Phantasmagoria & the Garden Bridge

Lapsus LimaEssay

2019

An long-read originally published in Lapsus Lima, on around strategies of image in neoliberal city making, available HERE and HERE.

PART 1: LONDON

LONDON

AS WORLD CITY

Changes to the built form of London since the strikes and economic downturn of the seventies have been arresting. So, too, is the changed reading of it as a city in the global consciousness. The bombed, urban core of the world’s largest empire was reborn in a spectacular explosion of architectural icons and burgeoning tourism, at the forefront of the emergent tech, financial and leisure sectors. It is the tale of an urban phoenix rising from its postindustrial ashes.

Some cities, like the Gulf coast megalopolises, configure their global identity around the desert-defying skylines of a new urban typology. Others, such as Venice or Prague, present as preserved in aspic; as if by simply gazing upon images of them, the viewer could reach back into a timeless past and enter an imagined historical truth. Both these visions, of sparkling modernity or untramelled history, are untrue and exist as marketable imaginaries; concealing a wealth of narratives. They do, however, illustrate how the projected image of place informs the distanced understanding of it globally.

With Roman, medieval, industrial and modern histories embedded in its streets, London has a unique presentation. Brand London is a montage of the past and future, an apparent offer of contemporary opportunity bursting forth from its imperial and architectural background. This abets its image as an attractive destination for the first-time visitor interested in heritage, and to returning tourists for whom the latest high-profile addition to the city’s fabric might merit returning. For businesses, too, the constant accretion of newness keeps the city interesting. In a world where global organisations can relocate with relative ease, the need for London to be constantly tweaking and besting itself is part and parcel of its World City positioning.

Another image of London exists concurrently to Brand London, and it is one comprised by digital imaginaries. Computer Generated Images [CGIs] present architectural propositions as existent and already integrated into the built city. Even pre-planning schemes can be shared to the press through hyper-realistic imagery that can be easily mistaken for photography. These pictures can be viralised with the swipe of a screen and they are craftily designed to promote and provoke, to conceal, excite and seduce. Their success in eliciting these affects translates into financing: unbuilt London property is bought and sold around the world solely on the back of CGIs and marketing spiel. A digital spectre shrouds the actual city (Minton 2017, 15-24).

Nine Elms Square CGI ©Glass Canvas for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 2019

Nine Elms Square CGI ©Glass Canvas for Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, 2019

The term “World City” was coined by John Friedmann in 1986 by drawing attention to studies relating to spatial changes resulting from global economic forces. He set them out in seven theses as “major sites for the concentration and accumulation of international capital” that “…bring into focus the major contradictions of industrial capitalism – among them spatial and class polarisation”. A key section identifies new emergent economies ―“corporate headquarters; international finance; global transport and communications; and high-level business services, such as advertising, accounting, insurance and legal”― as adding to ideological penetration and control through the “production and dissemination of information, news, entertainment and other cultural artefacts”. Friedmann noted that many of these professional services were engaged in international trade with global clients, and that cities were increasingly formulating self-presentations that played to these corporate and leisure audiences.

His hypothesis was later picked up on by Doreen Massey in her appraisal of London’s early neoliberal years after Thatcher’s closure of the Greater London Council and a free-marketisation illustrated no more powerfully than by the Big Bang deregulation of the financial system, both in 1986. What followed, under not just the Conservative governments through to 1997, but also during Labour’s Blair years, was a neoliberal project by which private capital took over once publicly-managed utilities and welfare state functions; putting a greater reliance on competitive individualism than the common, public good and shared resources. In Massey’s words, this was “more than a question of economics; it set the scene for a shift in a whole way of being. It is all this that has been the foundation of London’s reinvention” (2007, loc. 17%).

LONDON

AS TOWNSCAPE

The Brand London montage of traditional past and prosperous future was cemented during this period, when many older systems and structures —legacies of its relationship to empire and colonialism, or what Jacobs calls “Imperial nostalgias”— were folded into a new image:

“In the City of London, for example, imperial nostalgias are not simply present as a residual past. They are sanctioned and activated by conservation practises which influence, in most material ways, the very course the City takes into the future. Here as in the various other case studies, tradition is not simply about an escape from modernity but about negotiating modernity, about being modern. Indeed, it is precisely the desire to memorialise empire that has helped to drive the City beyond its traditional boundaries.” (2002, p. 159)

James Stirling’s No. 1 Poultry ©Historic England Archive, 2011

James Stirling’s No. 1 Poultry ©Historic England Archive, 2011

As Massey explains, the global economic shift resulted in a “spatial reorganisation” (2007, loc. 14%) from which World Cities emerged. The neoliberal process also reorganised at the lesser scale of architectural forms and materials. Jacobs cites the example of James Stirling’s Number 1 Poultry building, directly addressing John Soane’s Bank of England. A now Grade II* listed postmodern office building designed between 1985 and 1988, and completed in 1998, its form picked up on the neo-classical vernacular and street pattern of London’s financial district, developed as a scheme after a long-running saga in which developer Peter Palumbo finally gave up on his initial plans for a modernist glass tower.

Palumbo was under pressure from the Corporation of London and conservationist groups to adhere to a Townscape model of development that preserved —or, if possible, enhanced—the “architecture, skyline and distinctive townscape” of the city as a compositional, rather than individual, approach to urban design, informed by picturesque approaches to landscape and painting (Aitchison, 2012; Erten, 2008; Jacobs, 2002). Montaging of past and future helped create an ambiance which made space for historicism whilst allowing developments that met post Big Bang requirements for larger, open-plan office and trading spaces.

“The City of London… is noted for its business expertise, its wealth of history and its special architectural heritage. The combination of these three aspects gives the City a world-wide reputation which the Corporation is determined to foster and maintain… The City’s ambiance is much valued and distinguishes it from other international business centres.”

(Corporation of London, 1986, in Jacobs, 2002, 55)

Richard Rogers’ Lloyd’s Building ©Tony Hisgett, date unknown

Richard Rogers’ Lloyd’s Building ©Tony Hisgett, date unknown

Another spectacular singular moment of architecture, also incorporating montage and postmodern techniques, was Richard Rogers’ Lloyd’s of London offices, also from 1986. Following his interventions in the Parisian Marais with the Centre Pompidou, Rogers designed a hi-tech, avant-garde HQ for the insurance firm in a modern-day interpretation of Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace. In a style different to Stirling’s Poultry, it incorporated elements of the historic into its public-facing and internal spaces, described in the English Heritage (now Historic England [HE]) listing statement as:

“a purpose-built headquarters for an internationally important organisation that successfully integrates the traditions and fabric of earlier Lloyd’s buildings (including the Adam Room moved originally from Bowood House, the 1925 Cooper façade and fixtures such as the Lutine Bell)… the building, which looked to Victorian as well as mid C20 buildings for inspiration, firmly retains the splendour of its awe-inspiring futuristic design, 25 years (at the time of listing in 2011) after it opened… has many listed neighbours and it forms a wonderfully incongruous backdrop to many of these in captured vistas throughout the City…with international renown that cast the image of the City of London in a new light.”

(HE, 2011)

This was arguably the first piece of neoliberal architecture in the capital which could be designated as iconic, that is, as an “urban totem” representing extant power structures and “constituting new social relations as real or naturalised during moments of social, economic, or political change” (Kaika, 2011). London’s emerging neoliberal landscape in 1986 was such a moment, and Lloyd’s could illustrate Kaika’s remark that this type of architecture was “linked to the need to institute a new ‘radical urban imaginary’ for a new generation of elite power”.

LONDON

AS THE PICTURESQUE

“What we really need to do now… is to resurrect the true theory of the Picturesque and apply a point of view already existing to a field in which it has not been consciously applied: the city.”

(Hastings, 1944, p. 3)

As we can see from HE’s listing of Lloyd’s, the icon in London was formed around a townscape notion of juxtaposition, framing and relationships of form which carefully related the historic and traditional to the contemporary and experimental. The concept of the townscape derived from a campaign led from 1944 through to the mid-seventies in the pages of Architectural Review (AR) by its proprietor Hubert de Cronin Hastings, with support from editor Nikolaus Pevsner (Aitcheson, 2012).

Pevsner’s approach to visual planning sought to draw a through-line from Uvedale Price’s picturesque landscape movement of the 18th century into 20th century urban architecture. Together, Hastings and Pevsner thought that postwar modernism could be incorporated into a picturesque armature to create a more human townscape of varied textures, materials and admixed old and new. As with Price’s vision on landscape —detailed in his 1792 Essay on the Picturesque — this was territory to explore on foot, replete with unexpected turns, rough edges, clashes and experiences.

Price’s writings had, in turn, been a reaction against Capability Brown’s take on place, rooted in long vistas of a carefully controlled simulacrum of nature in which visitors had prescribed, linear paths extending into the private landscape.

“The borders of these walks are so thickly planted, and the rest of the wood so impracticable, that it seems as if the improver [Brown] said, ‘You shall never wander from my walks; never exercise your own taste and judgement, never form your own compositions: neither your eyes nor your feet shall be allowed to stray from the boundaries I have traced’ a species of thraldom unfit for a free country”

(Price, 338)

Price instead proposed softening edges, leaving extant natural or man-made elements in place and building an at least apparently more open path for visitors to navigate at will. Though in reality this shaping of place was no more natural than Brown’s, it looked more akin to an idea of rustic honesty. Not coincidentally, this shift in landscape ideals can be read parallel to the ruling classes’ concerns of revolutionary action; accompanied by a subtle reshaping of parliamentary politics, which made efforts to appear less paternalistic and more participatory (Bermingham, 1994).

St. Paul’s Cathedral ©Associated Press, 1945

St. Paul’s Cathedral was critical to the townscape movement; its epic isolation in the postwar rubble establishing it as the architectural beacon for a damaged but victorious nation. Its dome had affected planning policy around allowable building heights since 1935 and been a recognisable architectural moment of London ever since it cast its shadow on the ruins of the Great Fire in 1666. It was present in the art of Canaletto, and served as stageset for innumerable mediated events, from royal weddings to the Occupy movement. It is this embedding of a building into social history that buttresses its status as icon, its aesthetic qualities enclosed within a social meaning that enable it to work as a central component in “negotiating modernity” (Jacobs, 2002, 50).

As postwar capitalist, then neoliberal, London rebuilt over the second half of the 20th century, St. Paul’s became central to the picturesque rendering of its skyline. From numerous angles and locations, direct sightlines of the dome are protected by planning law, shaping the modern city around this nostalgic cultural artifact. The most recent Greater London Authority [GLA] London Plan outlines three types of strategic view ―“London Panoramas, River Prospects, Townscape Views”― while St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Palace of Westminster and the Tower of London are singled out for protection within Landmark Viewing Corridors and Wider Setting Consultation (2016, 300-306).

London Plan Viewing Corridors ©The Crown, 2016

Such sightlines have been considered in London planning for many years and are an immediate go-to regulation for campaigners opposing particular developments. One of the most celebrated views of London is from Waterloo Bridge, reflected by Landmark Viewing Corridors 8A.1 and 9A.1, and Viewing Place 15 in the 2016 London Plan. The panoramic vantage afforded at this bend in the river offers a view in which St. Paul’s can be read in relation to the growing cluster of City towers, which Günter Gassner states is “constructed as a historicist image as much as a world city image… The ‘new London skyline’ is best understood as a space that is defined by an ideology of economic growth and a static, highly limited framing of civic importance” (2017, 760).

St. Paul’s does not, of course, represent only civic importance. By proximity and association, its symbolic ties to the Empire, World War II and the Great Fire have also been absorbed by the collection of neoliberal organisations and institutions within the glass towers which are its present frame and backdrop. This is the creation of a picturesque moment through planning and strategy, with a relationship to picturesque landscape design in which sightlines to historic architectural moments, such as church towers, are incorporated into new landscaping to lend authority and rootedness to place and past.

Beginning with An Essay on Prints (1768), William Gilpin, a contemporary of Price, spread the notion of the picturesque in art. His writing offered guides for those embarking on Grand Tours of how to read and render picturesque landscapes, considering “the art of sketching is to the picturesque traveller, what the art of writing is to the scholar” (1794, 61). He looked to the works of painter Claude Lorrain and his compositional tool of the mirrorglass for reflecting a landscape and abstracting it into a frame. For Gilpin, the picturesque traveller had to seek out these framed views which were worth sketching from “all the ingredients of landscape – trees – rocks – broken-grounds – woods – rivers – lakes – plans – vallies – mountains – and distances”, emphasising the critical role played not only by form, but object composition.

William Gilpin’s view of Scaleby Castle, his birthplace, copyright unknown

William Gilpin’s view of Scaleby Castle, his birthplace, copyright unknown

It is this rendering of the picturesque ―as a device for structured sightlines and composed frames of view― rather than the AR’s proposition of using it to fashion meandering, experiential passage through place that became dominant in neoliberal townscape approaches. It has resulted in numerous picturesque frames of the City, including the sightline from Waterloo Bridge, which shape the World City imaginary of London. These offer postcard-views and marketable images of place which conform to Gilpin’s picturesque framing, making tradition and the historic its focus, with the glass and steel of the City’s financial towers standing, by proxy, for the nature of the original picturesque. In this context, St Paul’s plays the gothic folly or ruin in the country estate, offering its history, meaning and power to the surrounding architectural overgrowth. In Gilpin’s words:

“…the picturesque eye is perhaps most inquisitive after the elegant relics of ancient architecture; the ruined tower, the Gothic arch, the remains of castles and abbeys. These are the richest legacies of art. They are consecrated by time; and almost deserve the veneration we pay to the works of nature itself.”

View east from Waterloo Bridge ©Matt Perry, 2018

View east from Waterloo Bridge ©Matt Perry, 2018

Such is the World City image that London has come to embody, a temporospatial montage in a mediatable static form. It is not concerned with architectural or social complexity, but with providing a manageable, flat render of London as an easily projected message for global audiences. It is an urban pastiche which, Gassner suggests, is politicised not by its ingredients, but more by:

“the form of wholeness it encapsulates… Reducing the cityscape to a singular skyline and conceptualising it as a compositional whole is a neoliberal approach in that it is based on the belief that one must govern not because of but for the market. This is a crucial point, because… the visual protection of St. Paul’s… has increasingly been turned into a planning tool that benefits the construction of speculative new towers.”

LONDON

AND ST. PAUL’S

St. Paul’s dominance with relation to the forms that have been built around it has resulted not just in its framing across views and sightlines; but in the actual shapes of recent London architecture. By having to conform to planning sightlines, architects design around regulatory instructions, making unique geometries that allow clear sightlines of the dome. Whereas iconic megaproject architecture typically dominates its space ―its form not bound to historic precedent or context (Sklair, 2012)― London’s montaged townscape and its deference to St. Paul’s have led to forms which are ―or are at least marketed as― related to its history and context.

The Leadenhall Building, aka The Cheesegrater, took its form by needing to protect cathedral views from Fleet Street (Moore, 2016, 316), while the Scalpel has geometric wedges chiseled from its hulk to satisfy cathedral views. Other architecture, away from the City cluster, still relates its narrative to St. Paul’s. The Shard, in London Bridge across the river, was said by its architect to “kiss” St. Paul’s when seen from the protected views at Hampstead Heath (Moore, 2016, 318).

“Frames and perspectives. To be ‘framed’… is to be forced into another’s structure, a structure that’s not of one’s own. To ‘get things into perspective’ is to make sense of the confusing, the impermanent, the uncertain, to fabricate, to make what is three-dimensional into a two-dimensional effigy. To frame is to exclude, to select, to synthesise”

(Pugh, p. 33)

The Cheesegrater and St. Paul’s Cathedral ©British Land and Oxford Properties, 2019

The Cheesegrater and St. Paul’s Cathedral ©British Land and Oxford Properties, 2019

LONDON

AS A PRIVATE CITY

If “Form Follows Power” (Kaika & Theielen, 2006), then the rapid surge and dominance of these forms showcases the effectiveness of the marketable picturesque. St. Paul’s classical dome is visually nested within glass, which Gassner suggests helps “abstract from commodification and financialisation processes by drawing our attention to a story of success” (2017, 763).

The naming of these buildings also relates to London’s marketable aesthetic. The Gherkin, for instance, was a nickname given to Foster’s phallic tower by the public and the media, but developers picked up on its power, and more recent nomenclature —the Cheesegrater, the Pinnacle, the Spiral — was inscribed in the design offer alongside realistic CGI images, to give a soft face to aggressively commercial projects. This cultural and linguistic framing runs parallel to the aesthetic contrivance of an atmosphere around the development to show it in a certain light even before permissions have been granted or construction starts (Kaika, 2011, 984-985).

Though Kim Dovey’s book Framing Places Kim considered Melbourne, his meaning translates to London and other World Cities when he says: “As the corporate towers have replaced our public symbols on the skyline, so the meaning and the life have been drained from public space” (1999, 187). Architecture that’s invested in its relationship to the image of the city in toto often loses detail and relationship with the individual, at its own scale and at street level. It tends towards an exclusionary approach to the urban that sees public space replaced by its impostor, in the guise of Privately Owned Public Spaces [POPS], in a “slow expropriation of the city” (Ibid.).

The offer of new ‘public’ space has been folded into developer’s offers to be contributing to the community, in what are termed Section 106 agreements. This contribution may happen at ground level, as with Rogers’ Cheesegrater, where the tower is perched on piloti above a piazza acting primarily as a grand entrance for workers approaching the escalators. Increasingly, however, the ‘public’ space is at the top, providing vast panoramas of London that arguably serves tourists more than residents.

Rafael Viñoly Walkie Talkie building on Fenchurch Street went one step further. Its bulbous, glazed top floors ―a vast, tiered public garden and viewing platform― were advertised as “London’s tallest public park” ―though it was high, not tall; a garden, not a park, and private, not public. It features a planting scheme which can be read against Jacobs’ notion of imperial grandeur via neoliberal aesthetic, generously described by management as: “Tree ferns and fig trees recreate a lush prehistoric forest, whilst Mediterranean and South African flowers suggest a sinuous mountain ravine” (Sky Garden, 2018b).

The result —after developers put in twice as many cafés as agreed, and built a corporate patio-with-planters feel rather than the Babylonian vision of the CGI renders — was felt by many to not quite reflect the offer.

Fenchurch Street Sky Garden, CGI v. Reality (l) ©RVAOC/20 Fenchurch Street, (r) ©The Guardian

Fenchurch Street Sky Garden, CGI v. Reality (l) ©RVAOC/20 Fenchurch Street, (r) ©The Guardian

The public does have access to Sky Garden, but only with online pre-booking for timed slots of an hour and photo ID required, lest they have a reservation at a restaurant. As is the case with the growing number of London POPS (Minton, 2012, loc. 1161), access comes with a long list of rules and regulations: management reserves the right to check your name across police databases and restrict access if you have a criminal record; you will pass an airport-like security check with restrictions on liquids; children under 16 must be with a ‘responsible adult’; and they will not be responsible for injuries in the event of nuclear disaster or war (Sky Garden, 2018a).

Though you won’t be allowed to bring your own food or drink into this ‘public’ space, and may be removed if presumed to be under the influence of alcohol, there are five food and drink concessions squeezed in at the rooftop, where reservations can be made to enjoy wine from £9 a glass, £14 cocktails, a £19.50 beef burger or monkfish for £30.

The Walkie Talkie Interrupting protected sightlines ©The Architects’ Journal, 2016

The Walkie Talkie Interrupting protected sightlines ©The Architects’ Journal, 2016The Walkie Talkie was only allowed to be constructed at all —in a location which did not merely interrupt protected sightlines, but also broke away from the cluster development model— based on this ‘public’ return exempting it from normal regulations. It has been suggested that another reason for its permitting was that City authorities wanted to extend the cluster southwards by opening up a huge new section of the city for potential redevelopment. Indeed, the gap between the Walkie Talkie and the City cluster now seems ripe for infilling, especially considering previous instances of allowing towers where there’s distance between others to be filled and create picturesque clustering. A planning officer has said, “what you want to do is fill in the missing tooth, because isolated buildings compete with St. Paul’s” (Gassner, 2017, 76).

This can be considered a landgrab of public space —with space including open-air and sightlines, as well as groundspace— by allowing the free-market to take ownership of it because their ‘public’ offer would trump the protections built into existing regulation. There is a precedent for this, again with Stirling’s No. 1 Poultry, the scheme of which included a circular drum form on the roof which blocked protected views of St. Paul’s along Cornhill, but which is described by HE as “…not just a view of St. Paul’s from afar… [but also] ideal to give a sense of London as the economic centre of the Empire as well as the spiritual and other-worldly sense of the Empire” (Jacobs, 2002, 50).

With the cathedral in mind, the developer said that —though the drum would block protected views— it would echo the dome’s proportions “in absence”, with the roof garden offering never-before-seen vistas of the cathedral (Jacobs, 2002, 57). Said ‘public’ space is now a Coq d’Argent, with mains starting at £19.

View from the Coq d’Argent, No. 1 Poultry ©eastlondongirl.com, 2019

View from the Coq d’Argent, No. 1 Poultry ©eastlondongirl.com, 2019

LONDON

AND ENVIRONMENTAL SPECTACLE

The Walkie Talkie and its deployment of ‘nature’ can be seen as part of a trend of planting and landscaping which evolved from nineties responses to climate change within the built environment. After the 1972 Stockholm Conference and the creation of the United Nations Environment Programme, notions of environmentalism were embedded into many sectors, including architecture, and this was further developed through Edward O. Wilson’s biophilia hypothesis, which suggested “that the urge to affiliate with other forms of life is to some degree innate”, and proposed a human approximation to this across all areas of living (Wilson, 1984, 85).

By the mid-nineties, this had developed not only into an industry and ideological design discourse, but resulted in new standards and charters on carbon neutrality and the development of symbiotic relationships between cities and nature (Herzog, 1996). This ecological and progressive approach to urban design is still present in many architectural and political sectors though, by the turn of the millennium, green had been absorbed into spectacle. Initiatives such as the Eden Project and the sensuous biophilic forms of Calatrava were becoming more spectacular, using ecological awareness as a marketing ploy rather than offering any built response to climate change.

Schemes such as London’s Strata tower —with three wind turbines built into the peak of a block which would have otherwise not likely been permitted— were accepted. The turbines ran for three months before being turned off for good (it was suggested penthouse occupants complained of the noise). They have not rotated since, but remain a stain on the skyline, reminders of the folly of perverse green lies.

The Strata Tower ©Getty Images, 2016

It was also in this period, between 1997 and 2000, that the London 2012 Olympic bid was being prepared; a regeneration project using media-friendly greening and biophilic language as part of its “legacy” offer. In 2005’s submission bid, it was stated the project would “contribute to a model for environmental sustainability applicable to cities in both the developed and developing worlds” (London 2012 Ltd., 2005, 23). However, its green credentials have been criticised (Minton, 2012, loc. 38-491; James, 2018, 247-260) as an aesthetic to facilitate neoliberal development in a manner not dissimilar to how City projects have availed themselves of ecology, nationalism and privatised spaces to smooth the passage of planning.

“Some of those claims were of course true, but they also functioned to mask the more determining capitalist and jingoistic imperatives for the Park. The Games were inexorably tied to enormous capital investment, and to the failure or success of a nation. The flourishing grasslands, riverbanks, and nesting holes for sand martins were at the same time window dressing for a nationalist regeneration machine that would succeed at all costs”

(James, 298)

The Olympics can be seen as a vast and costly conflation of environmental appearances to service neoliberal urban development, using nationalism and ideological positioning to support and defend it from criticism. Emma Street (2014, 67) highlights how, since the recession of 2008, and “in a context of deepening ecological and economic scarcity, the [government] calls for the contribution the natural environment makes to quality of life and economic success to be quantified in economic terms: ‘valuing nature properly holds the key to a green and growing economy’.”

Ten years on, the financial climate has not structurally changed and, if we live in “an economic world constituted from gargantuan amounts of public and private debt that is sustained by the policy machinations of central banks” (Thompson, 2017) —which means we are effectively still in the 2008 crash, if not heading towards a repeat— then London’s architecture and World City image belie the truth of climate and financial breakdown.

Likewise, if we are in a more precarious ecological global state now than in the nineties, ‘green’ architecture now conveys an image of recovery more than any real, rooted crisis response. The representation of financial and imperial power in architecture can be likened to representations of environmental ‘improvement’, such as the Walkie Talkie, urban planting schemes and biophilic mimicry. As David Harvey says, “far too much of what passes for ecologically sensitive in the fields of architecture, urban planning and urban theory amounts to little more than a concession to trendiness and to that bourgeois aesthetic that likes to enhance the urban with a bit of green, a dash of water, and a glimpse of sky” (2001, 42).

The deployment of nature in such urban contexts can also be read as a softening of the harsh, authoritarian architectures, materials and ideological systems of the neoliberal period. Adding a “lush prehistoric forest” —or at least the aura of it— to a scheme can ameliorate it in the eyes of planners ―while aiding the World City image of London.

In the 2016 London Plan, the word ‘sustainable’ is used in relation to the following: ecology, social, economics, water, population growth, development, drainage, quality of life, business opportunities, innovation, creativity, health, education, research, culture, art, regional and local success, regeneration, lifestyles, retail, access to goods, travel, communities, neighbourhoods, environment, residential quality, design and construction, distribution, electricity, gas, materials procurement, construction, retrofitting, waste management, spatial development, and use of World Heritage Sites. In short, it can be applied to every element of citymaking and, as such, it is an easily adjustable term in the marketing and presentation of developers who want a buzzword that can mean anything and very little. Nature, sustainability, ‘green’ and suggestions of ecological concern are now seamlessly folded into the development package not just as an add-on, but as a function of smooth delivery and image making (Konijnendijk, 2010).

“Although the rhetoric has changed and new concepts like “sustainability” have become fashionable, the deep anti-urban sentiment combined with an idealised and romanticised invocation of a “superior” natural order has rarely been so loud. Much of these debates about restoring a more environmentally sound urban fabric ignore the very foundations on which the contemporary urbanisation process rests” (Kaika & Swyngedouw, 570)

PART 2:

THE GARDEN BRIDGE

THE GARDEN BRIDGE

AS AN OBJECT

CGI render looking from the Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

CGI render looking from the Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013The Garden Bridge may be the most spectacular and controversial ‘green’ urban intervention proposed for London, incorporating many of the concerns described in Part I into a grand projet designed to assist the image of London as World City. The project, by Heatherwick Studio, was pitched to Boris Johnson, then Mayor of London, in 2012; on the back of Heatherwick’s success with the Olympic Cauldron, a kinetic structure in which numerous petals closed together during the nostalgic opening ceremony (Oettler, 2015) to form the symbolic flame of the occasion.

Though the Mayor of London is responsible for creating the London Plan, shaping overarching approaches to urban development, they have little agency to impact architectural interventions. One coffer they can access is that of Transport for London [TfL], so that if they wanted to lead on a grand project, they would need to invoke a tangential transportation function and collaborate with other agents (Swyngedouw et al., p. 215).

Spectacle is Heatherwick’s stock in trade, with a back catalogue slowly evolving from product design to megaproject architecture by way of temporary interventions, including Britain’s “hairy” Seed Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo. This shift into urban design didn’t come without some costly, publicly-funded hiccoughs, among them, a sentimental reinterpretation of the Routemaster bus that was discontinued after numerous, expensive design and technical failings; the B in the ‘Bang’ installation, eventually melted down and sold for scrap by Manchester Council after javelin-sized metal spikes began to break off from it, and the Blue Carpet public space in Newcastle, an experimental blue-glazed paving which began to crack and fade to grey almost immediately. But none of this knocked Heatherwick’s confidence, as suggested by a New York Times profile noting how he “largely avoids self-depreciation” (Parker 2018).

Will Hurst, Managing Editor of London’s Architects’ Journal [AJ], says Heatherwick “certainly knows how to pull the levers of power”, and these were certainly pulled in 2012, when Johnson grabbed the Garden Bridge idea and did all he could ―down to creating an alleged illegal procurement process― to propel it into realisation (Smith, 2015) through TfL and the Garden Bridge Trust [GBT], a charity. The project had been developed from an initial idea by celebrated actress Joanna Lumley to build a bridge with trees on it as a 1998 memorial to Diana Princess of Wales. Lumley was a friend of Johnson, which aided access to the Mayor; and what started as a personal fancy had, by 2013, turned into a serious proposal costed initially at £60m, to be entirely privately funded, and with a location decided upon immediately to the east of Waterloo Bridge, with little rationalised justification.

CGI of the Garden Bridge from Waterloo Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

CGI of the Garden Bridge from Waterloo Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013Heatherwick described the bridge as “just two planters, their foundations sprouting from the river bed” (GBT, 2015), with each reaching a width of 30m to support two planted areas of trees, the tallest of which would reach 15m following 25 years growth. Lumley spoke of “[w]ild paths [which] will snake around woodland copses and glades” (2014a) meeting in the centre of the bridge, where it narrowed to 6m. At the north side, the crossing would land on the roof of Temple Underground station and, to the south, a new commercial unit would be built on existing publicly-owned park, the roof of which would be a 600sqm area with a “Disney queues system” for crowd management (GBT, 2014b, p. 18). These two ends could be closed off, to enable the privately-owned project to be let out for up to 12 days a year for corporate fundraising, as well as closing between midnight and 6am.

Much was said by its proponents to the effect that this would be a green addition to the city, Lumley even declaiming it would have a “dreamlike, almost […] magical quality, to be able to walk through trees and grass, with birds and bees, over the river in the centre of a huge vibrant city” (2014a). She frequently invoked an urban oasis, implying the bridge’s powerful function as a tool of social appurtenance to urban forces, where visitors could “maybe slow down, hear birds singing, hear leaves rustling, get a little bit of calm, take the heat out of the situation, [it can] make people feel a bit more generous about making London a more beautiful place for everybody who lives here” (Lambeth Council, 2014).

THE GARDEN BRIDGE

AND IMPERIAL NOSTALGIA

The Garden Bridge can also be read as a furthering of Jacobs’ colonial reading of the City. As part of his carefully manufactured public image, Johnson regularly invokes nationalistic tropes and turns of phrase, from writing a biography of Winston Churchill through talking of the Commonwealth in terms of “flag-waving piccaninnies and watermelon smiles” (Johnson, 2002a), and stating that it was a problem Britain was no longer in “charge” of Africa (Johnson, 2002b). Brexit, his next large project after the Garden Bridge, was also wrapped up in the concepts and semantics of colonial nostalgia (Younge, 2018).

Following the 2010 Shanghai Expo and the 2012 Olympics, Heatherwick was being internationally paraded by the British Council [BC] with a deeply uncritical exhibition that visited Asia and the USA (BC, 2015). Ichijo states the BC is “a legacy of British imperialism which is trying to adjust the post-colonial, increasingly global world” by working with “the politics of identity maintenance in a former colonial power in Europe” (2012), and Heatherwick’s movement into spectacular architecture fit not just Brand Britain, but also the exportation of Britishness and the reinforcement of London’s World City image. Just as the neoliberal towers shining in a cluster tell the world that London is a continuing success story, so too this “green corridor” was “strengthening London’s status as the greenest capital in Europe” (Emmott, 2015).

Lumley was born in Kashmir, her father a Major in the WWII Ghurkha regiment and her mother from a lineage of politics and military service in colonial India. Her father’s side of the family were deeply rooted in the British colonial project, including her great and great-great-grandfathers holding senior positions in the East India Company (Barratt, 2007). Throughout his book The Country and the City (1973), Raymond Williams parallels the idea of childhood with an illusory vision of nature, and Britain: “The natural images of this Eden of childhood seem to compel a particular connection, at the very moment of their widest generality. Nature, the past and childhood are temporarily but powerfully fused” (1973, p. 139). Lumley’s mirage of Eden, the Garden Bridge, is directly informed by her own childhood memories growing up in former British colonies, placing Jacob’s imperial observations of London architecture at the heart of the Garden Bridge project:

“My sister and I got up very early the first morning and the gardens were surrounded with extremely thick white clouds. There were roses, cabbages, runner beans with great scarlet flowers, tangles of onions, tall things growing — an island of tropical plants floating in the air. I was seven and it had the most enormous impact of anything in my childhood.”

(Lumley, 2014b)

Williams notes “only other men’s nostalgias offend” (ibid, p. 12), and so it was the case as the proposed built form of Lumley’s romantic memories were less well received than expected. There were many reasons for the local community and experts ―from procurement, architectural, legal and political sectors― to oppose the Garden Bridge (Jennings, 2016a); including that it would be another London POPS, an undemocratic site of human and technological surveillance with a long list of regulations affecting access and use.

Popular concern was raised about these proposed rules (Alter, 2015; Dunn, 2015) reflecting concerns raised by academic Anna Minton, that “spaces are regarded as democratic because everybody can use them, which means that if the ‘reclaimed’ public realm is no longer space everybody can use, we need to worry, not only about the state of our cities, but about the state of our democracy” (2012, loc. 1429).

THE GARDEN BRIDGE

AND THE ENVIRONMENT

The GBT rarely claimed their project was environmentally beneficial to London, except for claims the Garden Bridge was an “ecologically sustainable corridor to encourage pollination and biodiversity” (GBT, 2015) that failed to explain just what was meant by “sustainable”. London Beekeepers disagreed, saying bees would stay clear due to winds, while other green organisations ―including the Green Party, Trees for Cities and London Wildlife Trust― also criticising the project’s ecological aspects (Jennings, 2016b).

Spencer writes that the construction of neoliberal architecture “is disguised in the phantasmagoria of smooth surfaces and elegant forms wrapped around its structural armatures” (2016, loc. 308), and so it was with the Garden Bridge that its great hulk of steel and concrete would be wrapped in £10m of glistening cupronickel ―a metal Lumley described as “easily the most expensive thing you could clad it in, easily” (2014c)― donated by Glencore, a mining conglomerate with presumed links to child labour, mass pollution, bribery and paramilitary murders (South Bank Tales, 2016).

The GBT also claimed that “the green infrastructure created… will contribute towards the mitigation of climate change through its planting scheme and features such as rainwater collection areas” (GBT, 2014e, p. 14; 2014c), seemingly unaware that if they didn’t build across the river then the rainwater would simply be collected into the Thames. Mostly, the case was made for it being an iconic symbol of a green future, “maintaining and improving London’s image as the world’s most green and liveable big city” (GBT, 2014e, p22). Just as the dome of St. Paul’s represented less spiritual or historic connectedness and served more as a useful signifier to propagate colonial and national identity in a global landscape, the ‘green’ aesthetic of the bridge would have acted as a distraction from the serious environmental concerns in the city; with streets in Lambeth, where the Bridge would have landed, reaching annual EU pollution limits in the first 30 days of 2018 (Gabbatiss, 2018).

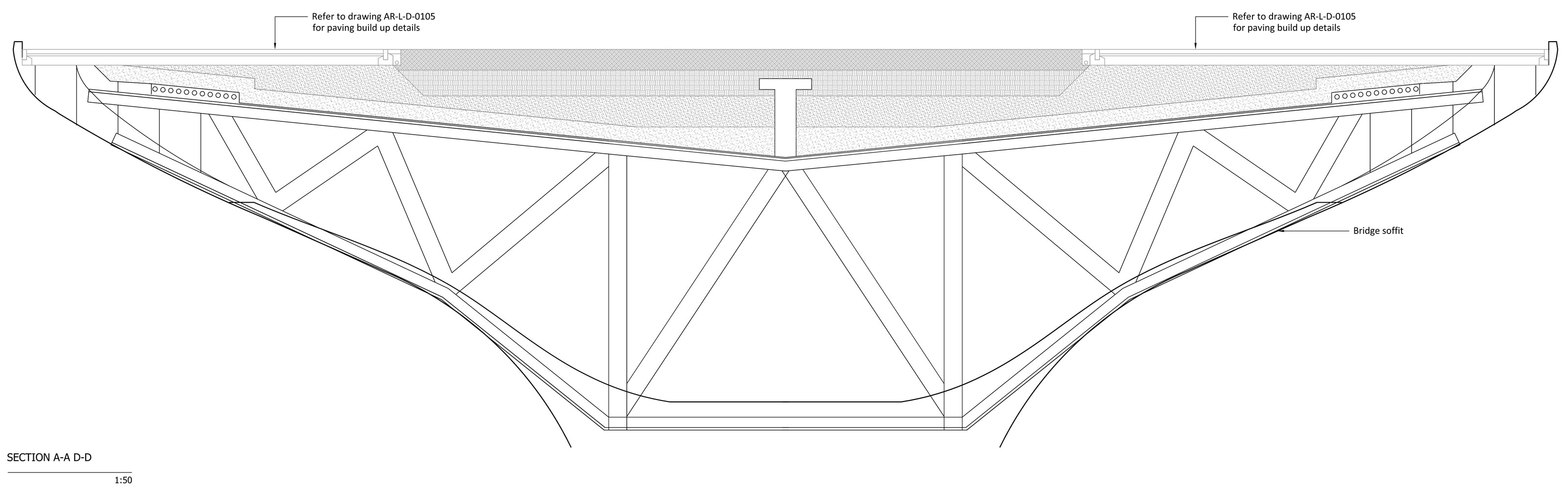

Cross section of the Garden Bridge structure to be wrapped in cupronickel ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

Cross section of the Garden Bridge structure to be wrapped in cupronickel ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

“It is almost as if a fetishistic conception of “nature” as something to be valued and worshipped separate from human action blinds a whole political movement to the qualities of the actual living environments in which the majority of humanity will soon live.”

(Harvey, 2001, p. 40)

Opponents didn’t dispute that green spaces, despite not having more profound ecological credentials than simply offering a greener feel to the city, could not serve other purposes, among them mental health and social capital (Braubach et al., 2017). They were more concerned that the developers were availing themselves of the language and aesthetics of such desirable outcomes to enable a private project requiring large amounts of public money and damaging public commons, which would primarily benefit property and rent value on both banks of the river.

The estimated cost of the endeavour peaked at “north of £200m” before the whole thing was cancelled in August 2017 after the GBT found too many financial, political, procedural and legal hurdles in its path―but not before £46m of the £60m public funds allocated to it had been spent on design, planning, legal and promotional work―. Detractors suggested this kind of money could have made a meaningful dent in the environmental issues London faces, had it been spent more strategically and with genuine environmental impact in mind.

THE GARDEN BRIDGE

AND SIGHTLINES

“The bridge would create a new iconic form that responds to and enhances its unique Central London context… The overall massing of the bridge would contribute to the townscape and frame historic views of London.”

(GBT, 2014a, p. 50)

Despite the plans requiring the concreting over of a small but appreciated public greenspace on the Southbank, the GBT promoted their development as bringing new public space to a much-needed part of the city, in an area Johnson described as “nobody thought you could exploit, over the river itself” (GLA, 2015, p. 1). The word “exploit” fed into concerns about the project being a smokescreen for private capital uplift (Johnson, 2015; GBT 2014e, pp. 127-131). It also related to ongoing concerns for rights to the city and the notions of urban commons. The protected open views from Waterloo Bridge and the Southbank ―effectively public space en plein air― would be adversely affected against London Plan guidelines due to a private development; in effect, an enclosure of space which privatised extant and historic public panoramic views was opposed as vehemently as privatisation of public land had been in the past.

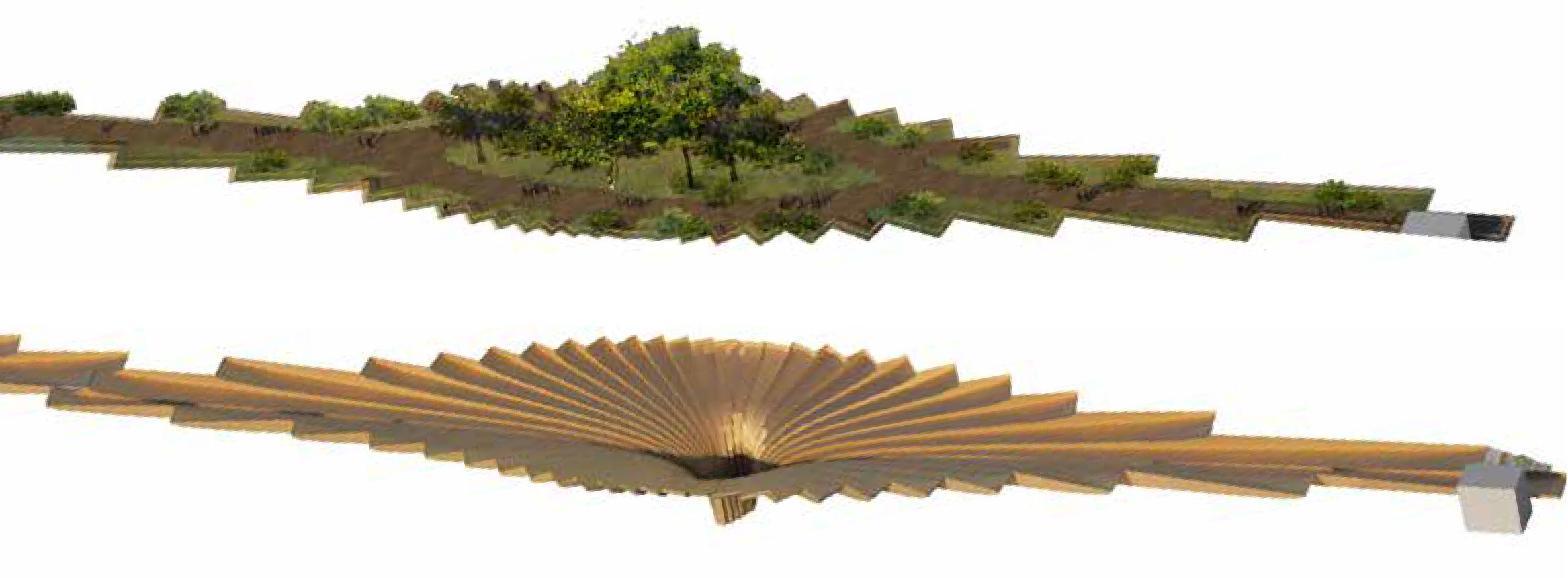

The Garden Bridge, CGI image showing radial layout and planting ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

The Garden Bridge, CGI image showing radial layout and planting ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013When a Londoner walks across Waterloo Bridge the city is in flux, its overlapping architectural forms kaleidoscoping in a play of light with the individual’s experience of movement and air. For a flâneur crossing the Thames, the skyline and the City are a personal rendering of shifting form. The GBT acknowledged that existing views towards the city ―a part of London’s evolving heritage since the construction of the first Waterloo Bridge in 1818― were “highly valued for the unspoilt curved sweep of the river with a diverse and recognisable skyline as a backdrop”, but suggested they could “re-create” them further downstream (2014d, p. 70).

Crucially, the views from the Garden Bridge were to be experienced statically from “key rest points [offering] carefully composed views out onto the river and surrounding cityscape” (2014a, p54). Heatherwick claims to have taken inspiration for this from the film Titanic’s scene in which Leonardo di Caprio and Kate Winslet squeeze into the bow of the deck to enjoy a personal, expansive view. The “rest points” on the Garden Bridge, formed from the radial plan of each “planter”, were designed for visitors to stop and passively receive an image of the city as a frozen slice of time, with the iconic forms of London’s neoliberal skyline as a postcard moment. Heatherwick said the Garden Bridge would be “the best place to see London from” (Bell, 2015), with the implication Londoners should sit back and receive an image of their city at a safe remove, rather than as citizens actively experiencing and engaged with it.

“Someone called [the Garden Bridge] a vanity project. But it’s not. And what was the biggest vanity project ever in London? Probably St Paul’s Cathedral. There was huge resistance to St Paul’s being built.” (Heatherwick, in Walsh, 2015)

CGI render from Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

CGI render from Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013Heatherwick and Johnson frequently invoked St. Paul’s Cathedral as a natural predecessor of the Garden Bridge, by asserting that since its construction had some opposition in its time, then logically all opposed developments would be similarly as important. They stated that the Garden Bridge would become so central to London’s heritage that in “1000 years’ time people will still be using it” (Heatherwick, in Frith, 2015).

The cathedral is not only semantically woven into the Garden Bridge’s narrative ―views of it are key to its aesthetic form―. From the centre of Waterloo Bridge (where, after 25 years, the planting was intended to have reached full growth), St. Paul’s Cathedral would be nestled within the former’s two artificial copses; a classical, symbolic moment of London’s history cradled by nature, and set in front of the successful, modern backdrop of the City’s iconic cluster

This is a vision of pure picturesque which would undoubtedly compose a striking image for London to present to the world: a re-iteration of its montage of nostalgia, future, spectacle and triumph, albeit as a static representation of place aimed more at its status as a corporate and world city than at any public, community or environmental benefit (despite Lumley discussing the project as a benevolent “gift to London”).

THE GARDEN BRIDGE

AND THE DIGITAL SUBLIME

As with so many modern development projects, the Garden Bridge relied immensely on mediated CGI to generate public and philanthropic interest and persuade authorities and stakeholders. The first images of the proposal as a complete architectural proposal were released in June 2013, surprisingly soon after Heatherwick was awarded a £60,000 award for a feasibility study into whether a footbridge was needed in any central London location only three months prior. Without any design competition or public call for a bridge in this location ever being made, the images of the Garden Bridge hit the media suddenly, and it appeared in them as if this crossing could drop into the centre of the capital as easily as the renders appeared on screens.

CGI render of Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

CGI render of Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013In a view looking east along the Thames from a slightly raised perspective, a higher-than-human-gaze ―that would be revisited to present the project― showed the fully-grown trees in a summer evening glow, St. Paul’s centre frame with the glass towers of the city behind it. Alongside it, two other images were published. One, from the Southbank ―a rare human-vantage towards the bridge― featured the HQS Wellington, built in 1934 and used in the evacuation of allied troops from French beaches in 1940, under the bridge; an imperial framing to match that of St. Paul’s in the panoramic render.

The other, from the narrowest point in the bridge, looked towards one of the copses, bathed in a soft, chalky atmosphere, as a surprisingly low number of people occupy the space. Though the design and use of images changed over time, the tropes of imperialism, rootedness, the function of people in the images and their sublime atmosphere remained as techniques for selling the vision throughout.

Left: HQS Wellington and the Garden Bridge. Right: view from narrowest point of the Bridge, both ©Heatherwick Studio, 2013

Left: HQS Wellington and the Garden Bridge. Right: view from narrowest point of the Bridge, both ©Heatherwick Studio, 2013The deployment and function of CGIs became more essential to the GBT ―which scarcely engaged with the public save through imagery and press releases― as the project developed. But the scenes ―of a serene, pastoral and relaxing space in the centre of urban business― married to the persuasive, optimistic language used by Heatherwick and Lumley, didn’t tally with the architectural, environmental and community voices describing an alternative expected outcome.

Media reporting on the hurdles the GBT faced ―even opinion pieces highly critical of the development― were almost always accompanied by one of the seductive CGI renders. Just as the role of the design was to be dominantly iconic in the centre of the city, if built; so too the images would be iconic in printed or digital media, an architectural clickbait which, with constant viewing, would only become more embedded into the collective consciousness. Within a media marketplace in which images dominate traffic and content, many who saw them repeatedly would not read the articles or adjoining criticism, and so the powerful, lingering aura would be that of the picturesque image.

Journalists stated they did not have the power to choose which images were used, that this was the function of a picture editor, even if the image compromised the message of the text beside it.

The Garden Bridge after Year 1, from the Planning Application ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

The Garden Bridge after Year 1, from the Planning Application ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2013

Of course, a picture editor needed only open the planning documents (GBT, 2014a) to see a wider selection of images showing the project in a less idyllic atmosphere. But though they could have aligned with the journalism conceptually, these images don’t have the punch of the artfully cropped, designed and framed CGI renders. The sublime and the picturesque are still dominant in image making, choosing and reading, especially in a struggling media landscape which needs visual hooks to generate clicks or buy-ins. And so, in choosing these images to illustrate a critical news article, the media organisation did exactly what the Garden Bridge’s developers and masterminds required. The medium is the message, and in a visually prevalent, image-devouring culture, the message set forth by the CGI was more powerful than any critique accompanying it.

The publicly disseminated digital images have a sense of the uncanny. The time is always high or near-high tide, the sun is always rising or setting, there are never crowds in them but ―of those images that do have people― they are mainly couples or families, usually lingering or leaving and admiring the distant view, or examining planting; reflections of Lumley’s “half dream world” (2014d). But while the images show sparse and peaceful vistas, without the sense of being in the middle of a huge tourist attraction, the numbers in the planning documents suggest otherwise.

They state the Garden Bridge would aim for a Pedestrian Comfort Level B similar to a shopping street and explained, in TfL guidance, as “people start to consider avoiding the area” (TfL, 2010). Around the Southbank, crowds would sometimes reach Pedestrian Comfort Level D or “very uncomfortable” (Moore, p. 384). Yet the renderings showed a clear expanse of empty space which you ―the future user dropped into the spectral future― can explore at your leisure. The Garden Bridge was promoted as both an empty space in which to hear bees and water, and a major World City for over 7 million people a year; as a place in which to pause and dream, but also as a critical route for commuters to rush to their office from Waterloo Station; as a grand, iconic statement into the London skyline, but also as a delicate and sublime knitting-together of the city. In short, the project depended on the disjunction between instant image and harder-to-digest detailed information, using the visual as a veneer to layer over the clunkier truths beneath.

A CGI scene of the Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2015

A CGI scene of the Garden Bridge ©Arup/Heatherwick Studio, 2015

When facing the strongest pressure from all those who opposed or critiqued the project, the GBT released new imagery. In December 2015 they disseminated a “winter scene”, in an apparent attempt to counteract criticism that it was always summer on the Bridge and that it served no function as a useful transport route. The ten people present in the CGI were not dawdling, but intently walking in serious business attire, as if to show the Bridge as a critical piece of infrastructure to London’s financial future. In contrast to previous renders ―mainly populated by couples, families and curious tourists― only two of the ten characters featured were a pair, and even they were looking straight ahead and not at each other. One person tangentially glances at the view off the bridge; another is looking at their phone to signify activity and connectivity. These are important people rushing to work, fuelling the city and powering the economy, and the image says, “we are the moment of respite, nature and pleasure before the graft of the modern office”. Here, again, within these characters, the relationship to power and the city is made evident as a structural element in the construction of London imaginaries. Green writes about this immediacy and how wrapped up it is in the contemporary urban narrative:

“In the morning you are gambling on the stock exchange or seated at Tortoni; by the afternoon you are walking solitary among woods and fields, watching the sun set behind the trees. It is precisely that counterpoint between moving (physically) away from the city and yet remaining in touch with it which gives a distinctive shape to the urban experience of nature.”

(Green, p. 93)

Artist Alberto Duman calls the characters who populate CGIs ghosts in reverse, “their visual presence performs a deliberate act of prefiguring the occupation of future… anticipating their existence in affirmative and expressive ways through projected identity and lifestyles, actions and positions in public space.” (2018, p. 148). These renders are part of what Gernot Böhme calls the aesthetic economy, starting out “from the ubiquitous phenomenon of an aestheticisation of the real, [which] takes seriously the fact that this anaesthetisation represents an important factor in the economy of advanced capitalist societies” (2003, 72).

He goes further, to say that it gives “an appearance to things and people, cities and landscapes, to endow them with an aura, to lend them an atmosphere”. CGIs have a particular aesthetic and mode of production (Rose et al., 2016) which lends itself to the atmospheric, utopian glow of neoliberal development and economic forces.They are smooth, impenetrable and sublime in a manner not dissimilar to the fantastical glass and steel forms of global finance in the London skyline that reflect both St. Paul’s and the passers-by, what Simpson calls “a dialectical image counterposing the utopian dreams of the collective against the neoliberal delusions of fictitious and hyperreal capital” (2013, p. 366):

“part of their glamorous atmosphere derives from the glow of unwork that permeates them. Like movie special effects and computer games, digital visualisations seem almost magical in their ability to show, in a quasi-realistic visual language, something that does not exist. In their seamless mix of photorealistic elements, the work that has gone into making them entirely disappears.”

(Rose et al., 2016)

The future ghosts in the CGIs have a similar reflective function. You, the viewer scrolling or flicking past the image of the Garden Bridge, are suddenly transplanted from the room around you onto the Garden Bridge, inhabiting it in your imagination in a hyper-realistic re-location. In his theory of non-places, Marc Augé referred to this:

“As if the position of the spectator were the essence of the spectacle, as if basically the spectator in the position of a spectator were his own spectacle. A lot of tourism leaflets suggest this deflection, this reversal of gaze, by offering the would-be traveller advance images of curious or contemplative faces, solitary or in groups, gazing across infinite oceans, scanning ranges of snow-capped mountains or wondrous urban skylines: his own image in a word, his anticipated image, which speaks only about him but carries another name. The travellers’ space may thus be the archetype of non-place.”

(1995, p. 86)

PART 3:

PHANTASMAGORIA

PHANTASMAGORIA

AS IMAGE

Des Esseintes, the protagonist of Huysman’s 1884 novel A Rebours, is a sort of flâneur, the figure developed by Walter Benjamin to consider early nineteenth century Parisian streets, architectures and commodity cultures. Just as Benjamin’s flâneur might have done, des Esseintes escapes a downpour by ducking into an arcade, a glass-roofed, steel structured passage of shops between streets which had developed as a new architectural vernacular. Sitting in a bodega, he opened a guidebook to London.

“He settled down comfortably in this London of the imagination, happy to be indoors, and believing for a moment that the dismal hootings of the tugs by the bridge behind the Tuileries were coming from boats on the Thames.”

(Huysmans, p. 138)

It had been des Esseintes’ intent to travel to London, but instead he returned home, satisfied in the imagined experience of place the guidebook had led him to (Donald, 2003). The nineteenth century expansion of reproducible imagery, both visual and written, made a large impression on the distanced understanding ―and romanticisation of― place, much as when, earlier in the century, the scenic tourism industry had in part developed due to Gilpin’s writings on the picturesque. Rebecca Solnit (2001, p. 95) notes “a taste for landscape was a sign of refinement, and those wishing to become refined took instruction in landscape connoisseurship”. In this same vein, the reproducible form of imaginaries ―whether textual or, increasingly, visual― has a direct lineage to the CGIs we are being constantly subjected to today.

When Benjamin famously wrote “now a landscape, now a room”, he was alluding to the ability of the flâneur to read the urban as landscape, and to how the aura of various commodified objects and spaces was perceived by a gaze that could oscillate between a sense of the urban and crowd and that of the individual and domestic. He may have also had in mind the way in which detached views of nature and landscape were reproduced and for sale as prints alongside other objects for the home. One could purchase prints of picturesque views to curate a sense of self within the newly commodified domestic space.

Just as the picturesque had taken its name from landscapes that could look like the pictures of Claude Lorrain and other Grand Tour artists; the pictures on display in dealers’ windows, and the images in newspapers, included huge amounts of picturesque imagery (Green, 1990, p. 95).

“There were panoramas, dioramas, cosmoramas, diaphanoramas, navaloramas, pleoramas, fantoscopes, fantasma-parastases, phantasmagorical and fantasma-parastatic experiences, picturesque journeys in a room, georamas; optical picturesques, cineoramas, phanoramas, stereoramas, cycloramas, panorama dramatique.”

(Benjamin, 1999, p. 527)

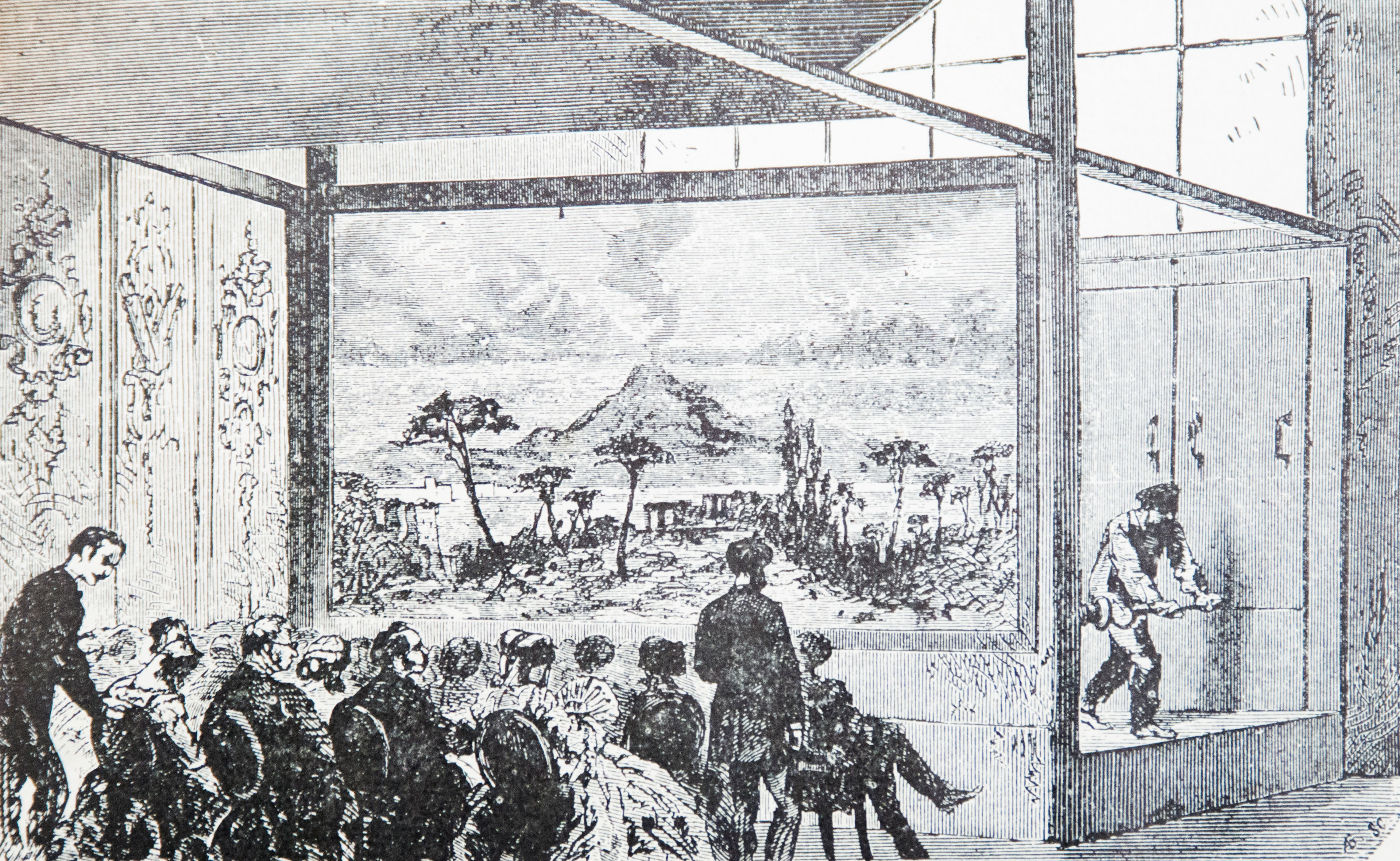

The experiences of nature, the sublime and picturesque were entering the urban not only via mechanically reproduced images, but also through experiential entertainments. The panorama was a vast painting hung in the round, in the middle of which visitors would sit on a raised platform and believe themselves to be inhabiting the scene surrounding them. Fashionable in France from the beginning of the nineteenth century, popular scenes were sublime and picturesque landscapes, and the sense of being in nature was now possible as an urban experience in a far more convincing and immersive way than printed and painted imagery had offered.

In 1822, Louis Daguerre developed the diorama, an evolution of the panorama featuring projected light-effects over the top of painted scenery to create a semi-real ―even a hyperreal― aura which was, in a spectacular way, more sublime than being in nature itself. By changing lighting techniques, colour, front and back lit projection, and using different sources of illumination, time could pass, streams could flow, or a drama could unfold (Arcades, p. 690).

The dioramic screen with worker behind and spectators in front, 1848 ©Dead Media Archive, 2010

The dioramic screen with worker behind and spectators in front, 1848 ©Dead Media Archive, 2010

In his writing on the picturesque, Uvedale Price spoke of the ‘glimmering’ he experienced in the paintings of Lorrain, “the playing lights, and colours, which often invert the summits of mountains” just as he had seen in “real nature” (1794, p. 154). This was the atmosphere that dioramas tried to recreate when they attempted to “bring the countryside into town” with a “perfect imitation of nature” (Benjamin, 2008, p. 99). For Benjamin, images were the key component in the phantasmagoria of capitalist progress, and through reproducible and persuasive imagery, the mythology of progress could take hold in popular consciousness (Stavrides, 2016, loc. 2802).

As one of the founding figures in the invention of photography, Daguerre was also responsible for the decline of the diorama as a popular attraction. He created the first photograph to ever record a human presence, a shoe-shiner and his client in an 1838 Paris street, who appeared in the image due to remaining in one place throughout the ten-minute exposure. Everybody else in it, whether walking or in carriages, disappeared as they moved too fast, and even the two who remained in the image appear as blurred ghosts, in what Benjamin refers to as “the earliest image of the encounter of machine and man” (1999, p. 678).

Daguerrotype of Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 3rd arrondisement ©Phaidon Press. London, 1997 [1838]

Daguerrotype of Boulevard du Temple, Paris, 3rd arrondisement ©Phaidon Press. London, 1997 [1838]

One day before the first Daguerre photos, or daguerreotypes, were revealed to the public, a journalist had a preview of them, to excitedly announce that soon, travellers would be able to buy a machine “to bring back to France… the most beautiful scenes of the world” (Gaucheraud, 1839). The most striking early images, however, were urban picturesques of Paris using an approach to pictorial representation that had been honed in painting; partly because it was easier not to have to carry the equipment and chemicals out into the field, but also because the colours of nature did not lend themselves to the emerging processes:

“Trees are very well represented; but their colour, as it seems, hinders the solar rays from producing their image as quickly as that of houses, and other objects of a different colour. This causes a difficulty for landscape, because there is a certain fixed point of perfection for trees, and another for all objects the colours of which are not green. The consequence is, that when the houses are finished, the trees are not, and when the trees are finished, the houses are too much so. Inanimate nature, architecture, are the triumph of the apparatus which M. Daguerre means to call after his own name—Daguerreotype.”

(Gaucheraud, 1839)

Panoramas, dioramas and photography were ongoing developments in the effort to conceive of a pictorial rendering that was more real than painting, but that still carried a sense of aura. Their direct predecessor was the phantasmagoria, a late eighteenth century magic lantern entertainment involving a glass-painted image of a figure, back projected onto a screen in a darkened room or glass pane. Accompanied by metaphysical speech or the sounds of a glass harmonica, the animated, movable images enlarge and get smaller, seem to float in the air, and ―to an audience who had not seen moving images before this spectral apparition― were magical and fascinating (Mannoni & Brewster, 1996).

PHANTASMAGORIA

AS EFFECT

In Capital, Marx discussed commodity fetishism by employing the German “dies phantasmagorische form”, translated into English as “fantastic”, which misses out on the subtleties of Marx’s understanding of the aura of seduction the phantasmagoria shows exuded (Gunning, 2004).

“There, the existence of the things [between] commodities, and the value relation between the products of labour which stamps them as commodities, have absolutely no connection with their physical properties and with the material relations arising therefrom. There is a definite social relation between men, that assumes, in their eyes, the fantastic form of a relation between things… This I call the Fetishism which attaches itself to the products of labour, so soon as they are produced as commodities, and which is therefore inseparable from the production of commodities.”

(Marx, 2013, p. 47)

His thoughts on the aura of commodified objects ―and people, relating to one another― was further developed by Benjamin who, thinking more upon the magic lanterns and dioramas, also considered the very apparatus of their projection into the world, as well as the expansion of the idea of them into whole architectures, landscapes, experiences and dreams of transcendence (Murphy, 2016, loc. 3353; Blaettler, p40). For Benjamin, phantasmagoria was an aura which transformed the individual, or the citizen, into a consumer through their relationship to objects or to a place which has its own aura related to a use-value superseding any function.

As Graeme Gilloch states, “the metropolis is the principal site of the phantasmagoria” (1996, p. 11) in that it aids in the creation of the modern myths of urban life. And if the city can be thought of as the ultimate monument to the subjugation of nature by humankind, then the Garden Bridge can be considered as a icon of this colonial control and commodification of nature, serving a higher capital function.

PHANTASMAGORIA

AND THE ARCADES

Gilloch remarks that commodity fetishism doesn’t just derive from the singular objects for sale behind the arcades, but from the experience of the modern city itself. “The arcades, the boutiques and the department stores are shrines to the commodity; they are its temples, where one goes to pay homage” (1196, p. 119). From this array of commodities, the new consumer could choose those which best suited their self-perception to decorate the:

“phantasmagoria of the interior, which are constituted by man’s imperious need to leave the imprint of his private individual existence on the rooms he inhabits.”

(Benjamin, 1999, p. 14)

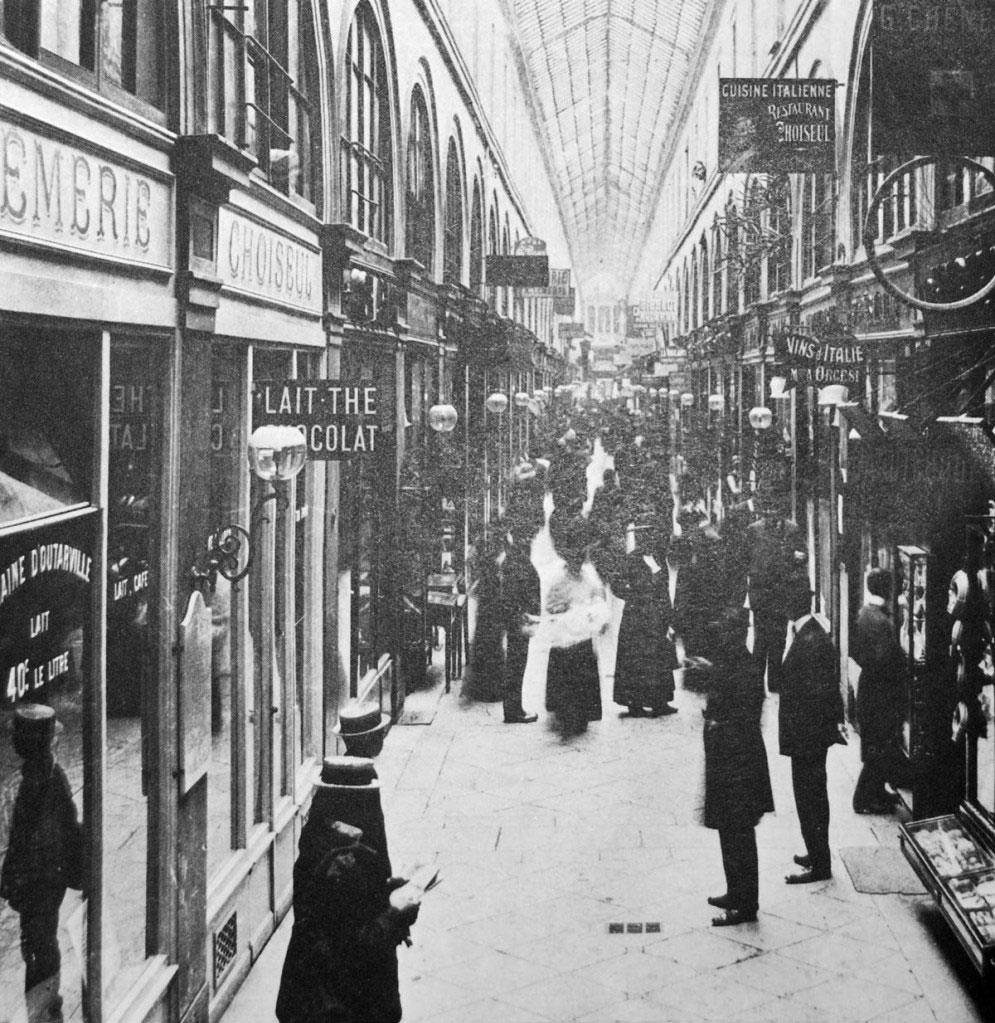

Passage Choiseul copyright unknown

The Paris of this period was, for Benjamin, a city composed of mirrors and glass (Mertens, 1996). The bistros glowed due to their mirrored and glazed surfaces, resulting in a city offering spaces where “women … look at themselves more than elsewhere”, and even the “asphalt of its roadways is as smooth as glass”, with the gazes of passing strangers as “veiled mirrors” (1999, p. 537).

Glass operated two-fold in the consumer palaces of the arcades: as the barrier between the individual and the fetishised product on display ―keeping it simultaneously immediate and at bay― and as the material in which these products were frequently made. Benjamin remarks on Apollinaire’s observations of “shoes in Venetian glass and hats in Baccarat crystal” (1999, p. 19). The glass cases in the shops contained aspirational products of the latest fashion which crystal lamps illuminated from above. On a more macro level, the arcade also acted as a social vitrine, with the precious commodities being the consumers themselves.

PHANTASMAGORIA

AND THE GREAT EXHIBITION

“World exhibitions glorify the exchange value of the commodity. They create a framework in which its use value recedes into the background. They open a phantasmagoria which a person enters in order to be distracted. The entertainment industry makes this easier by elevating the person to the level of the commodity. He surrenders to its martipulations while enjoying his alienation from himself and others.”

(Benjamin, 1999, p. 7)

The steel and glass used as the modern materials to frame the phantasmagoric products in the arcades were pushed as a vernacular no more than in plant houses, such as Joseph Paxton’s at Chatsworth and Kew. These heated spaces could house exotic blooms collected from all over the world and display the wealth and power they implied to guests. When Paxton was invited to replicate his spectacular architecture as a palace of consumerism for the Great Exhibition of 1851 among the elms of Hyde Park ―a row of which the construction encased― it was instantly well received as a juxtaposition of contemporary design and nature (Benjamin, 1999, p. 158). In this space, the intermingling of industrial objects, plastic arts and exotic nature became a montage to create a site of overwhelming phantasmagoria:

“Lightly plumed palms from the tropics mingled with the leafy crowns of the five-hundred-year-old elms; and within this enchanted forest the decorators arranged masterpieces of plastic art, statuary, large bronzes, and specimens of other artworks.”

(Benjamin, 1999, p. 184)

McNeven, J. and W. Simpson. “The transept from the Grand Entrance, Souvenir of the Great Exhibition” ©V&A Museum, 1851

McNeven, J. and W. Simpson. “The transept from the Grand Entrance, Souvenir of the Great Exhibition” ©V&A Museum, 1851

Understanding the power of nostalgia, Boris Johnson flirted with the idea of allowing a Chinese developer to recreate a simulacrum of the Crystal Palace on the south London site the original was relocated to before its end in flames in 1936. Conversations had been going on since 2011 to create a version of “in the spirit” of the palace, housing a 6-star hotel, jewellery showrooms and art galleries, with local planners approving plans claiming it would support London’s World City role. By late 2014, the project was called off amid wide consideration the Chinese developer was simply using the Great Exhibition’s aura to get their hands, cheaply, on a prime public park in advance of more aggressive development (Murphy, 2017, pp. 93-119). Johnson’s other project from this period, however, was slowly progressing, and it could even be argued that the Garden Bridge was closer to the original Crystal Palace than any interpretation of it on its former site could have been.

For Benjamin, phantasmagoria had a useful function for elites. As the “political concept of equality was displaced onto the realm of things” (Buck-Morss, 1983, p. 231), the citizen became a consumer, and the fear of revolution was subdued by the intoxicating promise of commodity abundance. Johnson took on the proposition of the Garden Bridge one year after the 2011 London riots, brought about through urban inequality, social exclusion and government cuts just as the Great Exhibition had been launched amid increasing political unease. Rooted in nostalgia, it is possible that Johnson saw in the Garden Bridge his own legacy of future, nature and spectacle combined, which would, as the Great Exhibition had in its time, spread around the world in mediated form and ennoble London’s World City status.

PHANTASMAGORIA

AND THE GARDEN BRIDGE

If Benjamin thought World Exhibitions were spaces of pilgrimage for the commodity fetish, one can only wonder what he would have made of the Garden Bridge. He would have instantly grasped the phantasmagoria imbued in the GBT’s imagery (Benjamin, 1999, p. 804). Indeed, he may have read the Bridge as a neo-Haussmannisation, in the sense that public open space was being enclosed by a private development, while public views from Waterloo Bridge would be “re-located”.

Just as, to Benjamin, Haussmann’s boulevards, imposed into the dense fabric of Paris, were meant to ease passage for the military between barracks and workers’ districts to retain imperial Napoleonic power (1999, p. 12), so too the Garden Bridge would have served neoliberal and capital power by depoliticising space amidst the phantasmagoria of a brand-new world of promises and ecological progress (Stavrides, 2016, loc. 1786). As a tool for “strategic embellishment” (ibid.), it would have acted as a device of passive respect to the financial state, using nature as a shock absorber and an instrument to funnel 7 million tourists from the popular Southbank to the north side of the Thames, where new developments would have benefited hugely in financial uplift from both footfall and iconic aura.

Passages and bridges act as thresholds between distinct other spaces, symbolising and reifying the act of connection (Stavrides, 2016, loc. 949). This was an image the GBT wished to project, though theirs was an enclosure project limiting the hours and days in which the public could have access to it. Its function as a threshold was entirely atmospheric. This was a private space designed to appear public, a programmed space made to look free, an enclosure phrased as a threshold, a space with heavily commodified function presented as a gift for pleasure and relaxation.

In this sense, was a neo-arcade. The arcade and the Crystal Palace alike appealed to contemporary architectural approaches to enclose spatial functions by offering spaces for commodity fetishism in which precious objects ―the space itself, as well as the self and one another― were imbued with a phantasmagoric aura. It wasn’t just the moneyed bourgeoisie that could partake of the arcades or the fair; those who couldn’t afford to buy could still window shop, dreaming of interiors decorated with the objects on display. The Garden Bridge replaces glazing with projected (and perceived) openness, though barriers and regulation still control the space. It replaces the aesthetic of nature with actual nature, though this nature is mediated, managed and a tool of the phantasmagoric experience.

The objects that were neatly arranged in the vitrines of the arcade shops have been replaced with the neoliberal London City cluster. Visitors to the Garden bridge would have passively gazed out into the most spectacular, phantasmagoric objects that we have, the forms and icons of the commodified skyline. The architectures of the Gherkin, St. Paul’s, Lloyd’s, the Walkie Talkie and their brethren would have been transformed into immediate, yet remote, objects of awe; framed by nature, the contemporary architectural equivalent of the arcade. Perhaps, we would have stopped on the bridge to take a selfie toward the city, compressing our self into the commodified aura, much as a visitor to the arcade would have had their own face reflected back at them as they peered through the glass.