Disposed totems: Thoughts from the foreshore

Essay2019

An essay accompanying my visual art projects Disposed totems & A series of organised objects, which you can see HERE.

It takes two steps to leave the centre of London and enter a new territory. But it requires a kind of bravery, to trust oneself to step outside the ordered control, tarmac and concrete of the managed Thames path, and to displace your body into the anarchic zone of the river’s foreshore.

It feels like trespassing, these are alien spaces and unwelcoming to those not yet familiar. But it does not take long striding over the riverside beaches and debris to feel a sense of homeliness, relaxed in the calm, quiet and solitude despite being at the epicentre of 8 million people. This is, after all, public space. Little advertised, but perhaps the last freely accessible wilderness in a city increasingly commodified, caged and controlled for capital and ‘safety’.

There are few opportunities in the developed city to feel a sense of the wild, of raw territory. The parks are programmed, manicured and secured. Surveillance surrounds, and modes of behaviour are deeply coded into how we feel we should act, behave and be in the modern metropolis.

Save for parts of Epping Forest and perhaps moments of South London’s commons off the beaten track, the urban experience is one entirely expected, and at every step designed, organised and shaped with consumption in mind. But on the foreshore there is sense of the primeval, anarchy and disorder. It is a temporary space, and this sense of it appearing and then getting taken away feeds into the unique atmosphere conjured up.

These spaces are never the same twice. Just as the water rushing in and out and side to side seems as a constant over the centuries yet is a in reality slippery serpent of constant change, so too is the beach of detritus and material that it has sucked up over our time alongside it.

It conceals our past, and the objects that we consider waste. Shopping trolleys, tiles, animal bones, bricks, fragments of the everyday and the everyman. It takes it all, hides it from view, then when least expected throws it back to be discovered by whoever happens to walk the shore and glance down.

In the 1800s these people were mudlarkers. Women and children who waited by the Thames steps for the waters to descend, before racing one another into knee-deep mud to hunt for pieces of metal and coal lost overboard, making pennies from assorted finds.

The mudlarkers of today are curious amateur archaeologists and historians, discovering fragments of delftware, handles of pots, clay pipe stems and clues towards those who went before. Occasionally grander finds turn up. Roman coins, Byzantine jewellery, ancient weapons. But it’s rare to find anything whole, even asbestos tiles and bits of buildings demolished over the last few decades of riverside gentrification now turn up as parts of a whole, fragments and extracts of a vision of the time.

THORNE

Sites of power and surveillance watch over, as waves reveal and conceal in their own time — duration and sediment muddy what we once knew. The past’s disposed bide in the dark, a growing collective power underneath, out of sight. The forgotten return, together.

At the central beaches, on the South Bank in particular, the edge feels welcoming, inviting even. Secure steps lead down to a sandy shoreline, and promenaders walking the promenade look over and down onto sand sculptors, hunting children and curious tourists.

But other beaches are less popular. Some are harder to get to. Gates from the footpath can be locked, or access is only through an unwelcoming alley. Some are covered in slippery algae or with treads missing, seemingly dissuading you from daring to pass.

Then there is the risk, the fear that the waters can rise and swallow and submerge you, just as they have concealed all the flotsum, jetsum, bones and bricks of the past beneath. You fear that the tide will return at an unexpected pace, before you can reach the steps that led you from the security of the street, and that your bones will one day collect with the cows, boars, sheep and beasts of the watery ossuary.

The waves gently washing the edge provide a sonic shift from the normal urban sounds. A mix of water and percussion as energy transfers from liquid to solid, dragging bits in and pulling pieces back. Each collision of object to object wearing each down a little more, softening right angles. You may sometimes hear snatches of commentary from a passing tourist boat.

You will only hear short sections of the stories that the guide is imparting to passengers. Faces on the cruise-boat look in your direction, but you are at such a distance that you can’t tell if they are looking at the city above and beyond you, or if they have noticed you, solitary stalker of the zone between land and water. You wonder what they wonder if they see you.

You may occasionally see another beachcomber, looking down in scattered concentration. You may share a greeting, but each remains alone, for the beach is a space of solitude. Just you and the millions of stories underfoot, fragments of lives, of places, meals, everyday detritus of every day of London’s past.

GABRIEL

From industry to spectacle, as places change fragments of the old linger — valued remains preserved as monuments to another time, the difficult and unexploitable abandoned to water. Awkward detritus litters the zone, the river unable to break down instead hides it from view. Tourists gaze in search of singular meaning, as complicated histories return to the shore.

The Thames is more than a river, it is a shorthand symbol to so much of what we consider to be English, or British, or Londonish. A lazy shorthand, for those who think the complexities of such things are simple enough to be encapsulated by a water path. And symbols are so easily exploited, by political ideologies or those who want to latch their ideas onto somebody else’s meaning.

Property developers do this. Speculative apartments receive an instant uplift of millions once advertised with a Thames view. Those who buy may well never set foot in their investment opportunity, instead those views could remain unseen as owners wait to flip, for invisible capital to inflate. Views over, and land abutting, what is perceived to be our national river, private profit from collective wealth.

But the foreshore is truly public. And the views, the views, so wide and flat and so close to the glistening reflection. From ground level you are at one with these vantages, the waters and the histories they conceal. From your luxury penthouse you are imagined owner of them, looking down with a passive gaze. From the shore you are one. Standing amongst the bones, bricks and collected objects from our collected past.

This is arguably London, more than the mediated views of office blocks and the touristic gaze of Buck House and polished architectural wholes. This is London, the detritus and crap that London left behind, because you, and me, all of us are the detritus of current London, we the disposed, the worthless and undervalued, we are at one with our kin on the beach. London.

TRIG

At the edgeland where city pushes periphery, compressing capital to river. This is the realm things go when no longer an asset. Bearing scars of extracted value, the disposed return as strata with new power, lining up against systemic forces, organising.

Artists have used the river before. Richard Long extracts mud from the Avon, his national river, and plasters it across gallery walls. Bosco Sodi creates perfect circles of cracked, aged, deep and ruptured mud. And Mark Dion scoured the Thames beaches in front of both Tate galleries for fragments, archaeologically cleaning, categorising and displaying in Victorian vitrines.

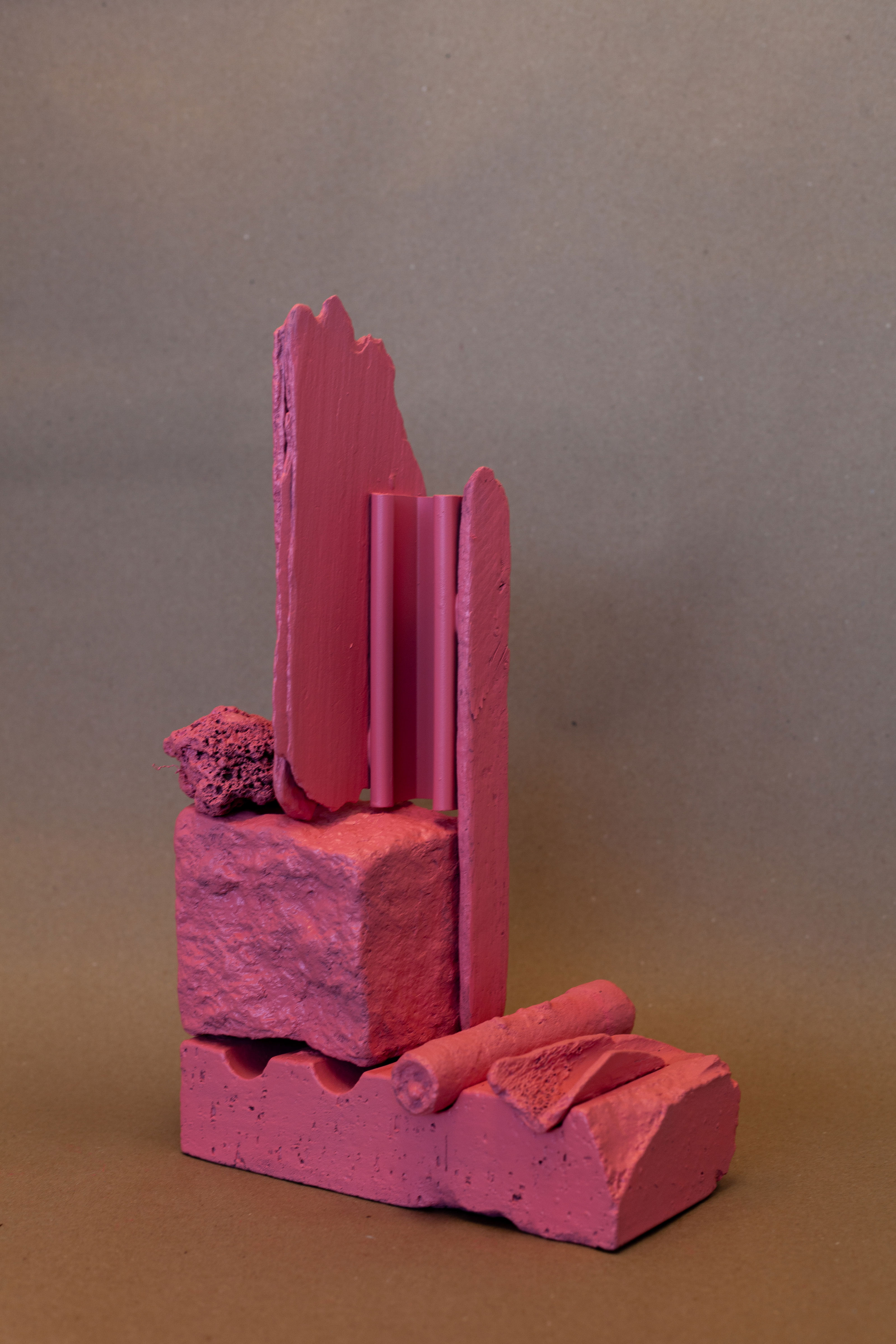

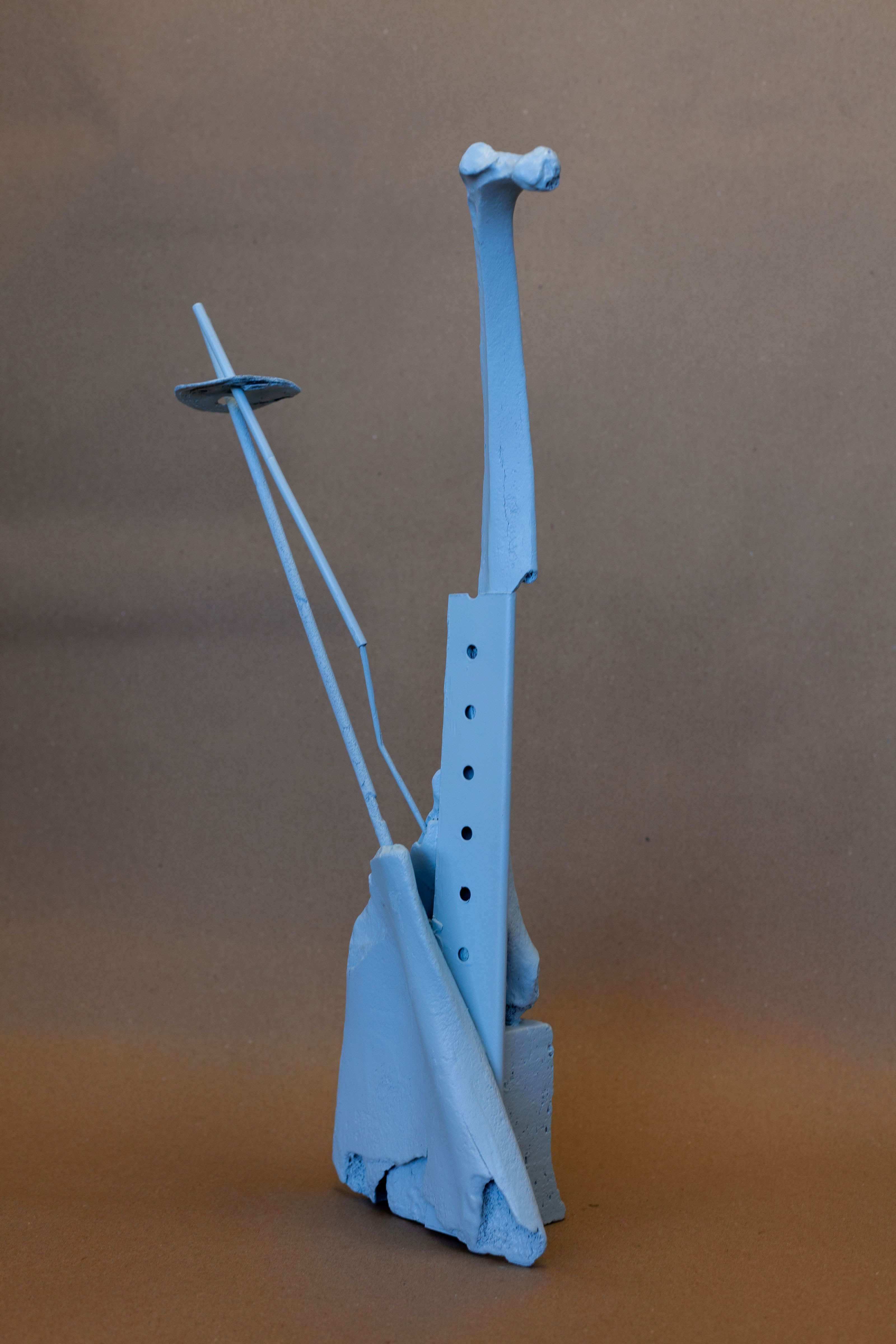

I have reconstructed fragments as totems. Four totems, taking linguistic cues from the olde London names given to the steps that descend from city to shore, and taking colour cues from details of the colours used in the speculative neoliberal developments which aggressively push up against.

The totems help to coalesce forces, as well as objects. Forces that summon up energies of all that was once disposed, that from which all capital had been extracted, that which no longer had purpose in someone else’s grand plan. Here, rescued and restored, they return and stick a metaphorical finger up at the developments that succeed them. They are me, and you, they are us and all who feel part of the beach.

RATCLIFF

Spaces shaped around physical exchange retain residue from friction and fallout. Where once immense action and noise, now silence and calm. Above, transactions continue, now invisible and silent. Below, the dirt and grit of the past, an obstacle presumed overcome by those unaware it was subsumed, not removed.

Other items self organise. Boar’s jaw conjoins with scaffold knuckle. Slates squeeze up to shell. Shins, shoulders, unknown parts of unknown beasts find friendship with unknown parts of buildings and the fabric we built before. As if they joined together in the darkness of the depths, waiting to come to the surface and, together, provide a voice which was once lost. Voices that would not be drowned.

The bones are everywhere, adorned with scratch marks which illustrate the force of value extraction. They line up on the beach, soldiers facing action. As you walk over them you loose focus, there are so many. They become indistinguishable from one another. Maybe they aren’t even animals, you wonder. Londoners?