Learning from Los Santos: Computer games & their effect on our reading of space

Essay2018

INTRODUCTION

This essay will consider the relationship between gamespace and physical space, questioning if the sense of individual freedom and agency in open-world computer games can affect our sense of rights to the city. Following a “personal ethnography” introducing my first encounter with a video game centred on urban constructs, SimCity, Chapter 1 The Real City: First Space will introduce some of the topics related to the rights of the city and urban agency. These include the relationship of the city and ways of engaging with it by writers and groups including the Situationists, Henry Lefebvre, Jean Baudrillard, Kevin Lynch and Rayner Banham which will recur throughout.

Chapter 2 The Virtual City: Second Space will then consider spaces offered up by video games, initially considering the “god-like” top-down view of SimCity before exploring the movement towards first-person experiential notions of physical space as exemplified by the Grand Theft Auto series. The limitations of considering such renderings of place will be considered before the actual landscapes created and experienced will be referenced using terms and ways of reading the city introduced in Chapter 1, but now through a digital lens.

Chapter 3 Return to the Real: Third Space will see us exit the virtual realm and return to the physical, now bringing some of the ideas and ways of reading space developed in Chapter 2 into our more familiar lived experience. Possibilities of what it means for experiences of simulated space to slip into our reading of the real world will be explored and it will be asked whether this can provoke ideas of reclaiming the city as witnessed in activities including urban exploration.

This essay understands that there are limitations to considering the complex, vast and deeply personal interactions experienced in the physical realm with those of a comparatively tiny, controlled and constructed digital open-world and these will be raised. However, the technology of this new kind of space is very much in its infancy and it is worth considering these small shifts in behaviour at an early stage as our digital and real lives become further entangled and technology develops at pace.

Lastly, a word on the three-chapter structure of this paper. Charting the Ludodrome, The Mediation of Urban and Simulated Space and Rise of the Flâneur Electronique (Atkinson & Willis, 2007) includes the following diagram and ways in which the inhabitant of real and simulated space carries ideas, ways of being and experiences from one to the other.

(Image from Atkinson & Willis, 2007)

(Image from Atkinson & Willis, 2007)

The section structure follows this movement from the real to the virtual and back again using the notions of importing, segue and slip to relate each space to the previous. This will be will be framed around Edward Soja’s concepts of first, second and third space (1996, p. 10), where first spaces are “those which can be empirically mapped”, second spaces Spaces are “thoughtful representations of human spatiality in cognitive forms” and third spaces parallel Lefebvre’s idea of lived space, or for Soja, “real-and-imagined”, or “realimagined”, spaces.

Notes: The primary computer games primarily referred to in this paper Grand Theft Auto is from a long-running series dating from 2001. When not explicitly stated the reader should assume I am referring to the latest versions from each series even when referring to commentary which was written in relation to earlier releases. For instance, many papers regarding Grand Theft Auto, it’s open-world, simulated urban space and issues within, were written in response to 2004’s Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas and not the most recent edition, 2013’s Grand Theft Auto V. The reader should assume I am of the opinion that the commentary within also stands for the most recent edition and, if anything will be furthered through the massively increased scope and scale of Grand Theft Auto V from earlier releases. Grand Theft Auto V is abbreviated to GTAV throughout this paper.

A PERSONAL ETHNOGRAPHY

The ten-year old me and an Italian exchange student whose house I had arrived at the night before didn’t have a huge amount in common. I recall the awkwardness of children trying to understand and get to know a stranger compounded by a lack a shared language. Kicking a football and stuttering ‘conversations’ formed our main attempts at connection. Small trips out of Rovato, the small Lombardy town I had been transplanted to, were arranged for us visiting English students. I recall the immaculately preserved Roman amphitheatre in Verona, the vertiginous cathedral in Milan and labyrinthine Venetian canals, cities like I’d never seen before.

But my host and I bonded over urban spaces and architectures quite distant to the classical antiquity of northern Italy, instead we found a mutual language and interest in post-industrial North American cityscapes. On his family computer, he had a copy of the game SimCity (1989) and an inordinate amount of the week’s visit was spent in this game as we acted as god-like creators of cities, arguing in mixed tongues over where the power plant should be located, where the bridge over the river should be located, whether we should construct new houses around the historic forest or bulldoze our way through centre of it. Despite different upbringings, he and I could mutually understand the impact that our new airport would have on the residential zones, we found a way to plot the route for the new railway line into the city centre, even if it did require destruction of a successful shopping street. It was my first experience of a computer game which engaged with ideas of the city and wedged itself firmly into my psyche which was developing an interest in built places and ideas of one day becoming an architect.

Those formative experiments with virtual place-making still resonate, as they do for many of my generation who now have an interest or work in architecture and planning — I am not the only one who found a cocktail of SimCity and Lego to be the gateway drug to a lifetime of architectural curiosity. But nearly thirty years on a lot has changed, computers have developed in power and processing capability vastly, the games we experience now have a deeper relationship and mirroring of reality, games themselves have now become mass-entertainment and, personally, my reading of cities, architecture and our relationships to them has somewhat evolved.

1 - THE REAL CITY: FIRST SPACE

“To be lifted to the summit of the World Trade Centre is to be lifted out of the city’s grasp. One’s body is no longer clasped by the streets that turn it and return it to an anonymous law… His elevation transfigures him into a voyeur. It puts him at a distance. It transforms the bewitching world by which one was “possessed” into a text that lies before one’s eyes. It allows one to read it, to be a solar Eye, looking down like a god… the fiction of knowledge is related to this lust to be a viewpoint and nothing more.” de Certeau, M. (2007, p.92)

Michel de Certeau compares the top-down vantage of New York’s grid viewed from the top of the former World Trade Centre with how mapping and considering the city from an all-encompassing distance and detachment. The vantage of governments, planners and authority. The top-down view allows the city to be read as a text of history, geography, class and culture in a way not dissimilar to how my 10-year-old mind imagined a depth of meaning and narrative into the digital constructions in SimCity. While to our modern eye the graphics, algorithms and mechanisms of the game appear naive compared to the photo-realism and vast computational possibilities that computers can now offer. But it offered a new way of considering the real and as a window into a new way of experimenting with place for the millions who played what became one of the best-selling games ever (Rivenburg, 1992). This god-like vantage was only a simulation, but it offered a way of reading and experimenting with cities in such a way that the designer hoped users would “suspend their disbelief” (ibid.).

To de Certeau the top-down vantage experienced from the World Trade Centre only offers a “representation” or “simulacrum” of a city as a “transparent text” (2007, p.92). He suggests this way of considering city is useful only to an urbanist, planner or cartographer while the “ordinary practitioners” of the city are the walkers and inhabitants at street level “whose bodies follow the thicks and thins of an urban text they write without being able to see it” (ibid.). His writing explores the tactics by which individuals, often unwittingly, act against the structures of control and society using a top-down vantage to repress those below.

By referring the walker, de Certeau was invoking key ideas in writing on the city; the flâneur and the dérive. The character of the flaneur, a city wanderer who aimlessly strolled, observing urban happenings around them, was articulated by Walter Benjamin who considered him1 as a kind of investigator of the city, piecing together clues of an unravelling, open-ended narrative. The flâneur was a creature of capitalism, navigating Parisian arcades amongst people going about their business, observing multitude of objects for sale, psychologically montaging fleeting moments. Benjamin’s flâneur had an outsider’s gaze of observing and critiquing not dissimilar to de Certeau’s but without the distancing of verticality.

If the city is a text these offer two methods for reading it: de Certeau’s top down, all-encompassing totality in which we can scan between areas observing disjuncts between regions, understanding scope of geography and structural systems arranged throughout; and Benjamin’s street-level montage with a fixed singular viewpoint but an eye free to wander as much as the feet, forming something akin to hypertext of linking strands and ideas (Featherstone, 1998).

(Image from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/zemlinki/3418067412/)

(Image from: https://www.flickr.com/photos/zemlinki/3418067412/)

There is a linearity from the flâneur to the idea of the dérive, a method of play in the city developed by the Situationists International as a device to challenge the orthodoxy of control in an increasingly consumerist society. Outlined by Guy Debord in Theory of the Dérive (1956) it differentiates from flâneurism by operating with a “playful-constructive” method of prescribing behaviour and/or route through the streets with a desire to test one’s sense of agency or choice, to “study terrain” or “emotionally disorientate” in a psychogeographical sense.

The relationships between the self and the city/state, as tested with dérive exercises, was further developed by Henry Lefebvre in his 1968 Right to the City (1996). He questioned the objective reading of the city as text, stating “aspect of mediation” cannot be forgotten, emphasising that it cannot be considered as a singular, completed text while personal structures, ideas and forms are projected onto the city (1996, p.102).

The right to the city has become increasingly contested and the changes within world cities such as London, Los Angeles and New York since 1968 have had a vast impact upon the urban experience for all users of the city through increasing neoliberal attitudes to the role of the city, rapid growth in free-market, speculative development, increased surveillance and cost of living. Lefebvre’s writing is now a key grounding for critical thought on the future of the city as it represents “nothing less than a revolutionary conception of citizenship” (Merrifield, 2017, Loc.123).

This increasingly segregated, partitioned and surveilled urban space is impressing onto citizens the top-down, planned and controlled mechanisms de Certeau described (Graham, 2009). The city of the walker is being reconstructed into that of the consumer. Restrictions upon the lived experience of the city, control mechanisms implemented upon citizens and the militarisation of civil space indicates a strong rendering of the city as First Space, defined by Edward Soja as “fixed mainly on the concrete materiality of spatial forms, on things that can be empirically mapped” (1996, p.10). First Space is focused on the material world and physicality of space so the city becomes place of channelling and control mechanisms reducing the psychogeographical potential for the walker.

2 - THE VIRTUAL CITY: SECOND SPACE

“For a European [Los Angeles] is appalling and unliveable. You can’t get around without a car and you pay exorbitant sums to park it. And yet at the same time, it is unbelievably fascinating. What fascinates and disgusts me are the streets of luxury shops with superb windows but which you can’t enter into… These streets are empty.” Lefebvre (1996, p.208)

Walter Benjamin never made it to L.A.. Other members of the Frankfurt School fled the anti-semitic rise of Nazism and settled in exile in Santa Monica, but in 1940 Benjamin committed suicide in Catalonia fearing Spanish police would deport him back to Germany. If he had made it to the American west coast, as Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer did, one can only wonder where his ideas of urban writing would have taken him within this sprawl of imagery, signs, vehicles and privatisation.

Lefebvre’s comments, above, on Los Angeles were made alongside a statement that neoliberalism would lead to “a space abandoned to speculation and the car” instead of nurturing a city to become “a place where different groups can meet… be in conflict but also form alliances” (1996, p.207). L.A. is a city observed through car windows by drivers and passengers. Jean Baudrillard wrote, “All around, the tinted glass façades … frosted surfaces. It is as if there were no one inside the buildings. This is what the ideal city is like.” (1986)

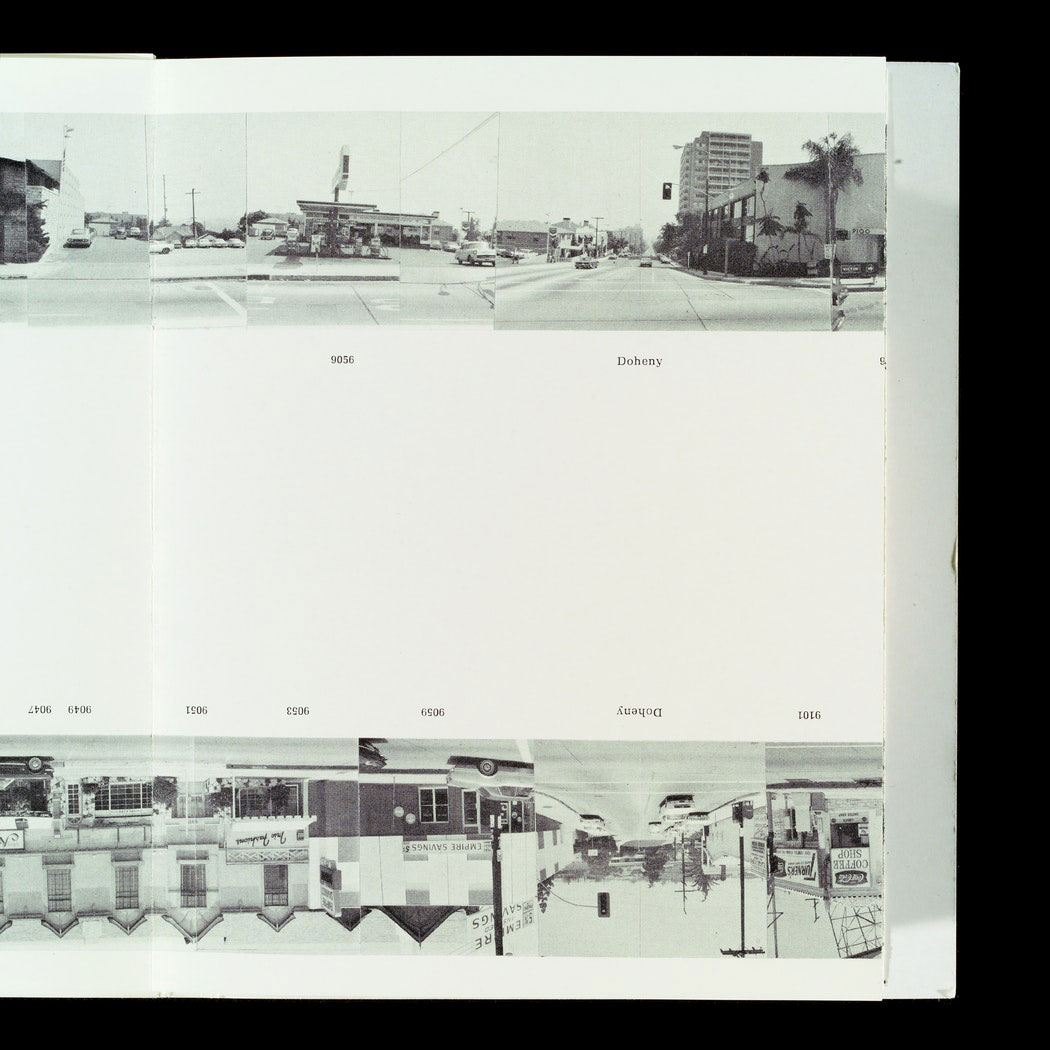

“Can cruising in a car, or being stuck in a traffic-jam in Los Angeles… be regarded as a form of flânerie?” asks Featherstone (1998), perhaps also contemplating Benjamin’s unwritten books. As Baudrillard observed of America, “the point is to drive because that way you learn more about society than all academia could ever tell you” (2010, p.56) and views through the windscreen have been central to modern American art: psychological questioning of place in Jack Kerouac’s On The Road (Dominguez, 2004); Ed Ruscha’s shopfront photographs from a car window in Every Building on the Sunset Strip (1966); modern films like Drive (Winding Refn. 2011) with lengthy scenes racing through L.A., the protagonist at once embedded in and psychologically distant from a city of reflective glass and stucco surfaces (Hawthorne, 2011). Artist Thom Anderson’s voice-over in documentary Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) reads, “traditional public space has been largely occupied by the quasi-private space of moving vehicles”. Benjamin may have been viewing the post-war city through a windscreen.

On a recent holiday to L.A. I had a recurring uncanny sense of having previously visited. Perhaps because the city has been represented so many times in film that the feel of the place, if not architectural detail, feels familiar, author Donald Waldie writing “we are all citizens of Los Angeles because we have seen so many movies” (2007). The city isn’t always itself, it repeatedly acts as a stand-in for other places, Anderson’s filmic study (2003) on the real and unreal city giving examples of places in the city representing Switzerland, China, or any city in the world, real or imaginary, in film and the variable architectural and geographical spaces in and around L.A. are a reason the film industry rooted itself in the area.

But for a place’s history to be built on (mis)representation and scenography also results in a flattening and folding of history evidenced by ongoing archaeological digs in dunes near L.A. uncovering “Egyptian” remains from Cecil B. DeMille’s 1923 set for The Ten Commandments (Katz, 2017), buried to avoid appropriation by another director. Barthes, quoting Kafka, suggests “we photograph things to drive them from our minds” (1981, p.53) and as the most photographed city on earth L.A. exists in the imagination. Architectural writer, Rayner Banham taught himself to drive to the city “in the original”, comparing it to earlier generations who learnt Italian to read Dante in the original (1971, p.5). But what is the original in a place which buries its façade of history?

One barely fictionalised rendering of the city is the setting for computer game Grand Theft Auto V. Los Santos is a scaled-down version of L.A., its architecture and surrounding landscape offering players a vast territory to explore, the gamespace acting as a “temporary envelope of urban reality” (Atkinson & Willis, 2007). It is an open-world game, in which there are missions the player can engage with at their leisure but are equally free to explore simulated territories without purpose other than exploration.

Open-world has been a mechanism within game-making of interest to designers from the first days of programming, though limitations of early technology meant gamespaces were usually text-based with a strong reliance upon the player’s imagination. Open-world took a huge leap forward in 1984 with the release of Elite in which players operated a first-person controlled spaceship trading goods across a galaxy of hundreds of planets[2]. Players could progress through the game not just by engaging in capitalist interplanetary trading missions, but also through piracy or illegal slave and drug trafficking. The designer Dave Braben not just simulating safe behaviours but also that which is deeply illegal, “we wanted the player to have freedom to do good and to do bad” (Camborn et al., 2013, 24mins).

(Image from: https://gamedevelopment.tutsplus.com/articles/using-texture-atlas-in-order-to-optimize-your-game--cms-26783)

(Image from: https://gamedevelopment.tutsplus.com/articles/using-texture-atlas-in-order-to-optimize-your-game--cms-26783)

The next leap-forward in free-choice gaming was Simcity, a sandbox game without prescribed route within the ludic space. Acting as mayor and god-like city designer, the player is presented with an empty landscape into which they lay roads, designate usage-zones and prescribe political and financial regulations. As a 10-year-old on Italian exchange I was incredibly excited by the apparent openness to imbue within the game one’s own narratives and ideas, rather than passively receiving an unfolding story as per most games or other media such as literature and cinema (Poremba, 2006).

There were no endpoint or missions within the game, just free-experiment in place-making, though with all gamespaces there were boundaries to free action. Throughout the SimCity series these limits have not just been due to technical requirements of computers, but also in-built limits as to what kind of cities are possible to design. Hardwired into the game mechanics are notions of “good” and “bad” reflecting US-centric notion of city success modelled on growth and capitalism. Some of these, including planning models, transport and heritage are discussed by Bereitschaft (2015), noting that poor areas are simply demolished and rebuilt as city inhabitants get richer due to “good” decisions by the game-player. There is no physical displacement and “gentrification… may be construed by the player as a simplistic and benign process, a sentiment not far removed from prevailing neoliberal ideology.”2

SimCity utilised de Certeau’s top-down god-like vantage, but since 1989 computer technology, processor power, graphics capabilities and, not least, audience numbers and their demands of gamespace, has increased vastly resulting in later versions developing incrementally more complex, layered and graphically involving worlds. It also resulted in a slowly shifting vantage upon the created cities with each iteration of the game allowing players to zoom closer and closer to the minute details of the urban environment and activities within. The most recent version, SimCity 5 (2013) allows the player to zoom right in and fly around their city in 3D, clicking on individual inhabitants to see where they work and how they navigate the created place.3

(Image from: https://edition.cnn.com/2013/03/01/tech/social-media/apparently-this-matters-new-simcity/index.html)

(Image from: https://edition.cnn.com/2013/03/01/tech/social-media/apparently-this-matters-new-simcity/index.html)

This shift in vantage has also occurred in the Grand Theft Auto series. starting in 1997 with a top-down structure in which the player controls a group of criminals navigating a rudimentary mapping, even considered graphically rudimentary at the time (IGN, 1998). As the series developed so has the scale and vantage of the world in which play occurs, through to the most recent release GTAV in which characters have a vast simulated canvas loosely based on Los Angeles, alternating between three protagonists in over-the-shoulder third person control.

The offer to the player’s free-will within the open-world also greatly increased as the series progressed. While there is condemnation of the game in popular media due to the lawlessness and potential violence, as Braben stated the player chooses these decisions and could just as equally traverse the landscape in a totally lawful way. In GTAV, if a player wished they could stop at every traffic light, watch a stand-up comedy show, cruise the city listening to radio stations, play darts, tennis or golf, go jet skiing, hang-gliding or go for an off-road bicycle ride into the mountains for sunset (Petit, 2013). In short, it is possible to play the game by simply existing as an flâneur electronique, simply exploring the city and surrounding landscape, climbing buildings, freely discovering place and absorbing the montage of urban sounds and images (Atkinson. & Willis, 2007; Whalen, 2006).

Consequently, the GTA series has had a huge impact upon contemporary culture. In 2002 the designers were shortlisted for London’s Design Museum’s Designer of the Year award (BBC, 2003), losing to Jonny Ive and the iMac, while Time Magazine called GTAV “Today’s Great Expectations” (Gillespie, N., 2013). The aesthetic of the game has now also come to influence film design, critic Keith Stewart suggesting the film Drive is essentially “a non-interactive version of Grand Theft Auto” (Camborn et al., 2013, 1hr8mins). With hundreds of millions of active Los Santos flâneurs it is not only mass-culture but can have an impact with how we read and engage with the built environment, players effectively writing a new script of place with every play (Tavinor, 2011; Bernstein, 2013).

The design team of GTAV spent months ethnographically researching Los Angeles and meeting with different inhabitants (Hill, 2013) and taking over 250,000 photographs (Bernstein, 2013) before a team of 1,000 people developed the game over three years. They modelled “an extremely realistic version of Los Angeles that doesn’t exist” (Sweet, 2013), akin to a tourist destination or folklore museum (Miller, 2008). The resulting Los Santos is a scaled-down version of L.A. re-mapping select areas of the city to be read as a Situationist fragment collage, akin to Guy Debord’s Naked City (McDonough, 2002, p.241), using ideas of the dérive and utilising simulated landmarks not only as mediators between simulated space and the real L.A. but also as navigational devices as outlined in Kevin Lynch’s 1960 Image of the City (Tea, 2005). Lynch described the highways of L.A. as offering a sense of urban play for the adult user, and so it is the case in GTAV that non-mission freely driving around the city, exploring, offers as much sense of play for many users as missions within (Bogost & Klainbaum, 2006).

(Image from: https://www.gamestar.de/artikel/gta-5-mehr-als-1000-modifikationen-fuer-autos-und-motorraeder,3025511.html)

Because of the scale, and that it is set in car-city L.A., most navigation takes place in vehicles using landmarks, the on-screen minimap acting as satnav (Chesher, 2012) for journeys with more play and less purpose than those of a real city. It may be because of experiences playing GTAV that when driving in L.A., with the windscreen acting as movie screen (Jacobs, 2006) in a cinema-city, that I had a sense of uncanny. Ernest Jentsch’s 1906 essay, On the Psychology of the Uncanny (1997), gave example of a reader not discerning if a created literary character is human or automaton, a hint of future simulated landscapes replicating the real.

GTAV is predominantly played in the third-person which could be thought to distance the user from the inhabited space and embodied character, though when using a tool, or driving a car, we psychologically treat the tool as an extension of self in which the tool is subsumed into our mental representation of body and its capabilities (Cardinali, 2009). Thus, when operating an avatar, however non-representational it is then it too is experienced as an extension of self, enabling us to “think through questions of agency and existence, exploring in fantasy form aspects of [our] own materiality” (Rehak, 2003). The constant flitting between one’s internal illusion of a unity of self and simultaneously existing as an extended detached self on screen is “liminal play” (Ibid.).

What is true of the embodied character is also true of the space in which it operates, so while Los Santos is clearly simulated and while we know we are holding a controller and looking at a screen, it is still an extension of self and therefore one inhabits a virtual city with the same self which inhabits the real. When one explores the simulated city of Los Santos the player is bringing into it life-experiences of other cities they have inhabited or, as Atkinson & Willis describe, “importing” (2007) the real into the virtual.

(GTA Image from: http://www.gtaaddicted.com, photograph by the author)

GTAV is designed with strong satirical takes on late-capitalism throughout the whole narrative and experienced moments of the game (Scimeca, 2013). From numerous politically left and right radio stations you can flick through (Redmond, 2005), adverts around the city (McDermot, 20130) and company names (Kophler, 2011) encountered right through to deeper plot-points of missions and characters encountered. Los Santos offers a space for exploring the society it mirrors (Murray, 2005) and if any player cannot identify the embedded critical satire within the game it may be because our real-would culture resembles it too much (Ibid.). Within the context of a gamespace, the designers offer a critique of neoliberal America, encouraging the player to consider various issues related to place, race, state, authority and agency using both scripted and subtler means (Redmond, 2006). Designed in Scotland with an outsiders’ gaze, so key to Benjamin’s observations, British humour and dry wit saturates the text (Smith, 2017).

When Guy Debord cut up a map of Paris and montaged the pieces as Naked City he created a “restructuring of a capitalist society and the very form of a critique of this society” (McDonough, 2002, p.253). If the violence in creating urban homogeneity hidden within the plan of Paris was made visible by the physical act of montage bringing them into the open (Ibid. p. 249) and the dérive was a mode of experiencing, witnessing and reading the urban situation then it is also the case that the re-mapping in GTAV can highlight social and critical issues of urbanisation using L.A. as the simulated original. The satirical critique within the gamespace aids the reveal of violence and social inequalities onto which the architecture and city is mapped.

GTAV is open-world but as with SimCity’s embedded neoliberal constructs there are limits to modes of behaviour and actions within. In a third-person simulated experience such as GTAV the player inhabits a character who not only functions as avatar-extension of self (Rehak, 2003) but who also has a scripted and embedded back-story within the gamespace. These are “encoded behaviours” (Miller, 2008) which the character possesses but differ to the gameplayer’s own life-experiences meaning the gamespace creates a performance situation rather than a totally sculptable, personable experience.

So, when entering the virtual city and surrounding landscapes of Los Santos a player abandons their personal histories, identities and even class-allegiances but are still somewhat tied to a mode of seeing, and doing, related to the character they inhabit. Despite this, they can still exist in the city as Debord characterised for the dérive, forgetting “for an undefined period of time, the motives generally admitted for action and movement… abandoning themselves to the attractions of the terrain and the encounters proper to it.” (1956, p. 50). This encountered space relates to Edward Sojas Second Space, one that is “conceived in ideas about space, in thoughtful re-presentations of human spatiality in mental or cognitive forms” (Soja, p.10), the interpreted, fragmented, satirical and reconstructed version of the real.

3 - RETURN TO THE REAL: THIRD SPACE

“It is the map that precedes the territory…it is the map that engenders the territory… Simulation threatens the difference between ‘true’ and ‘false’, between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’.” (Baudrillard, 1988, p.166)

When the player puts down the controller and turns off their screen they return to the real carrying with them residue of their virtual experience and actions within. Atkinson and Willis (2007) call this the segue, a “sustained interpretation of the real urban environment”, and slip, a “temporary interpretation of an element of real urban contexts in the language, narrative or physical constructs of the game world”.

In a modern-age where we constantly flit between real and virtual, as well as between different presentations of self in different domains, then the brief slip of the virtual memory into the physical now is increasingly common. My uncanny experiences driving in L.A. were forms of slip. I am not a heavy-gamer but even so my previous visits to Los Santos acted not only as a cyber-foreshadowing of my holiday but also led to frequent slips suggesting an uncanny deeper sense of a place I had never physically visited. Indeed, it gave me some sense of citizenship and understanding towards an urban environment vastly alien to any place I had ever experienced in the real before.

Concerns are voiced that using stereotypes (of place, race, culture, class etc.) to create algorithms, satire or simulacra as a compacted version of reality can lead to embellishing stereotypes or behaviours in the real world. This is raised by Atkinson and Willis (2007) in relation to the over-simplification of reading urban spaces and by Miller (2007) and Leonard (2006) in relation race. However, as Miller explores elsewhere (2008) it allows a player to embody a character, their backstory and personality, they would only ever previously have externally observed and considered. As such with careful scripting and a well-designed gamespace this can lead to a deeper understanding of social or cultural conditions and others’ experiences within the real world. Miller, a white woman playing as a black character, said it “was a novel way to experience a poor black urban landscape… [reshaping] my sense of public space and public safety, including my response to the sight of police” (2008).

Atkinson and Willis ask if this “sense of deep engagement with the game world could lead to a deeper sense of exhilaration with real-world spaces” (2007). Interviewees told the authors that when in the real city they missed familiar spaces of Los Santos, suggesting the physical environments they lived in offered no urban familiarity or interest. These interviews took place in Hobart and Melbourne, but issues of inhabiting an urban environment which offers no sense of belonging or citizenship is true of many cities within neoliberal political economies.

It is long known that gaming can offer learning benefits and SimCity has been used as a teaching aid exploring urban management issues throughout the series (Kim & Shin, 2016 and Nilson, 2008). There has also been much coverage, largely in mainstream media (Kleinman, 2015) and some in academic research (eg. Van Horn, 1999 and Ward, 2010) with regards to simulated violence in computer games, including GTAV, leading to real world violence. The United Nations even recently proposed computer games as powerful vehicles to “further the work of peace education and conflict resolution.” (Darvasi, 2016).

Less researched is whether open-world games, especially those set within urban spaces such as Los Santos, can lead to a different understanding of and agency towards the city. If there is acceptance that computer games can aid learning with strategic, top-down authoritative understanding of structures, logic and systems, and there is research into whether violent traits can be learnt through playing immersive simulation why is there not the same suggestion of, and research into, critical and political understanding of place and citizenship learnt from such immersive simulations?

Zeynep & Zeynep’s research into using SimCity to aid civic engagement suggested it may “encourage Turkish adolescents to demand” public spaces to be zoned into the city, lead them to “pay their taxes” and motivate teenagers to one day “take active roles in local governments of the future” (2010). It could be argued that these simply only further neoliberal participatory processes, continuing existing trajectories to public space and rights to the city, especially considering the late-capitalist US economic and political limitations built into SimCity as outlined.

Conversely, Sanford and Madill (2006) ask if gameplaying can help individuals “explore alternatives to the reality of adult society and its patriarchal, imposed rules”, testing “resistant and dangerous choices” within virtual space. If, as Atkinson and Willis state, “real urban environments have become the source for game code while such games encode… the player interaction with real urban space” (2013), there is possibility that gameplaying may open a more testing and resistant expectation of real cities and inhabited spaces. One interviewee stating, “It makes me think I’d like to go down streets I don’t usually go down”.

For recent book Explore Everything, Place-Hacking the City, Bradley Garrett carried out research within the urban exploration movement. Urban exploration, as with parkour, skateboarding and other street activities, contests the ways we have been trained to inhabit the neoliberal city, going against the grain and asserting rights which have eroded. He describes sneaking out of a building site in the City of London having just climbed its summit:

“In our excitement coming back through the hole in the wall, we forgot to check first whether anyone was on the street and emerged in full view of a man in an expensive business suit, tie loosened, who stopped in his tracks…. As we turned the corner onto King William Street, I looked back and the man was climbing through the hole, in his suit. I was shocked and strangely honoured. He just wanted to be involved.” (2013, p.81)

The way that Garrett reads the city relates to that of Kevin Lynch who was suspicious of town planners dividing recreational activities into good or bad (1990, p.398). The contested city, expense of living and increased homogeneity of urban fabric may be contributing to people seeking leisure in solitary at home. Los Santos, and open-world games, may be considered as a reaction to this, the user confined into ever smaller urban dwellings using simulated experience of urban existence to carry out activities, freedoms and agencies they feel not permitted to do in real streets.

Los Santos may primarily be visited for leisure and escape from the everyday, but that does not mean that it cannot fulfil a function in suggesting other ways of existing. Lefebvre suggested that Charlie Chaplin created a “genuine reverse image” of modern times, but observed the growing leisure industry increasingly offering an illusory reverse image of “fictions of happiness” instead (1947, p.35). This tallies with modern-day use of simulation and CGI within the neoliberal city, used as it is in design, representation and marketing of property and place for capital investment, offering the illusion of buying history, meaning, power or happiness.

For Lefebvre, Chaplin’s created myth, where “criticism is not separable from the physical image immediately present on the screen”, directly reaches mass audiences using laughter to “stir up the masses profoundly” rather than calling for direct revolutionary action (1948, p.12). Benjamin considered passive cinema “introduces us to unconscious optics as does psychoanalysis to unconscious impulses”. With these ideas in mind, the emergent structures of the Grand Theft Auto series could be considered to operate as a genuine reverse image of our neoliberal society, with immersive experiences in which one is offered opportunity to critique political systems, capitalist structures and physical space. Reaching an audience of hundreds of millions of people, this could be a powerful proposition.

What we take with us from time in Los Santos and bring with us to the real cities we inhabit is what Edward Soja calls the Third Space (1996, p.10), a heterotopic “realimagined” space in which the slips, imports and segues between real and virtual of Atkinson & Willis (2007) become structural glitches in the creation of a new way of understanding of our relationship to physical space. As Baudrillard noted, the map now precedes the territory (1988, p.166) and interrogating and playing with the map may lead to new questions of operating in the real.

CONCLUSION

GTAV is many things: a mass-consumer ludic space of play; modern-day city-symphony of L.A; simulacrum of the real; work of art; mode of leisure; platform for learning about urban space; and a site for flâneurism electronique. Bereitschaft suggests that design games like SimCity “are likely to have a far greater impact on our urban world than any planning textbook” (2010) and as GTAV has now sold over 85 million copies (Nunneley, S., 2017), with Los Santos arguably one of the most visited cities of the modern age, the street level view of the walker should also be considered as a tool to impact our understanding of the urban realm in a similar way.

It may be the case that by spending more time in simulations like Los Santos as a response to being forced into our lounges from real streets that are too expensive, controlled and monotonous we are contributing to the emptying of the city, abandoning them to private organisations and state control. More optimistically, however, we could consider that Los Santos offers a training ground for a reconsideration of how we engage with urban spaces, a dismantling of the conformity and control that has shackled citizens to a neoliberal shift in rights to the city and expectations from it. If that training ground can coincide with other movements to reclaim the city, to explore everything, to reassert a public political agency over street and society then it could emerge as a key tool in introducing to a mass audience ways of being in the city which counter lived experiences.

A new edition of Grand Theft Auto is expected in 2020. The computer systems it will play on will be one generation on from those that run GTAV, and as such the depth, width, nuance and scope will be far greater, leading to a much deeper lived experience within place, character, authority and exploration. Elite was designed using 22kb of memory, thirty years later Los Santos used three-million times this to render its simulated world. The potential over the next thirty years for not only a wider, more nuanced territory to explore, but one which relies less on shorthand stereotypes to deliver script, as this genre and technology developers as early cinema did, suggests that we may have much to learn from Los Santos.

- The character of the flâneur was invariable a male character, created by men, read by men and to articulate a male rendering of place. See Flâneuse by Lauren Elkin (2016).

- See also Fest (2016) for a discussion on neoliberal market structures rooted deeply into the gameplay of SimCity BuildIt, a mobile version of the game and SimCity Limits in More Than a Game (Atkins, 2003, p. 125) and Kilson (1996) The Politics of SimCity.

- For a study on the role of perspective within the city from the Renaissance to the virtual, see Wyeld, T. & Allen, A., 2006.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atkins, B. (2003) More Than a Game. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Atkinson, R. and Willis, P. (2007) Charting the Ludodrome: The Mediation of Urban and Simulated Space and rise of the Flâneur Electronique, Information, Communication & Society, Vol. 10, Issue 6, 818–845R

Banham, R. (1971) Los Angeles, The Architecture of Four Ecologies. Berkely: University of California Press.

Barthes, R. (1981) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Howard, R. New York: Hill & Wang.

Bereitschaft, B. (2015) ‘Gods of the City? Reflecting on City Building Games as an Early Introduction to Urban Systems’, Journal of Geography, Volume 115, Issue 2, pp. 51–60.

Bernstein, J. (2013) ‘”Way Beyond Anything We’ve Done Before”: Building the World of “Grand Theft Auto V”’ Available at: https://www.buzzfeed.com/josephbernstein/way-beyond-anything-weve-done-before-building-the-world-of-g (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

Baudrillard, J. (2010) America. Translated by Turner, C. London: Verso.

BBC (2003) ‘Computer Gurus up for Award’, 9 January. Available at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/2642081.stm (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Bernstein, J. (2013) ‘”Way Beyond Anything We’ve Done Before”: Building the World of “Grand Theft Auto 5”’, Buzzfeed, 13 August. Available at: https://www.buzzfeed.com/josephbernstein/way-beyond-anything-weve-done-before-building-the-world-of-g (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Bogost, I. & KLlainbaum, D. (2006) ‘Experiencing Place in Los Santos and Vice City’, in Garrelts, N. (Ed.) The Meaning and Culture of Grand Theft Auto, Critical Essays. Jefferson and London: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Cardinali, L. (2009) ‘Tool-Use Induces Morphological Updating of the Body Schema’, Current Biology, Volume19, Issue 12, pp. R478-R479.

Debord, G. (1956) ‘Theory of the Dérive’. Translated by Knabb, K. Les Lèvres Nues #9

Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

De Certeau, M. (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Rendall, S. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Chesher, C. (2012) ‘Navigating sociotechnical spaces: Comparing computer games and sat navs as digital spatial media’, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, Volume 18, Issue 3, pp. 315–330.

Dominguez, M. (2004) The Role of the Flaneur in Jack Kerouac’s Novel On The Road. Masters of English Literature thesis. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande. Available at: http://www.lume.ufrgs.br/bitstream/handle/10183/14983/000672540.pdf Auto (Accessed: 7 December 2017).

Drive (2011) Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn [Film]. Los Angeles: Filmdistrict.

Elkin, L. (2016) Flâneuse. London: Penguin Random House.

Featherstone, M. (1998) The Flâneur, the city and Virtual Public Life, Urban Studies, Vol. 35, Nos. 5–6, 909–925.

Fest, B. (2016) ‘Mobile Games, SimCity BuildIt, and Neoliberalism’, First Person Scholar, 9 November. Available at: http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/mobile-games-simcity-buildit-and-neoliberalism/ (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Garrett, B. (2013) Explore Everything, Place-Hacking the City. London: Verso.

Gillespie, N. (2013) ‘Grand Theft Auto is Today’s Great Expectations’. Available at: http://ideas.time.com/2013/09/20/grand-theft-auto-todays-great-expectations/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

Graham, S. (2009) Cities as Battlespace: the new Military Urbanism, City, Vol. 13, №4, 384–402.

Hawthorne, N. (2011) ‘Critic’s Notebook: ‘Drive’ Tours an L.A. That Isn’t on Postcards’. Available at: https://www.webcitation.org/656mq1gKP?url=http://articles.latimes.com/2011/sep/22/entertainment/la-et-hawthorne-drive-20110922/ (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

Hill, M. (2013) ‘Grand Theft Auto V: Meet Dan Houser, Architect of a Gaming Phenomenon’, The Guardian, 7 September. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2013/sep/07/grand-theft-auto-dan-houser (Accessed 11 January 2018).

How Video Games Changed the World (2013) Directed by Al Camborn, Marcus Daborn, Graham Proud & Dan Tucker [Film]. London: Channel 4.

IGN (1998) ‘Grand Theft Auto’, 10 July. Available at: http://uk.ign.com/articles/1998/07/10/grand-theft-auto-5 (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Jacobs, S. (2006) ‘From Flaneur to Chauffer: Driving Through Cinematic Cities‘, in Emden, C, Keen, C & Midgley, D (eds.) Imagining the City, Volume 1. Bern: Peter Lang, pp. 213–229.

Jentsch, E. (1997) ‘On the Psychology of the Uncanny (1906)’, Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, Volume 2, Issue 1, pp. 7–16.

Katz, B. (2017) ‘Archaeologists in California Unearth a Large Sphinx From the Set of ‘The Ten Commandments’’, Smithsonian, 1 December. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/archaeologists-california-unearth-large-sphinx-set-ten-commandments-180967376/ (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Kolson, K. (1996) ‘The Politics of SimCity’, PS: Political Science and Politics, Volume 29, №1 (Mar) pp. 43–46.

Kim, M. & Shin, J. (2016) ‘The Pedagogigal Benefits of SimCity in Urban Education’, Journal of Geography, Volume 115, pp. 39–50.

Kleinman, Z. (2015) Do Video Games Make People Violent?, Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-33960075 (Accessed: 10 January 2018).

Kohler, C. (2011) ‘The Raunchy Parody Products of Grand Theft Auto 5’, Wired, 11 Febraury. Available at: https://www.wired.com/2011/11/grand-theft-auto-v-parodies/ (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Lefebvre, H. (1947) Title. 2nd edn. With new forward. Translated by Moore, J. London: Verso. Series and volume number if relevant.

Lefebvre, H. (1996) ‘Writings on Cities’. Translated and edited Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas

1996. Oxford: Blackwell

Leonard, D. (2006) ‘Virtual Gangstas, Coming to a Suburban House Near You: Demonization, Commodification, and Policing Blackness’, in Garrelts, N. (Ed.) The Meaning and Culture of Grand Theft Auto, Critical Essays. Jefferson and London: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) Directed by Thom Anderson [Film]. Los Angeles: Thom Anderson Productions.

Lynch, K. (1990) City Sense and City Design, Writings and Projects of Kevin Lynch. Cambridge, Mass. & London: The MIT Press

Lynch, K. (1960) The Image of the City. Cambridge, Mass. & London: The MIT Press

McDonough, T, (2002) ‘Situationist Space’, in McDonough, T. (Ed.) Guy Debord and the Situationist Internations, Texts and Documents. Cambridge, Mass. & London: The MIT Press

Merrifield, A. (2017) ‘Fifty Years on: The Right to the City‘, in The Right to the City, A Verso Report. London: Verso, Loc. 84. Available at: https://www.versobooks.com/books/2674-the-right-to-the-city (Downloaded: 11 September 2017)

McDermot, J. (2013) ‘Lifeinvader, Taco Bomb: Ad Parodies in GTA 5 Hit Really Close to Home’, AdAge, 15 October. Available at: http://adage.com/article/digital/lifeinvader-ad-parodies-gta-5-hit-close-home/244719/ (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Miller, K. (2007) Jacking the Dial: Radio, Race, and Place in “Grand Theft Auto”, Ethnomusicology, Vol. 51, №3 (Fall), pp. 402–438.

Miller, K. (2008) Grand Theft Auto and Digital Folklore, The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 121, №481 (Summer), pp. 255–288.

Murray, S. (2005) High Art/Low Life: The Art of Playing “Grand Theft Auto”, PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, Vol. 27, №2 (May), pp. 91–98.

Nilsson, E. (2008) ‘Simulated Real Worlds: Science Students Creating Sustainable Cities in the Urban Simulation Computer Game SimCity 4’, ISAGA2008 conference. Kaunas, Lithuania, 7–11 July. Available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.485.5139&rep=rep1&type=pdf (Accessed 2 December 2017).

Nunneley, S. (2017) ‘GTA 5 Ships 85 Million Units Making it the All-Time Best-Selling Video Game in the US’, Salon, 20 September. Available at: https://www.vg247.com/2017/11/07/gta-5-ships-85-million-units-making-it-the-all-time-best-selling-video-game-in-the-us/ (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Parkhurst Ferguson, P. (1994) ‘The flâneur on and off the streets of Paris‘‘, in The Flâneur. London & New York: Routledge

Petit, C. (2013) ‘City of Angels and Demons ‘, Gamespot, 16 September. Available at: https://www.gamespot.com/reviews/grand-theft-auto-v-review/1900-6414475/ (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Poremba, V. (2006) ‘Subversion and Emergencein GTA3’, in Garrelts, N. (Ed.) The Meaning and Culture of Grand Theft Auto, Critical Essays. Jefferson and London: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Redmond, D. (2006) ‘Grand Theft Video: Running and Gunning for the U.S. Empire’, in Garrelts, N. (Ed.) The Meaning and Culture of Grand Theft Auto, Critical Essays. Jefferson and London: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Rehak, B. (2003) ‘Playing at Being: Psychoanalysis and the Avatar’, in Wolf, M. and Perron, B. (ed.) The Video Game Theory Reader. New York: Routledge, pp, 103–128.

Ruscha, E. (1966) Every Building on the Sunset Strip. Self -published book.

Smith, E. (2017) ‘Grand Theft Auto IV Shows the Importance of Outsider Perspective’, Vice, 23 April. Available at: https://waypoint.vice.com/en_us/article/aepp9z/grand-theft-auto-iv-shows-the-importance-of-outsider-perspective/ (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Rivenburg, R. (1992) ‘Only a Game?: Will your town’ thrive or perish? The fate of millions is in your hands. Or so it seems. It’s your turn in SimCity.’, Los Angeles Times, 2 October. Available at: http://articles.latimes.com/print/1992-10-02/news/vw-391_1_electronic-game (Accessed: 3 January 2018).

Scimeca, D. (2013) ‘Grand Theft Auto Hates America’, Salon, 20 September. Available at: https://www.salon.com/2013/09/20/grand_theft_auto_hates_america// (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Soja, E. (1996) Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Sweet, S. (2013) ‘Idling in Los Santos’, Buzzfeed, 20 September. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/idling-in-los-santos (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Tavinor, G. (2011) ‘Video Games as Mass Art’, 5 May. Available at: http://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=616 (Accessed 11 January 2018).

Tea, M. (2015) The Urban Architecture of Los Angeles and Grand Theft Auto. Masters of Architecture thesis. University of Western Australia. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/18173221/The_Urban_Architecture_of_Los_Angeles_and_Grand_Theft_Auto (Accessed: 15 December 2017).

Van Horn, R. (1999) Violence and Video Games, The Phi Delta Kappan, Vol. 81, №2 (October), pp. 173–174.

Waldie, D. (2007) ‘Beautiful and Terrible: Los Angeles and the Image of Suburbia’, in Seeing Los Angeles: A Different Look at a Different City. Los Angeles: Otis Books

Ward, M. (2010) Video Games and Adolescent Fighting, The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 53, №3 (August), pp. 611–628.

Whalen, Z. (2006) ‘Cruising in San Andreas: Ludic Space and Urban Aesthetics in Grand Theft Auto’, in Garrelts, N. (Ed.) The Meaning and Culture of Grand Theft Auto, Critical Essays. Jefferson and London: McFarland & Company, Inc.

Wyeld, T. & Allan, A. (2006) The Virtual City: Perspectives on the Dystopic Cybercity, The Journal of Architecture, Vol. 11, №5, pp. 613–620.

Zeynep, T. & Zeynep, C. (2010) Learning from SimCity: An Empirical Study of Turkish Adolescents, Journal of Adolescence, Vol. 33, pp. 731–739.

(Image from:

(Image from:  (Image from:

(Image from: