polls guide the thoughts of a community, rather than genuinely recording desires and needs. The question asked was whether respondents were satisfied by the current swimming pool provisions in the area, though as there were no existing pools then a low percentage can pretty much be guaranteed. Selective questioning can lead to desired answers and acts to lead an audience:

“Such practices evidence the careful management of community, wherein the goal is to, through the line of least resistance, “get things done”. This Is a finding that resonates with New Labour’s contention that, In the delivery of local services, ‘what matters is what works in giving effect to our values’” (Street, 2011, p. 297)

Questions should be asked of which “community” CSCB is now acting for — their co-op community of residents or the wider community of partnerships. The poll sampled the wider north Lambeth area of SBEG and SBP and included tourists and local employees, a far wider sample than the CSCB sites even though they are both funding the project and claiming it to be for their community (Ipsos Mori, 2009, p. 7–11). Though other SBEG members were key in the project receiving planning permission and passing through a public inquiry. Tuckett stated:

“All members of this not-for-profit company are local residents who have a shared vision for the future of London’s South Bank and who have led the area’s transformation over the past 20 years. That means recognising all of the needs of our community, as well as understanding how the area can contribute to London’s wider economy and environment.” (Ball and Tuckett, 2007)

Worth considering is Tuckett’s line “All members of this not-for-profit company are local residents”. Half of the current eight-member CSCB are co-op residents, though Tuckett himself has never lived in the project (King, 2017), but is understood to own terraced property in a neighbouring, highly sought after, group of streets which have seen astonishing property value hikes over the past twenty years. Fewer affordable and social properties and more corporate, entertainment construction in the area would only push the value of these higher.

Through the creation of uncritical partnerships with other local actors it could be said that CSCB are now acting on behalf of a different community to the local co-op residents they were set up to act for. In interview, a Coin Street resident told me that it had angered co-op residents “because obviously it’s not social housing” and that CSCB “haven’t fulfilled what they set out to do” (Coin Street Resident, 2016). Michael Ball of local grass-roots Waterloo Community Development Group adds:

“Ultimately, this has come about because Coin Street Builders is not accountable. Nobody there is elected and it does not answer to the community or to the Housing Corporation.” (Ball and Tuckett, 2007)

There appears to be differing readings of the word “community” between Tuckett and critics which are worth considering as we understand changes CSCB has gone through with numerous partnerships.

“‘The community’ in the days of community planning was the impoverishing community of mainly working-class residents who were deprived of affordable housing and job opportunities. ‘The community’ in the days of partnership planning is a political construction serving particular interests: through taking on board the mighty local business community and its employees in ‘the community’, regeneration projects might be more eligible for funding, but they also tend to become dominate by the private sector’s particular interest, while ‘the local residents community’, ‘the local poor’, or ‘the unemployed’ almost have become a rhetorical device to demonstrate the social benevolence of regeneration projects.” (Baeten, 2009)

In Stephen Graham’s recent study of the city, Vertical, he states that in 2013 85% of all inner London housing purchases in inner London were from non-UK nationals, and most property was in the “higher and super-higher” price brackets (Graham, 2016, p. 201). His chapter Housing: Luxified Skies offers a good rendering of the global urban growth in vertical, luxury living, commenting that it represents “a process of the marketisation of land and real estate organise for the ‘housing’ of elite capital than for a city’s people (let alone a city’s poorer population).” (Graham, 2016, p. 177).

Tuckett would counter this by claiming Doon Street Tower was part of a strategy to help poorer urban residents. When suggestions that CSCB were no longer acting with social tenants in mind during the development of the Harvey Nichols OXO Tower restaurant, he stated:

“Unless as a social enterprise you are willing to cater for people with money, if you’re only going to cater for people in poverty, you will never get to viability. Any strategy that is sustainable has got to have something which brings in money and recycles it — it’s a Robin Hood approach” (Tuckett, quoted in Bibby, no date)

COIN STREET & THE PULL OF THE HORIZONTAL

A New Statesman article (Jeffrey, 1997) considering the CSCB completion of the OXO Tower renovation, and which resonates with the Doon Street Tower proposals a few years later, asks:

“Can the late-night junketing of the Ab Fab generation be tolerated by Oxo’s new residents? And how will Coin Street square its deals with Harvey Nicks with its supporters’ wider social needs?”

This couldn’t have been more prescient. In 1998 Joanna Lumley - an actor who played Patsy in Absolutely Fabulous, colloquially known as Ab Fab, a sit-com set in the world of over-the-top fashion culture lifestyles which Jeffrey thought may visit the OXO Tower restaurant - dreamt up a project which could have had huge implications for CSCB and London, the Garden Bridge (image 7).

Image 7: The proposed Garden Bridge (Heatherwick Studio, 2016)

Image 7: The proposed Garden Bridge (Heatherwick Studio, 2016)Originally a hypothetical memorial to Princess Diana sketched out with architect Nigel Coates and sent to the Diana Memorial Committee for consideration alongside over 10,000 other suggestions, it was proposed for near Westminster Bridge and included “flower sellers selling single blooms”, “container grown trees” and a café kiosk selling “very simple things like coffee, tea, apple juice and champagne” (Lumley, 2005). It never went further than an idea, however in 2002 Lumley was introduced to designer Thomas Heatherwick and the project grew in scope, scale, cost and at some point moved down-river to the CSCB site.

It went quiet until 2012 when the project suddenly gained traction after Boris Johnson, who had known Lumley since he was four years old, succeeded Livingston as Mayor. He received a letter from Lumley suggesting she and Heatherwick meet him to propose the Garden Bridge. Architecture critic Rowan Moore (2016, p. 379) succinctly outlines how the Garden Bridge passed through two suspicious procurements and unusual funding mechanisms to end up as a £185m project with £60m public finance. The story is complex and raises numerous concerns around public space, privatisation of the city, damage to heritage and environmental ‘greenwash’ and nepotism, all of which is outlined by opposition campaigns (Jennings, 2016; Thames Central Open Spaces, 2016).

The role of CSCB in the project remains less clear. Despite the fact that Lumley mentions in her 2005 biography that she had met with a “supportive” Iain Tuckett, CSCB state that they were only first approached about it in 2013 (Coin Street Community Builders, 2016b). They own the lease of the land on which the Garden Bridge would land and currently manage it as a public park surrounded by 30 mature London plane trees, all of which would have been removed for a commercial unit and public queuing space (image 8). The land formed of the public riverside walkway and greenspace which was laid out by CSCB’s first construction project using public GLC monies, and was key to their founding principles and convincing argument when battling Rogers’ commercial scheme.

Image 8: The existing South Bank park and avenue of trees (left, photography by the author) with the proposed commercial development with staircases to and queuing platform for the Garden Bridge (right, London SE1, 2016b)

In a twist of history, the residents of Coin Street formed a campaign group, Thames Central Open Spaces [TCOS] (image 9), to oppose the Garden Bridge, regularly protesting Iain Tuckett and the CSCB board at meetings and public events, calling for them to oppose massive anti-community development in precisely the same way Tuckett had done in the 1980s.

Image 9: TCOS protesting against the proposed Garden Bridge outside a CSCB Board meeting (London SE1, 2016)

Image 9: TCOS protesting against the proposed Garden Bridge outside a CSCB Board meeting (London SE1, 2016)

Referring to the Garden Bridge and Doon Street Tower alongside an alleged reluctance to complete initial plans for 400 co-op housing units, TCOS claim that CSCB have “lost their moral compass”:

“any idealised notions of neighbourhood cohesion in the 1980s has been eroded by greed and empire building for all the wrong reasons. CSCB have stopped listening to their own people. Their claims of acting in the interests of ‘elected representatives’ where the Garden Bridge is concerned is pure hogwash given that they are accountable to no one — except their own long-neglected community.” (TCOS, 2016)

Tuckett and CSCB suggested that despite owning the lease of the land, and thus legal final say on development, they should “accede to a scheme backed by elected politicians” (The Guardian, 2016) though under significant public and political pressure, not to mention the forceful and voal TCOS protests, CSCB appeared to reconsider. Lumley then stated that “Coin Street are very opposed to it” and Tuckett “hinted that the project would have to clear significant hurdles in order to win its final approval” (Hurst, 2016). In one of few public statements made, CSCB state:

“we have both a right and duty to ensure that the scheme only goes ahead if we can be satisfied that the promised benefits are delivered for the community we serve and its impacts mitigated” (Coin Street Community Builders, 2016c)

Again, this leads to ask which “community” CSCB were representing, their co-op residents or the SBEG and wider partnerships? The Garden Bridge Trust [GBT] were formed to deliver the project, and quickly joined both the South Bank and Northbank BIDs, thus positioning themselves to present the image of community participation whilst being in a strong negotiating position to work with local landowners and agents, reminding of Baeten’s (2009, p. 247) that “uniting all groups in one partnership effectively forecloses meaningful disagreement and dispute, and therefore democracy”.

Despite the South Bank BID including CSCB as a member, they told a 2016 Mayoral publication that they don’t “do much work with residential communities, although it fully recognises the need for residents to be aware of the BID and its work” (Durston, 2015). BID critic and author Anna Minton responded to this for the same Mayoral publication, stating:

“I cannot see why the [BIDs] do not involve residents. This is an organisation for businesses that recreates place in the image of business. That is a very different way of looking at the city” (Minton, quoted in Bacon et al., 2016, p. 20)

Again it could be read that CSCB were acting on behalf of the SBEG ‘community’ ahead of their residential co-op ‘community’, at least up until such strong opposition may have led to a rethink. If the Doon Street Tower’s privately purchasable luxury apartments saw a departure from CSCB affordable, working-class roots then the Garden Bridge suggested an apparent willingness to help create destination architecture for the global tourist and corporate stage, remote from their founding principles and against the wishes of their co-ops.

The Garden Bridge would have directly connected the South Bank BID with the Northbank BID, a corporate rebranding of the area around Temple station and along the Strand to Trafalgar Square. Just as, quoted earlier, the purpose of Rogers’ commercial proposed commercial scheme was to aid the “evening out of the rent between the north and the south banks” (Rogers, 1982), the Garden Bridge was similary a device of creating a capital parity for landlords benefit. However, by 2012 according to the Evening Standard the “tables have turned”, as “prime property on the Southbank now costs £1,700 per sq ft. On the newly christened Northbank… the rate is £100 cheaper” (Mount, 2014).

This private bridge would not only offer a (reverse) “evening-out” of rent but would have also offered direct access to the South Bank’s entertainment culture which the north bank had been eying greedily and seeking to appropriate, as architect Piers Gough had already noted (Taylor, 1996). In return the South Bank BID would have gained connection to the commercial renting of the north side of the river and, for both, an architectural ‘icon’ gives them a global stage with associated marketing and capital opportunities.

The Northbank BID is formed of almost entirely super-rich corporations from the global marketplace, finance industry and property development (Northbank BID, 2016). Speaking of BIDs in the aforementioned Mayoral publication, Minton says:

“you clear out the excitement, you clear out the diversity already existing [to] create a bland, duty-free departure-lounge environment and then you have to make it exciting and so you import some street theatre. That is not the way to create an exciting, diverse, democratic place, but doubtless it brings in big revenues for a certain kind of business.” (Minton, in GLA, 2015).

For the Northbank BID, with multi-million pound developments and global ambitions, some “street theatre” will not suffice. Instead, the ‘imported excitement’ was a £185m piece of urban place-making which Moore suggests favoured “the logic of big money, of contractors, investors and sponsors, over the particular, the specific and the local, not to mention common sense” (Moore, 2016, p. 387). The Northbank BID claimed that “we lack the lovely riverfront pedestrian area [the South Bank has] and the Strand lacks identity” (Durston, in Dare Hall, 2014). The Garden Bridge offers them a solution presented as the kind of project that Spencer describes in The Architecture of Neoliberalism as:

“[a] friction-free space supposed to liberate the subject from the structures of both modernism and modernity, to reunite it with nature, to liberate its nomadic, social and creative dispositions, to re-enchant its sensory experiences of the world” (Spencer, 2016, loc. 161)

To the offshore investor, the day-tripping tourist or the BID manager, the “imported excitement” is not something to be public, purposeful or cause friction. Instead, as the Garden Bridge offers, it should be the kind of architecture Jonathan Meades describes as parodically representative of this age:

“A new type of structure, characterised by its hollow vacuity, by its sculptural sensationalism, by its happy quasi-modernism, and by its lack of actual utility. Yet it possesses two definite purposes, to be instantly and arrestingly memorable, to be extraordinarily camera friendly. This type of structure is a sound-bite’s visual analogue. A sight-bite.” (Meades, quoted in Murphy, 2012, p. 114)

Mark Wilkinson of estate agents Knight Frank points out in the Financial Times that “The South Bank has had a head start, focused around Tate Modern, Neo Bankside and other key schemes” (in Dare Hall, 2014) while the he lists Northbank BID flats priced between £2.93 and £14 million pounds (image 10), pointing out that that “by the time the Northbank’s regeneration is complete” they will all have gone up in price due to constraints on stock and land. Rogers has frequently come out in support of the Garden Bridge, the most neoliberal of developments, (Rogers, 2014; Hopkirk, 2015; Cooper, 2016) and suggesting a close relationship between the two, Heatherwick frequently utilised phrases almost lifted word-for-word from Rogers’ descriptions of his 1980s Coin Street scheme.

Many questions have been raised about public finance and assets being used to aid the private Northbank BID developments, including from former London Assembly Member Darren Johnson who said local land and property owners would “be able to charge even higher rents to tenants, and command a higher price if they choose to sell their office space or flat, all without lifting a finger” (Johnson, 2015).

Image 10: Promotional montage for the 190 Strand, Berkeley Homes development in the Northbank BID (Berkeley Group PLC, 2016)

Image 10: Promotional montage for the 190 Strand, Berkeley Homes development in the Northbank BID (Berkeley Group PLC, 2016)

This would, of course, be the situation on both sides of the river and with CSCB increasingly appearing as property developers representing a local corporate community, rather than co-op managers and representative of an affordable rent community, they may have conflicted interests when deciding whether to allow the Garden Bridge to be constructed on their land or not. Heatherwick repeatedly states that London is “the thought leading capital of the world” and his Garden Bridge is evidently designed to impact on the global stage rather than local.

Aligning with Graham’s quote earlier about inner-London property being marketed to non-UK residents, the GBT regularly promoted their project in Asia in the search for backers, and the Northbank BID property brochures, often prominently featuring the Garden Bridge, were also heavily marketed in Asia and the Middle Easy. This is worth considering, as finances raised from the Garden Bridge commercial unit on CSCB land would have gone some way to helping finance the stalled Doon Street Tower development which, with its 329 luxury apartments increasing in value as an investment opportunity for the same offshore market as the Northbank targeted.

When urban partnerships, such as BIDs, work together they create a super-network of quasi-political organisations which can operate to near-enough run the city instead of elected democratic bodies. Between them these partnerships have the business, media, political and cultural connections to facilitate smooth planning applications, proposals and schemes as well as control or minimise democratic opposition. The Garden Bridge makes a direct horizontal connection between two of these partnerships, encompassing many others including the Cross River Partnership (2016).

Arguably the ‘local’ is subsumed within the network of partnerships which are all complicit in a greater agenda to position London as the free-market ‘world city’ that Rogers, Livingstone (from 2000), Boris Johnson and now Sadiq Khan all desire. This has developed throughout the neoliberal rise since the Thatcher:

“[Since the mid-1980s] London has expanded both its population and its share of national output with its business and political leaderships developing and pursuing the city’s development as ‘Global City’ or ‘World City’. These concepts became dominant in the period 1985–2000 when London lacked a metropolitan government, and were rarely challenged, eventually becoming firmly embedded in the planning of London when it resumed in 2000 under Ken Livingstone as mayor and Tony Blair as Prime Minister.” (Edwards, 2016, p. 228)

In his paper Gentrification as a Global Habitat, Davidson considers various ‘regeneration’ projects along the Thames, highlighting how the developers connect their projects to London’s “global spaces of culture” and present the idea of a “global London” (2007). The Northbank BID go one step further and desired abridge to directly link them to the South Bank and its culture, with the apparent complicity of the South Bank BID.

The Garden Bridge was ultimately not built, the opposition and numerous legal, financial and PR hurdles the GBT faced became insurmountable and in late 2017 the project was called off. However, on top of the huge expense to the public purse incurred there was also profound damage to the relationship of CSCB to its co-op residential community.

THE EFFECT UPON COIN STREET COMMUNITY BUILDERS

The two case studies of Doon Street Tower and the Garden Bridge indicate a growing gap between the management of CSCB and the residents, as well as an apparent shift in aspirations and plans since the 1980s. Baeten discussed this growing gap in his paper of 2009, and the years since which have seen both case study projects develop (but, crucially, not start construction) have only furthered his hypothesis:

“Partnership-style regeneration, although aimed at meeting social-economic needs in the area, has disempowered those who it claims to be working for. It has shifted the epicentre of urban regeneration power to unaccountable bodies which have harmed the already fragile base of local democracy.” (Baeten, 2009)

In their analysis of co-op housing schemes over time, Laing and Novy discuss the increasing lack of resident participation as a co-operative scheme gets older. They write that “residents are increasingly considered as ‘passive customers’ who need to be served and empowered by the housing organisation in a way that does not interfere with the principles of corporate management” (2014). The authors are considering German and Austrian co-ops, but there are parallels that can be read into CSCB. They continue:

“strategic partnerships with the local government [have] considerably weakened the cooperative character of individual housing organisations. Furthermore, recent liberalisation of housing regulation and changing market conditions favour corporate management approaches and concentration processes within the sector which lead to a further hollowing out of the cooperative principle of democratic member participation. As a result, residents are no longer able to effectively influence the governance of their housing organisations.” (Laing and Novy, 2014)

The partnerships CSCB have formed or joined may have opened up opportunities and investment for the organisation, but the neoliberal market pressures from surrounding sites as well as changing politics are putting the project under huge amounts of pressure. With the “world city” London now commanding such high prices for land and property, there is a perfect storm brewing in the Waterloo area where CSCB residents who are again feeling pressured by forces of gentrification, free-market economics and speculative building accompanied by icons of regeneration such as the Garden Bridge. Added to this they there is a feeling that CSCB are no longer fighting their corner and instead act as a commercial landlord:

“People have a fear of the landlord, it’s precarious. People feel they have to not rock the boat. People haven’t really understood that power is in their hands, in our hands.” (Coin Street resident, 2016).

Projects such as Doon Street Tower could be seen to compromise the promises that CSCB would use the site for their co-op community and for affordable housing. In an age when the limited stock of affordable and social housing is undergoing “estate regeneration”, including heavily in Lambeth and Southwark (where, incidentally, the Heygate Estate was ‘regenerated’ under the watch of Southwark’s Director of Regeneration, Fred Manson, currently Associate Director at Heatherwick Studio), the construct of CSCB co-ops as well as their physical buildings is under huge pressure.

Once empty plots get used up, which CSCB expect by 2024 (King, 2017), either by the initially planned co-op housing or by more Doon Street style towers, there will be instant pressure upon the existing 1980s low-rise co-op housing. May these be offered up for ‘regeneration’ as we have witnessed with social housing across the capital? Could the greenspaces between the existing blocks be infilled with ‘affordable housing’ at around 80% of market rate?

Will the co-ops even remain at their genuinely affordable levels? Ominously, talking about the first CSCB co-op development, Tuckett said “Its rents are fair rents, although obviously that situation is changing” (2001), implying even at the turn of the millennium that rents may increase in parity with private renting across London.

CONCLUSION — LOOKING TO THE FUTURE

The term “precariat”, derived from Pierre Bourdieu’s theories on precarity, as a way of thinking of inequality away from traditional class structures, is developing as discussion point amongst economists and sociologists.

“Precarity is built into neoliberal capitalism, in which growth is predicated on financial risk and indebtedness, in which labour markets are weakened and social protections rolled back, in which states construct barriers to deprive certain groups of workers of citizenship norms, and in which the drive for new zones of accumulation results in land enclosures, dispossession, and urbanisation without employment.” (Seymour, 2011)

Borne from entrenched neoliberal politics, the precariat is a worker of itinerant and non-fixed labour derived from the precarious late service economy we are currently in, though precarity does not solely come from the labour market but from all parts of our neoliberal society — political agency, access to housing, reduced access to social functions and services. As Seymour goes on to say, the precariat is not a “incipient class” but it is “all of us”:

“Every one of us who is not a member of the CBI, not a financial capitalist, not a government minister or senior civil servant, not a top cop or guest at a Murdoch dinner party, not a judge or news broadcaster — not a member, in other words, of the ‘power bloc’, the capitalist class in its fractions, and the penumbra of bourgeois academics and professionals that surrounds it. We are all the precariat. And if we are dangerous, it is because we are about the shatter the illusory security of our rulers.” (Seymour, 2011)

In 2018 we see the same ingredients — lack of affordable housing, lack of social agency, low wages, increased inequality — which led to the London riots of the 1980s and 2011 as well as the 1968 Paris troubles. While Harvey suggests that the 2011 rioters “mimic on the streets of London what corporate capital is doing to Planet Earth and only “what everyone else is doing in a different way” (2008), Guy Standing, an economist who has popularised the precariat term, has suggested that the private Garden Bridge may be the trigger for “a huge public revolt”. 2017 was the 800th anniversary of the Charter of the Forests which wrote into our law the common rights of citizenship and the commons and he suggested an impending protest could take place on the Thames where the symbolic Garden Bridge would have been:

“your own national river, and they’re privatising it for profit. And there [will be] huge demonstrations, huge marches, huge protests” (Standing, 2016)

This brings the whole centre of a possible cultural and social battle down, once again, onto the CSCB site and in the shadow of the two (currently stalled) projects of the Doon Street Tower and the Garden Bridge. There may be little difference between the precariat of today and the casual labour of Marx’s time, but following the reduction of union power and the pulling apart of urban democratic engagement, not least through partnerships, the main difference is the lack of consciousness, organisation and if individuals understand themselves as part of a stronger union to affect change (German and Rees, 2012, loc. 5780).

CSCB were formed to do just this against the emergent neoliberal politics, and they were successful. But over three decades later they appear to have been subsumed into the wider political landscape and are no longer the reactionary force needed for those they claim to represent. Instead, that solidarity is emerging from the CSCB tenants and other local community, as represented by TCOS in their fight against the Garden Bridge.

In interview the Coin Street resident spoke about “serious problems” over the last few years, and the question is if there is social upheaval and an uprising as Standing and others predict is to come, will CSCB support the “ordinary people” as they did in the 1980s or will they side with “those with money and power” within their partnerships?

“London has always been at its worst when those with power and money have a free reign, and always at its best when the ordinary people assert their rights against the rich and powerful. This generation is beginning to fight for those rights” (German and Rees, 2012, loc. 5780)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Awan, N., Schneider, T. and Till, J. (1989) Spatial agencies, other ways of doing architecture. Abingdon: Routledge

Bacon, G., Shah, N., Cleverly, J, Dismore, A. and Duvall. L. (2016). Business Improvement Districts, The role of BIDs in London’s regeneration. London: Greater London Authoritty. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/final_bids_report_0.pdf (Accessed: 06 January 2016)

BBC (1998) UK Diana Memorial Garden Backed by Committee. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/119065.stm (Accessed: 20 November 2016).

Ball, M. and Tuckett, I. (2007) ‘Does Coin Street’s tower compromise its principles?’, Building Design, 29 August. Available at: http://www.bdonline.co.uk/does-coin-streets-tower-compromise-its-principles?/3094148.article (Accessed: 21 December 2016).

Banham, R. (1977) ‘The Pompidou Centre, the Pompidolium’, The Architectural Review May. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/1977-may-the-pompidou-centre-the-pompodolium/8627187.article Accessed: 31 December 2016).

Berkeley Group PLC (2016) 190 Strand, London WC2. Available at: https://www.berkeleygroup.co.uk/new-homes/london/westminster/190-strand (Accessed: 17 January 2017)

Bibby, A. (no date) Coin Street — Case Study. Available at: http://www.andrewbibby.com/socialenterprise/coin-street.html (Accessed: 20 December 2016).

Brindley, T., Rydin, Y. and Stoker, G. (1989) Remaking Planning. London: Unwin Hyman Ltd.

Carmona, M. and Wunderlich, F. M. (2013) Capital Spaces: The Multiple Complex Public Spaces of a Global City. London: Routledge.

Coin Street Community Builders (2016) Working together. Available at: http://coinstreet.org/who-we-are/partnerships/working-together-2/ (Accessed: 27 December 2016).

Coin Street Community Builders (2016b) [Twitter] 28 December 2016. Available at: https://twitter.com/CoinStreet/status/814087317702856704 (Accessed 06 January 2017).

Coin Street Community Builders (2016c) The Garden Bridge, FAQs from Coin Street Community Builders (CSCB). Available at: http://coinstreet.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2016-04-04-Garden-Bridge-CSCB-FAQs2.pdf (Accessed: 06 January 2016).

Coin Street Community Builders (2016d) The Campaign. Available at: http://coinstreet.org/who-we-are/history-background/the-campaign/ (Accessed: 15 January 2017)

Coin Street Resident (2016) Interview between CSCB resident (name withheld) and Will Jennings, 15 December 2016.

Colquhoun, A. (1985) Essays in Architectural Criticism: Modern Architecture and Historical Change, Cambridge, and London: The MIT Press.

Cooper, K. (2016) Rogers urges RIBA to rethink Garden Bridge stance, The Architects’ Journal, 21 March 2016. Available at: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/rogers-urges-riba-to-rethink-garden-bridge-stance/10004397.article (Accessed 7 January 2017)

Coupland, A. (1997) Reclaiming the city, mixed use development. Edited by Andy Coupland. London: Chapman & Hall.

Cross River Partnership (2016) Our Partners. Accessible at: http://crossriverpartnership.org/partners (Accessed: 20 December 2016)

Dare Hall, Z. (2014) London’s Strand seeks South Bank success as the new ‘Northbank’. The Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/98bd987a-ba83-11e3-b391-00144feabdc0 (Accessed: 07 January 2017)

Davidson, M. (2007) ‘Gentrification as a Global Habitat: A Process of Class Formation of Corporate Creation’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 32, №4, October, p. 490–506

Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions. 2000. Our towns and cities: the future, delivering an urban renaissance. Available at: https://www.cambridge.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/rd-hq-060.pdf (Accessed: 29 December 2016)

deRoo, R. (2006). The Museum Establishment and Contemporary Art, the Politics of Artistic Display in France after 1968, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Durston, N. (2015). London Assembly Regeneration Committee’s Investigation into Business Improvement Districts. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/collated_submissions.pdf, p. 20–23 (Accessed: 06 January 2017)

Edwards, M. (2016). ‘The Housing Crisis and London’, City, Vol. 20, №2, p. 222–237.

Edwards, M. (2010) ‘King’s Cross: renaissance for whom?’, in John Punter (ed.) Urban Design, Urban Renaissance and British Cities (2010), London: Routledge. P. 189–205.

German, L. & Rees, J. (2012) A People’s History of London. London and New York: Verso.

Glancey, J. (2002) ‘Heart of gold’, The Guardian 8 April. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/arts/critic/feature/0,1169,686501,00.html (Accessed: 29 December 2016).

Graham, S. (2016) Vertical. London & New York: Verso.

Greater London Authority (2015) Regeneration

Committee, 13 October 2015, Transcript of Agenda Item 6, Business Improvement Districts. London: Greater London Assembly. Accessible at: https://www.london.gov.uk/moderngov/documents/b13659/Minutes%20-%20Appendix%201%20-%20Transcript%20-%20BIDs%20Tuesday%2013-Oct-2015%2010.00%20Regeneration%20Committee.pdf?T=9 (Accessed 06 January 2016)

Hatherley, O. (2013) ‘Richard Rogers at 80: principles and power’, The Guardian 20 July. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/jul/20/richard-rogers-architecture-80-royal-academy (Accessed: 21 December 2016).

Hatherley, O. (2014) ‘Richard Rogers (1933-)’, The Architectural Review, 29 August. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/archive/reputations/richard-rogers-1933-/8668832.article (Accessed: 20 December 2016).

Harvey, D. (2008) ‘The Right to the City’, New Left Review, 53, September-October. Available at: https://newleftreview.org/II/53/david-harvey-the-right-to-the-city (Accessed: 31 December 2016).

Heatherwick Studio (2016) Garden Bridge. Available at: http://www.heatherwick.com/garden-bridge/ (Accessed: 17 January 2017)

Harvey, D. (2012) Rebel Cities. London & New York: Verso.

Hopkirk, E (2014) Richard Rogers backs Heatherwick’s garden bridge, Building Design, 8 September. Available at: http://www.bdonline.co.uk/richard-rogers-backs-heatherwicks-garden-bridge/5070725.article (Accessed 7 January 2017)

Hurst, W. (2016) ‘Lumley reveals Garden Bridge land permission is in doubt’, The Architects’ Journal, 21 September 2016. Available at: https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/lumley-reveals-garden-bridge-land-permission-is-in-doubt/10011994.article (Accessed: 06 December 2016).

Ipsos Mori (2009). Residents, Employees and Visitors in the South Bank neighbourhood

Autumn ― Winter 2008/09 Final report, London: Ipsos Mori. Available at: www.sbeg.co.uk/page/3114/MORI-Survey-Exec-Summary (Accessed: 31 December 2016)

Jacobs, M. (1988). ‘Margaret Thatcher and the Inner Cities’, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 23, №38, p. 1942–1944.

Jeffrey, N. (1997). ‘Coin street yields a high return’, New Statesman, 20 June, p. 32–35.

Jennings, W (2016) Issues. Available at: http://abridgetoofar.co.uk/issues/ (Accessed 06 January 2016).

Johnson, D (2015) A land value tax should pay for London’s new Garden Bridge. Available at: http://www.citymetric.com/politics/land-value-tax-should-pay-londons-new-garden-bridge-621 (Accessed: 7 January 2017)

King, L. (2017) Email to Will Jennings from Louise King, Director of Communication & Information at CSCB, 6 January.

Kufner, J. (2011) Tall building policy making and implementation in central London: Visual impacts on regionally protected views from 2000 to 2008. PhD thesis. Department of Sociology, Cities Programme of the LSE.

Laing, R. and Novy, A. (2014) Cooperative Housing and Social Cohesion: The Role of Linking Social Capital. European Planning Studies, 22(8), p. 1744–1764.

Law, C.K, Wong, Y.C. Ho, L., Yu, R. and Lee,(8), p. V. (2009). Case Study Report: Regeneration of the South Bank, London, Hong Kong: Urban Renewal Strategy Review. Available at: http://www.ursreview.gov.hk/eng/doc/SC%20paper%2021-2009_merged_Eng.pdf (Accessed: 2 December 2016)

Livingstone, K. (2004) The London Plan. London: Greater London Assembly.

Livingstone, K. (2016) Being Red, A Politics for the Future. London: Pluto.

London SE1 (2016) Sky becomes latest corporate backer of Garden Bridge, London SE1, 13 January. Available at: http://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/view/8594 (Accessed: 17 January 2017)

London SE1 (2016) South Bank councillors challenge ‘unsound’ Garden Bridge decision, London SE1, 17 April. Available at: http://www.london-se1.co.uk/news/view/8745 (Accessed: 17 January 2017)

Lumley, J. (2005) No Room for Secrets, London: Penguin.

Moore, R. (2016) Slow Burn City, London: Picador.

Mount, H. (2014) ‘The big divide: North v Southbank’, The Evening Standard, 1 May 2014. Available at: http://www.standard.co.uk/lifestyle/esmagazine/the-big-divide-north-v-southbank-9306746.html (Accessed: 06 December 2016).

Murphy, D. (2012) The Architecture of Failure, Alresford: Zero Books.

Nixon, M., Potts, A., Fer, B,, Hudek, A. and Stallabrass, J. (2001) Round Table: Tate Modern, October, Vol. 98, Autumn, p. 3–25

Northbank BID (2016) The Board. Accessible at: https://thenorthbank.london/the-northbank-bid/the-board/ (Accessed: 20 December 2016)

Payne, A. H., (1846) ‘Payne’s Illustrated Plan of London’. Available at: http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/crace/p/007000000000007u00252000.html (Accessed: 26 December 2016)

Raco, M., Street, E. and Trigo, S. F. (2013) ‘Privatising Democracy? The Transformation of Local State-Market Relations in Urban Governance’, ICPP 213–1st International Conference on Public Policy. Available at: http://www.icpublicpolicy.org/IMG/pdf/panel_39_session1_raco_street.pdf (Accessed: 22 December 2016)

Rogers Stirk Harbours (no date-a) NEO Bankside. Available at: http://www.rsh-p.com/projects/riverlight/ (Accessed: 27 December 2016).

Rogers Stirk Harbours (no date-b) Riverlight. Available at: http://www.rsh-p.com/projects/riverlight/ (Accessed: 27 December 2016).

Rogers Stirk Harbours (no date-c) Centre Pompidou. Available at: http://www.rsh-p.com/projects/centre-pompidou/ (Accessed: 30 December 2016).

Rogers Stirk Harbours (no date-d) Lloyd’s of London. Available at: http://www.rsh-p.com/projects/lloyds-of-london/ (Accessed: 30 December 2016).

Rogers Stirk Harbours (no date-e) Coin Street. Available at: http://www.rsh-p.com/projects/coin-street/ (Accessed: 30 December 2016).

Rogers,R. (2013) ‘The Pompidou captured the revolutionary spirit of 1968’. Interview with Name of Interviewee. Interview by Marcus Fairs for Dezeen, 23 July. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2013/07/26/richard-rogers-centre-pompidou-revolution-1968/ (Accessed: 30 December)

Rogers, R. (1982) Lloyds to Coin Street [Lecture], Module code: module title. The Architecture Association. 12 January. Available at: http://www.aaschool.ac.uk/VIDEO/lecture.php?ID=795 (Accessed: 5 June 2016).

Rogers, R. (2015) The garden bridge will be an oasis of calm and beauty in the heart of London, The Guardian, 7 June. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/07/garden-bridge-oasis-of-beauty-richard-rogers (Accessed: 7 January 2017)

Seymour, R. (2012) We Are All Precarious — On the Concept of the ‘Precariat’ and its Misuses. Available at: http://www.newleftproject.org/index.php/site/article_comments/we_are_all_precarious_on_the_concept_of_the_precariat_and_its_misuses (Accessed 7 January 2017)

Smith, N. (1979) Toward a Theory of Gentrification A Back to the City Movement by Capital, not People, Journal of the American Planning Association, October 1979, p, 538–548

Spencer, D. (2015) The Architecture of Neoliberalism. London: Bloomsbury Academic

Stephenson, B. (2015). Response to the London Assembly Regeneration Committee’s investigation into Business Improvement Districts. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/collated_submissions.pdf, p. 35–38 (Accessed: 06 January 2017)

Spurr, S. (2015) Tallest Towers Proposed in Lambeth, Estates Gazette, 30 October. Available at: http://www.estatesgazette.com/blogs/london-residential-research/2015/10/tallest-proposed-skyscrapers-lambeth/ (Accessed: 15 January 2017)

Standing, G. (2016) Changing Utopia — or what Guy Standing learned from the Lady of the Future [lexture]. Octoberdans 2016, 25 October. Available at: https://vimeo.com/191790608 (Accessed 17 December 2016)

Stewart, G. (2013) Bang! A History of Britain in the 1980s. London: Atlantic Books.

Street, E. (2011) (Re)shaping the South Bank: The (post) politics of sustainable place-making. PhD thesis. Kings College London

Taylor, D. (1996) Summary of ‘The Potential of the Thames: A New Heart For London’, The Architects’ Journal, 22 February. Available at: http://www.architecturefoundation.org.uk/assets/files/Exhibition%20Resources/AS961_LIT21C__AJSummary%202.pdf (Accessed: 10 January 2017)

Thames Central Open Spaces (2016) The Campaign Against the Garden Bridge. Available at: http://www.tcos.org.uk/the-campaign (Accessed: 06 January 2017)

Thames Central Open Spaces (2016b) Untitled post [Facebook] 17 June 2016. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/TCOSLondon/photos/a.899930520038507.1073741828.898709250160634/1189432194421670 (Accessed 7 January 2016)

Towers, G. (1998) Re-forming multi-storey housing, the regeneration of urban housing estates in Britain. PhD thesis. University of Luton.

Tuckett, I. (1988) Coin Street: There is Another Way, Community Development Journal, Volume 23, Issue 4, p, 249–257

Tuckett, I. (2001) What Next for Coin Street? [lecture]. The Design for Homes Intensive Flair Conference. June. Available at: http://www.designforhomes.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/CoinStreet.pdf (Accessed: 15 November 2016).

Urban Task Force (2005) Towards a strong urban renaissance. Available at: http://www.integreatplus.com/sites/default/files/towards_a_strong_urban_renaissance.pdf (Accessed: 29 December 2016)

Urban Task Force (1999) Towards an urban renaissance, executive summary. Available at: http://dclg.ptfs-europe.com/AWData/Library1/Departmental%20Publications/Department%20of%20the%20Environment,%20Transport%20and%20the%20Regions/1999/Towards%20an%20Urban%20Renaissance.pdf (Accessed: 29 December 2016)

Walker, P. (2016) ‘ London’s garden bridge: will ‘tiara on the head of fabulous city’ ever be built?’, The Guardian, 3 January. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jan/03/london-garden-bridge-will-tiara-on-head-fabulous-city-ever-be-built (Accessed: 6 January 2017).

Wallis, J., (1797) ‘Wallis’s Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster 1797'. Available at: http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/crace/w/007000000000005u00180000.html (Accessed: 26 December 2016)

Watts, J (2014) City Hall says yes to Garden Bridge… but they need to find £65m before work can start. The Evening Standard, 19 December 2014. Available at: http://www.standard.co.uk/news/london/garden-bridge-city-hall-green-light-approval-mayor-of-london-river-thames-river-crossing-9934945.html (Accessed 7 January 2016)

Worsley, G. (2002) ‘Nothing but a Pipe Dream’, The Telegraph 26 January. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/art/3572303/Nothing-but-a-pipe-dream.html (Accessed: 30 December 2016).