Free Time & the City Symphony

The BarbicanTalk

2021

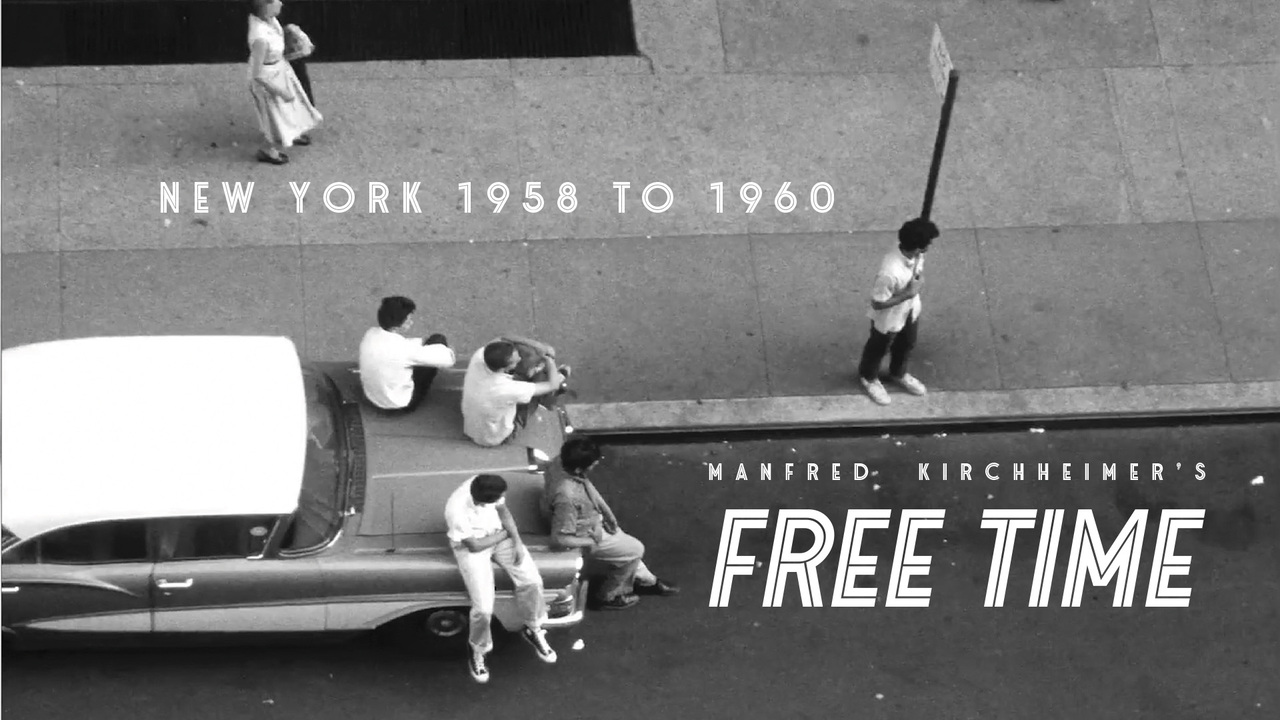

I was invited to give an introduction to a screening of Free Time, a film Manfred Kirchheimer shown at The Barbican for their first film back after Covid lockdown. The film is a montage of 16mm footage Kirchheimer shot in New York from 1958 to 1960, but which then remained unused until he revisited it to form this edit in 2020.

The text below is a transctiption of my introduction, and you can watch the film online HERE.

About half-way through “Free Time”, we will see a man – presumably homeless – wheeling a cart laden with cardboard, books, cloth and assorted materials. As we watch him in profile push across the screen, our sightline gets interrupted as he is overtaken by a van, bearing the words “Art Movers” on the side.

The van passes by, and he then continues on his journey. we don’t know where he is headed, but it is sincere and evidently a struggle. We see that struggle from various angles – at eye level, from high up looking down through an architectural ravine, then close up as one of the items falls off and he has to rearrange and restructure his hoard.

It is then we notice that it is not the same man who we saw overtaken by the art mover van, and we realise that as we have been following this montage of him pushing his collection through the streets, we have in fact been witnessing a number of New Yorkers, and not one man on a single journey.

This helps us understand what a City Symphony is. Where all the human actors – citizens in the act of various citizenships – are simply non-speaking extra walk on parts in the (literal) shadows of the primary protagonist, urban place. The camera regularly follows people going about their daily lives, as Manfred Kirchheimer does so in the film you’re about to see.

For a moment we see their situation, live their life, and then we get handed over to another character, a living prop by which we experience place, architecture, and interaction. We observe from a distance, even when the camera pulls close.

The first photograph taken was taken by Joseph Niépce nearly 200 years ago. Through an unfocused haze, he captured rooftops in Burgundy. Ever since, the city, urban, built landscape has been central to photography - the slow exposure times that analogue processes demanded suited subjects which didn’t move. When technology developed, and the still became moving image, the urban remained in focus.

Some of the earliest popular films were simple documentary footage of cities: “Eine Fahrt Durch Berlin” 1910; “Marvellous Melbourne” and “A Trip through New York” from 1911; and “Ottawa: The Edinburgh of the North” 1919. These could be toured around, bringing distant worlds into local village halls or community centres with a never experienced, mind-blowing reality. They were simultaneously travelogues, place-marketing, and creative exercises. All ingredients which often feed into the City Symphony genre.

It is, however a genre which in some ways defies definition, and some may argue that “Free Time” isn’t a City Symphony at all (though my personal definitions are pretty loose). They can fold in photojournalism, politics, the abstract and experimental, technological experimentation, documentary, ethnography, and marketing.

They frequently, but not always, follow the simple passage of a day - sunrise to set, waking to sleeping, empty to crowded to empty - and tend to be non-narrative in form. But for every key ingredient, there’s a classic contradiction - some deny that Vertov’s 1929 “Man with a Movie Camera” can be classed as a City Symphony because it has too much narrative.

One misconception is, however, that a symphonic sound score is required. While often set to music – including sometimes setting older films to contemporary scores such as Jeff Mill’s wonderful electronic score to Walter Ruttmann’s 1927 “Berlin: Symphony of a Great City” – the “symphony” referenced is that of the city, the elements combining in controlled cacophony. This touches on a critical aspect of what makes a city film a City Symphony - the artistic eye, an awareness of the poetic. This is perhaps literally spelled out on the side of the overtaking van mentioned earlier - “Art Movers”.

One hundred years ago this year, the painter-interested-in-photography Charles Sheeler and photographer-interested-in-film Paul Strand collaborated on a silent short film comprising 65 shots set to poetic phrases by Walt Whitman, ten minutes montaging of an early 20th century Manhattan in the process of rising above the Hudson. The city is abstracted, cut up into unexpected geometry, and architecture is photographed from great height looking down or from the street towards the peaks – both directions equally inducing vertigo.

Industrial smoke rises from ships and trains funnels and is expelled from brick warehouse chimneys, while modern steam vents from the roofs of skyscrapers. People in the main are distant, shot from afar and made miniscule by the bravado of the new architectures, or collected as swarms, channelled into streams.

“Manhatta” is considered to be the first – or at least a foundational moment – in the genre of the City Symphonies, and it is informative that it was a product not of traditional film-makers but from visual artists who used film – the idea of film’s relentless strobe of still photographs as a power to be an independent art form not beholden to narrative, and which uses the same tools of visual art with added duration.

Photographer, painter and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy never made a City Symphony, but he planned one in the 1920s. Titled “Dynamic of the Metropolis”, it exists as a graphical visual screenplay, a cutup structured storyboard. Alongside, he wrote:

“The intention of the film “Dynamic of

the Metropolis” is not to teach, nor to moralise, nor to tell a story; its

effect is meant to be visual, purely visual. The elements of the visual have

not in this film an absolute logical connection with one another; their

photographic, visual relationships, nevertheless, make them knit together into

a vital association of events in space and time and bring the viewer actively

into the dynamic of the city.”

City Symphonies sit on the thresholds which so often concern urban and architectural thinking, and where artists are so often most nourished- Public><Private, Inside><Outside, Man><Machine. This film, Free Time, exemplifies that.

There is a puncturing of the literal threshold between domestic and public - a man coming out of his house and down his steps into the street, a boy precariously crouching in an open window cleaning the outside of the glass, the sprung metalwork of a mattress being taken out of a flat whilst a group of neighbours sit in the adjoining steps, talking.

It’s a bit cliché to go to the writing of Walter Benjamin when discussing urban cultural issues, but in respect of City Symphonies it is worth diving into the Arcades Project, his fragmented collection of ideas, observations, poetic resonances, repetitions - and even cul de sacs - that is itself a highly-visual montage of all things urban and archive. He wrote:

“Couldn’t an exciting film be made

from the map of Paris? From the unfolding of its various aspects in temporal

succession? From the compression of a centuries long movement of streets,

boulevards, arcades, and squares into the space of half an hour? And does the

Flaneur do anything different?”

His flaneur – the sauntering stroller conjured from the writings of Charles Baudelaire – is ever-present in City Symphonies. The character that observes the thresholds while simultaneously being one themselves – the threshold between observer and observed, between translation and audience, between lived and represented experience.

He is a gatekeeper of how the city is perceived and read, and is the author of cultural urban narratives from word to image to film. He is also always a he, white, and a silent voyeur. Which is not to delegitimise any vantage or viewpoint from these flaneurs, psychogeographers, directors or photographers, but to always question the privilege which is present within being able to hold such a position of being that threshold, and to be aware of those who do not have that power even if subject of its gaze.

One hundred years later, we in an age where we do not need to go to the village hall to see a touring projectionist present a distant place to us. We can immerse ourselves in Imax, load up a computer game to freely explore (and explode) highly accurate digital simulacra of cities, or render architecture in such hyper-realism before it’s built that when the building is finished it only disappoints the client for not having such a glowing aura.

And is there a delayed poetry between the New York we will see in “Free Time” and a 21st century London? You will see kids chalking out games onto the road, a sense of civic ownership which has returned in the pandemic as cars are shut out.

And here, in the centre of a London constructed from relentless cycles of demolition and reconstruction, perhaps we see resonance with Kircheimer’s imagary shot through building site fires, flames which while black and white still conjure a threatening aura and heat haze through which he renders the city in transition beyond. In the film you will see smashed up shop fronts and glazing with ominous white crosses on, primed for destruction, and here we sit in a city where developers and councils work together to dispossess, demolish and rapidly reshape history and communities.

So what power can a City Symphony have, and what could it look like, in our digital landscape of decolonisation? With calls for feminist and child-centred play-friendly cities who would be the observer, who the observed, and what power dynamics are at play?

This film is a digitised 21st century assemblage formed from 45,000 feet of mid 20th century analogue 16mm footage, overlayed by a highly polished modern sound edit. It is is perhaps a good starting point to think about some of the questions around past, present and future. How did the city look in the 1950s? What citizenship and agency is present in this film which is not present now, or visa versa? Who are we behind the lens, who are we watching now, how does our presence – silent or active – in our ongoing city symphony inform the place we inhabit? Who writes the stories, who watches them, and who is subject within them?